Interdiction for the Protection of Children

By Michael L. Yoder, M.A., M.A., and Wayne R. Koka

The Texas Department of Public Safety (TXDPS) has pioneered an innovative training course, Interdiction for the Protection of Children (IPC), to help troopers identify and rescue endangered children. The idea for IPC developed in 2007 during conversations between representatives from TXDPS’ Education, Training, and Research Division (ETR) and Texas Missing Persons Clearinghouse (TMPC) who envisioned the need for a new course to teach troopers how to observe suspicious behaviors associated with missing children and child abduction offenses. While TXDPS troopers were well-trained and highly proficient in making observations of suspicious behaviors leading to arrests and successful interdictions of illicit drugs, weapons, and currency, they lacked training and experience in working child victimization cases.

The need for an IPC program became evident in 2008 when 57,742 children were reported missing in Texas, while a TXDPS database that collects trooper activity records reflected no recoveries of missing children.1 The absence of child recoveries was astonishing given that TXDPS troopers conducted 2,891,441 traffic stops the same year that resulted in numerous criminal arrests and contraband seizures.

Part of the issue involved the database, which lacked programming data fields to collect child recovery information. Another problem involved the field interview card (FIC) used by troopers to report observations of suspicious activities to the TXDPS’ Texas Fusion Center (TFC) for intelligence and investigative analysis purposes. The FIC had no data fields for troopers to record suspicious activities involving children, and the TFC database lacked the means to collect, analyze, and statistically report such data.

As a result TXDPS could not accurately identify the nature, extent, and trends of child victimization and child recoveries. There was no way to know how many of the nearly 58,000 missing children may have been abducted. Conceivably, TXDPS troopers could have observed abduction victims and offenders, but the troopers lacked training in recognizing abduction indicators and, thus, took no effective police actions. It became evident that TXDPS needed to revise the FICs and the TFC database, as well as train its patrol personnel on the techniques and indicators for identifying suspicious behaviors associated with child abductions and missing child cases. These factors led to the birth of the Texas IPC program concept.

THE PROGRAM

A volunteer group of commissioned and noncommissioned TXDPS members tackled the project. The development of the IPC program is based on a three-tiered, integrated approach to identify children at risk during law enforcement encounters. The tiers focus on 1) law enforcement officer training, 2) revision of reporting and intelligence-gathering methods, and 3) officer expertise.

Special Agent Yoder serves in the FBI’s National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, Behavioral Analysis Unit-4, Crimes Against Adult Victims.

Mr. Koka is a major case specialist in the FBI’s National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, Behavioral Analysis Unit-3, Crimes Against Children.

To move the program forward, TXDPS hoped it could include elements of other law enforcement agencies’ child abduction training programs in the curriculum. In June 2008 a nationwide search commenced for courses designed to teach patrol officers about child abductors and how to observe their suspicious behaviors during encounters. However, no applicable program was found.

The many contacts made by TXDPS included the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit-3 (BAU-3), within the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime (NCAVC) in Quantico, Virginia. BAU-3 assists local, state, federal, and international law enforcement agencies in violent crime investigations regarding child victimization. It conducts research, provides training to law enforcement personnel, and offers operational assistance to police agencies conducting investigations of both active and cold cases. The unit specializes in child victimization matters, including missing children, child abductions, mysterious disappearances, homicides, serial murders of children, and child sexual exploitation (e.g., molestation, prostitution, pornography, and Internet-related sexual exploitation).

Training

In its desire to provide patrol officers with child abduction-related training, TXDPS built the IPC program upon the troopers’ established adeptness and experience in making observations of suspicious behaviors during interdictions for illicit drug, weapon, and currency crimes. Impressed with this original and innovative proposal, BAU-3 believed that, most important, the IPC concept had tremendous potential that could expand to other areas.

