Focus on Training

An Evaluation Tool for Crisis Negotiators

By Vincent A. Dalfonzo and Michele L. Deitrick, M.Ed.

A crisis can overtake individuals’ normal capacity to cope, increasing their anxiety and inhibiting their ability to act rationally.1 Crisis negotiators respond to such persons and defuse these situations as peaceably as possible. For dealing with people in these instances, the FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit (CNU) endorses as a core technique the use of active listening skills (ALS). Negotiators using ALS make a conscious effort not only to hear the words persons in crisis are saying but to understand the complete message.2 By doing so, negotiators demonstrate empathy and show that they do not pose a threat to subjects, thus, controlling the tone of negotiations. This helps them build rapport with persons in crisis.3

To maintain ALS, negotiators must practice them. CNU understands this and encourages its teams to participate in the unit’s ALS training. These back-to-back exercises refresh, reinforce, and enhance negotiators’ skills.

For its back-to-back exercises, CNU devised a method to effectively measure the progress and performance of trainees seeking to hone their skills in ALS. Web-based training on this evaluation tool, identical to the course offered to FBI negotiators, is available to law enforcement professionals in international, federal, state, and local agencies.

Exercises

The back-to-back exercises involve two negotiators and an evaluator. Each session features a scenario in which one negotiator acts as a role player in crisis, while the other negotiator represents an active listener and only answers the role player with ALS responses. The evaluator listens to the dialogue and provides feedback to the active listener upon completion of the exercise.

CNU found that the evaluators provided both positive and negative input to the active listeners. However, with no standard evaluation tool, they could not offer consistent, specific feedback on active listeners’ performance. CNU remedied discrepancies in the standardization of feedback.

ALS Target

Similar to practicing ALS, law enforcement professionals participate in annual firearms qualifications. Shooters draw the gun, aim, pull the trigger, and fire, while crisis negotiators using ALS listen, think, and speak. Instead of firing a bullet downrange and hitting a target, negotiators fire a series of responses to an individual in crisis. The “bullets” consist of the eight active listening responses. Just as a bullet makes a permanent mark, crisis negotiator responses leave a lasting impression.

Eight Active Listening Responses

I message: An attempt to confront the subject, encourage positive behavior, and discourage negative behavior (e.g., “I feel (emotion) when you (behavior) because (reason).”)

Paraphrase: Rewording or rephrasing of the subject’s statement in the negotiator’s words

Emotion label: Identification and articulation of underlying feelings

Summary: Periodic review of the main parts of the subject’s story and the accompanying feelings

Effective pause: Silence before or after saying something meaningful

Minimal encourager: Brief responses (sounds) that indicate the negotiator is listening

Reflection: Repeat of the last few words spoken by the subject

Open-ended question: Questions requiring more than a “yes” or “no” answer, typically beginning with “who,” “what,” “when,” “where,” and “how” (The authors discourage the use of “why” because it potentially is accusatory and confrontational.)

Source: Gary W. Noesner and Mike Webster, “Crisis Intervention: Using Active Listening Skills in Negotiations,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, August 1997, 13-18, available at http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/fbi/crisis_interven2.htm.

Firearms instructors easily can check a target and provide the student with a quantitative score. “You fired 50 rounds, and 45 hit the target. Your result is 90 percent.” They also may provide feedback to the shooter regarding the causes of missed shots. “You fired high and to the left. Let’s adjust your grip and focus on your sight picture.” Such qualitative input enables the student to adjust and correct for the inaccuracies.

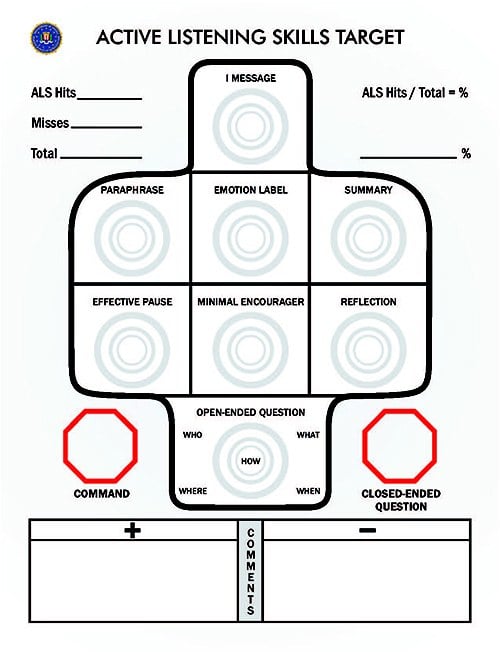

Rating a back-to-back exercise resembles scoring a target at a firearms range. Therefore, evaluators can use similar quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods. They can record the responses and determine if the negotiator consistently employed ALS. To help with this process, CNU developed the ALS target (figure 1).

During back-to-back exercises, evaluators document active listener responses on the target, which creates a visual representation of the student’s performance and helps paint a picture of the ALS applied. The target also can highlight incorrectly applied responses. This process directly correlates with research in the area of deliberate practice and expert performance.4 Immediate feedback gives students the chance to reflect on their performance and make necessary adjustments to improve specific skills.5

The target was designed to enhance the learning experience and provide an accurate reflection of negotiators’ performance by providing both qualitative and quantitative feedback. Documentation of active listeners’ responses during back-to-back exercises using the ALS target allows evaluators to comment on qualitative aspects (e.g., tone, delivery, and timing). It also allows for a quantitative backdrop to provide support for scoring. For instance, if active listeners remain consistent a majority of the time but only use three of the eight skills, evaluators may point this out and encourage them to broaden their skill sets.

The ALS target serves as a valuable assessment tool for evaluators. It provides them with a visual representation of any patterns, inconsistencies, or performance gaps in active listeners’ responses. Then, evaluators may take the identified issues and quickly correct any inaccuracies. Additionally, the tool benefits active listeners because it may help reveal their understanding or misunderstanding of ALS and allow for consistent feedback across back-to-back exercises.

Scoring

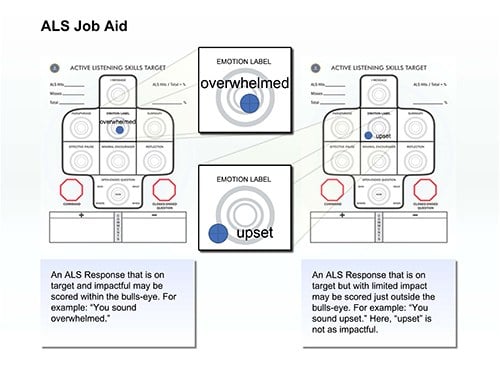

The ALS target contains several areas the evaluator uses to record feedback. Correct ALS responses, or “hits,” are noted on the silhouette. Non-ALS responses, or “misses,” are marked outside the boundary of the silhouette. The stop sign outlines record common misses, and the comments boxes allow for more descriptive or qualitative feedback (figure 2 provides helpful hints for scoring).

After completion of back-to-back exercises, the evaluator tallies the hits and misses and records the results on the appropriate lines. Then, the evaluator divides the “ALS hits” line by the total of both, revealing the percentage and providing a quantitative score—numerical data feedback for the student. The positive and negative comments boxes allow for qualitative feedback to the student.

Web-Based Training

After developing and field-testing the target, CNU worked with the FBI’s Training Division (TD) to determine how to deliver appropriate training effectively and efficiently, initially to over 350 of the agency’s crisis negotiators assigned to 56 field offices throughout the United States. Deeming traditional classroom training expensive and impractical, CNU and TD designed an internal online course that reviewed the basic principles of ALS, outlined qualitative and quantitative feedback, and required students to provide real-time responses to a video of a recorded training scenario.

CNU later made the training available to external entities. Today, crisis negotiators in state, local, international, and federal law enforcement agencies can benefit from the course, titled “Active Listening Skills Target: An Evaluation Tool for Crisis Negotiators” and offered completely online. The course takes approximately 1 hour to complete.

Course Access

The FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit offers the course “The Active Listening Skills Target: An Evaluation Tool for Crisis Negotiators” to law enforcement professionals who are members of the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal (LEEP), located at https://www.cjis.gov/CJISEAI/ EAIController. LEEP members must request access to the Law Enforcement Negotiation Support (LENS) special interest group. The course, approximately one hour in length, is available on the LENS homepage.

Conclusion

Negotiators face many tense situations involving persons in crisis. Active listening skills are important in these situations, and negotiators must learn how to employ them effectively. To this end, the ALS target is a tool for evaluators to provide timely, effective, and accurate feedback to students, who then can reflect upon and improve their performance. The training designed by the FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit and Training Division teaches evaluators and students how to benefit from this tool and, thus, enhance their skills.

Helpful Hints for Evaluators

- Copies of the ALS target on legal paper provide ample room to write.

- Evaluators must include descriptive words, along with the “bullets,” on the target (e.g., emotion label: overwhelmed, distraught, loved).

- Students should receive ALS targets at the end of a feedback session for them to self-assess. Pen, rather than pencil, serves best to mark the target for use as a visual aid for them to recognize where to adjust their “aim.”

- Students should print ALS targets and practice by viewing interviews on television and other back-to-back sessions.

- One technique for useful feedback is highlighting keywords from the active listener’s response.

Ms. Deitrick is an instructional systems specialist in the FBI’s Security Division in Washington, D.C. She can be contacted at Michele.deitrick@ic.fbi.gov.

Supervisory Special Agent Dalfonzo serves in the FBI’s Critical Incident Response Group, Crisis Negotiation Unit, in Quantico, Virginia. He can be contacted at Vincent.dalfonzo@ic.fbi.gov.

Endnotes

1 Gary W. Noesner and Mike Webster, “Crisis Intervention: Using Active Listening Skills in Negotiations,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, August 1997, 13-18, accessed June 5, 2015, http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/fbi/crisis_interven2.htm.

2 For information on active listening skills, see Noesner and Webster, “Crisis Intervention.”

3 Ibid.

4 K. Anders Ericsson, “Deliberate Practice and Acquisition of Expert Performance: A General Overview,” Academy for Academic Emergency Medicine 15, no. 11 (November 2008): 988-994, accessed June 5, 2015, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00227.x/pdf.

5 Ibid.