Abductions of prepubescent and pubescent children fall into two general categories: 1) sexually motivated and 2) nonsexually motivated offenses. Beyond the stereotyped and highly publicized abductions of children by strangers, several other forms of child abduction exist, including abductions by acquaintances, infant abductions by strangers, ransom kidnappings, and—the most prevalent kind—parental/familial abductions. Each type of child abduction can be committed by criminal offenders who may display distinctive traits, motivations, modus operandi, and behaviors that differ from offenders who commit other types of child abductions. Not all child abductors or abductions are alike. One of the authors suggested the IPC training should provide instructions on every known form of child abduction offense and every type of child abductor.2

The author further said that child abductions are just the “tip of the iceberg” among a much-larger range of child endangerment risks. He suggested that the IPC training curriculum should cover every child endangerment situation patrol officers could encounter, including physical abuse and neglect, sexual assault, sexual molestation, Internet sexual exploitation, dangers posed by sex travelers, grooming methods, child pornography, and child trafficking. He explained that incidents of missing, runaway, and “throwaway” children also should be included because of the large number of occurrences coupled with their increased risks for criminal victimization and other perils.

A comprehensive training course covering all of these topics was preferable, particularly for patrol personnel and other first responders, given the transient tendencies of many missing, runaway, and throwaway children and criminal offenders. Comprehensive training would substantially enhance the officers’ awareness and their understanding of multiple child endangerments, as well as the broad range of offender and victim behaviors. Officers who underwent inclusive training would be far better prepared to make observations of suspicious activities and conduct proactive interdictions relative to a variety of child endangerments.

Recognizing the practicality and benefit of IPC training, the author offered BAU-3’s assistance in helping TXDPS design and develop its IPC training course. What initially began as a focused objective to train troopers about missing children and stranger abductions quickly forged a strong partnership between TXDPS and the FBI to make IPC a premier training course for patrol personnel on the subjects of child victimization offenses and risks. IPC training educates patrol officers better to identify child endangerment situations, at-risk children, and criminal offenders who target children so that appropriate actions can be taken.

The curriculum capitalizes on TXDPS’ established drug interdiction training and its experienced and knowledgeable troopers, who are adept at observing suspicious behaviors connected with drug trafficking and other criminal activity. The IPC course features BAU-3’s extensive research and operational experience dealing with risk assessment, child victimization, and the variety of criminal offenders who prey upon children. BAU-3’s knowledge of the typical motivations and modus operandi and the personality traits, characteristics, preferences, and behaviors of each type of child offender (as well as the similar attributes and vulnerabilities of the targeted child victims) represent essential elements of the IPC training course.

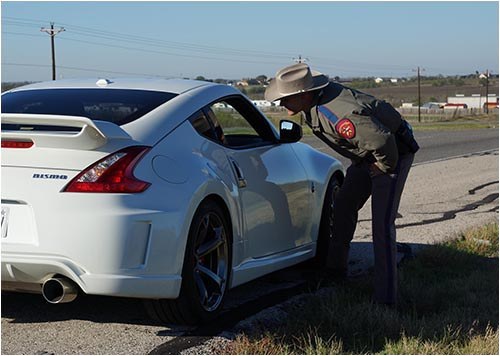

Akin to TXDPS’ drug interdiction training, the IPC course covers legality issues and techniques for scrutinizing suspicious behaviors and actions before and during police encounters. Troopers learn observations to make and appropriate questions to ask children and adults. Effective communication approaches tailored to a child’s age, development, and culture (e.g. effectively communicating with a silent, fearful 4-year-old vs. a brash, hostile 16-year-old) form an integral part of the training. Troopers learn useful preliminary investigation techniques; methods to identify child pornography, child erotica, and other evidence and where it may be found; intelligence gathering methods; and proper reporting procedures.

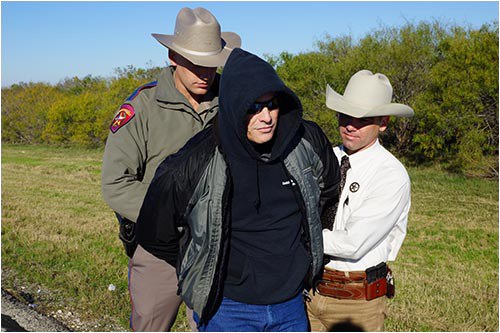

Interdictions involving children can be challenging and potentially volatile; the IPC course teaches patrol officers how to defuse emotional situations and gain cooperation. Officers receive instruction on field interviewing techniques for children and adults. The course emphasizes a litany of available resources patrol officers can access, including criminal investigators, child forensic interviewers, child and family social services, medical and mental health professionals, child interview specialists, legal experts, and BAU-3 members.

Upon completion of the curriculum development, a 3-day pilot IPC course was conducted in September 2009 at the TXDPS Training Academy located in Austin. The pilot course attendees included a select group of TXDPS supervisors, patrol troopers, and training instructors; invited Texas law enforcement personnel from several major municipal and county jurisdictions; and representatives from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Instructors represented TXDPS, the Texas Attorney General’s Office, U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, and BAU-3.

Attendees reviewed the training’s quality and comprehensiveness. Many individuals expressed that they did not know the magnitude, multiplicity, and degree of child endangerments. Several acknowledged that they had encountered suspicious adults and children during traffic stops and felt something was amiss, but could not fully identify the problem. Regrettably, they released the adults and children. “When I was a trooper, I became really good at looking for clues when it came to drugs, but I didn’t see the signs of at-risk kids. As I look back, there were probably several times that a kid was in trouble, and I didn’t do anything. My gut told me there was something wrong, but I didn’t get it.”3

The success of the pilot course demonstrated the value of and need for IPC training. As a result TXDPS instituted IPC training among its mandatory in-service training courses for all troopers, investigators, and Texas Rangers. TXDPS also provides IPC training to police officers and sheriff’s deputies across Texas. To date TXDPS has trained over 2,900 Texas law enforcement officers.

In October 2014 the Texas Department of Public Safety received a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice, Community Oriented Policing Services, in the amount of $95,495 for its Interdiction for the Protection of Children program. The agency will use the money to conduct 10 train-the-trainer courses across the United States.

Reporting and Intelligence Gathering

With the IPC course’s successful implementation, TXDPS concentrated on achieving the second tier of its integrative approach to identify at-risk children through revision of its reporting and intelligence-gathering methods. TXDPS recognized the need to revise its FICs, but did not know exactly what information was essential. Upon TXDPS’ request BAU-3 members suggested revisions to the FIC’s data fields that the agency subsequently adopted. Today troopers use the revised FICs to report observations of actual or suspected child crimes. Once completed the FICs are submitted to TFC for entry into its database, analysis, and necessary follow-up actions.

Similarly, a modification of the TFC database allows for the collection and analysis of the inflow of raw intelligence and child victim and offender information. TFC established an IPC information repository that serves as a resource for all law enforcement and victim services agencies within the United States. TFC currently collects intelligence information provided by patrol personnel regarding high-risk children and criminal suspects and provides this information to a variety of investigators. TXDPS integrated its 24-hour communications system with the IPC concept and created a missing/exploited child recovery teletype to track rescues of children and to integrate various units within TXDPS to assist victims and their families, provide additional investigative resources, and communicate information to outside agencies.

As a result of these second-tier revisions, troopers now can submit and receive information related to adult subjects and children who previously have been stopped. The changes TXDPS made to collect intelligence data relative to high-risk threats to children brought to light by patrol interdictions have proven innovative. The gathered intelligence serves as a valuable resource to first-line troopers and officers engaged in patrol inquiries, as well as to investigators conducting child offense and missing children investigations.

Judging by the enthusiastic response of the TXDPS members and Texas Rangers who received this training, IPC has a proven track record of its success. From the absence of child recoveries in 2008 to the start of IPC training in 2009, the statistics compiled by TXDPS since 2010 prove the program’s success.

- Forty seven criminal investigations involving possession of child pornography, sexual assault of a child, human trafficking, enticing a child, and abduction

- Recoveries of over 139 missing or sexually exploited children

- More than 100 observations of suspected high-risk threats to children

Expertise

The third and final tier of the IPC integrative approach, gaining expertise, is ongoing. As demonstrated by the above statistics, TXDPS is developing a cadre of highly trained and knowledgeable troopers skilled in making observations of suspicious behaviors and conducting stops resulting in offender arrests and rescues of numerous children. What the statistics do not show are the even larger numbers of at-risk children and their families whom troopers have identified and provided assistance to without making arrests or removing the children from their homes.

TXDPS members and Texas Rangers are doing outstanding work and acquiring considerable IPC expertise. Acquiring such skills, particularly in the realm of child victimization, entails a never-ending process and requires ongoing effort and continuing adaptability and refinement. Criminal offenders constantly adapt to law enforcement’s methods, and many criminals use state-of-the-art technology and social media to circumvent the best efforts of families and agencies to protect children.

With that caveat acknowledged, some IPC milestones have been established. Troopers conducting IPC interdictions are augmented with multifaceted resources within TXDPS, as well as outside resources from the FBI; other federal and state law enforcement agencies; and victim advocacy, mental health, and social service organizations, among others.

In response to TXDPS’ request for advanced training for TXDPS supervisors, agent investigators, and Texas Rangers, the authors developed an intensive 3-day advanced course for supervisory and investigative personnel. The theme of the course, “What Happens Next?” conveys how the advanced curriculum equips supervisors and investigators with enhanced training in response to calls from IPC-trained troopers needing assistance with suspicious events, recoveries, and arrests.

In July 2012 the authors traveled to Austin, Texas, and conducted the first advanced course. The training was well-received, with many attendees united in their desire for additional IPC training. The members of BAU-3 stand ready to assist TXDPS and other law enforcement agencies with criminal investigations and inquiries regarding child endangerments, victim and offender behaviors, research, and training.

THE IMPACT

The IPC program has gained acceptance and recognition around Texas and beyond. TXDPS has promoted the IPC concept across the nation. It has provided IPC training to approximately 3,592 law enforcement officers from jurisdictions outside Texas. Numerous organizations have requested presentations, consultations, and training from TXDPS, including victim services and child advocacy groups, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the Annual Multi-Jurisdictional Law Enforcement Conference, and the states of New York and New Jersey in preparation for the 2014 Super Bowl. The IPC concept now is established in several state, county, and municipal law enforcement agencies in Minnesota, Georgia, and Ohio. Internationally, the Canadian Royal Mounted Police and the United Kingdom Child Exploitation of Online Pornography organization have expressed interest in creating similar programs.

CONCLUSION

The Texas Department of Public Safety’s Interdiction for the Protection of Children program continues to improve and grow in influence. The beauty of IPC lies in the simplicity of its foundation concept: patrol officers form the backbone of every police agency. Given sufficient training, resources, and managerial support, they will get the job done.

IPC is successful because of the dedicated work of the men and women on the front lines and those who support them. Once law enforcement officers understand the IPC concept and learn the methodology of child victimization, they do whatever is necessary to save children. “The success of the IPC concept, like most law enforcement accomplishments, is attributed to law enforcement’s ‘Three Rs’—Resolve, Resources, and the Right People...who work together to make things better.”4

IPC is an example of what can be accomplished when diverse agencies and dedicated people work together for the common benefit. IPC is making a difference in the lives of children everywhere.

The authors recognize the important contributions in the development and implementation of the program by the following Texas Department of Public Safety personnel: Director Steven McCraw, Lieutenant Derek Prestridge, Texas Ranger Cody Mitchell, Program Supervisor Lexi Quinney, Victim Services Director Melissa Atwood, and Program Manager Heidi Fischer.

For further information about training and services, contact Lieutenant Derek Prestridge, Texas Department of Public Safety, Texas Ranger Division, at 512-424-5783 or Derek.Prestridge@txdps.state.tx.us. To inquire about BAU research, training, and operational services, contact Supervisory Special Agent Michael Yoder at michael.yoder@ic.fbi.gov, Major Case Specialist Wayne Koka at wayne.koka@ic.fbi.gov, or BAU-3 at 703-632-4347.

Endnotes

1 Texas Department of Public Safety, Missing Persons Clearinghouse, http://www.txdps.state.tx.us/mpch/.

2 Major Case Specialist Wayne Koka.

3 Ranger Cody Mitchell.

4 Koka.