From the Archives

Historic Guardians of Our Nation’s Capital (April 1976)

By George R. Wilson

[Published in its original form]

Founded 115 years ago, the MPD’s [Metropolitan Police Department] past has been closely intertwined with many remarkable events that have had a profound impact on the course of our Nation’s history.

Activities commemorating significant events and developments in our country’s history will occur across this land during the Bicentennial Year. As our Nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., will be a focal point for these Bicentennial activities, and millions of touring Americans, as well as foreign visitors and dignitaries, are expected to visit this beautiful city in 1976.

The Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) has the unique distinction of being the Capital City’s major law enforcement agency. It will shoulder the burden of law enforcement responsibilities attendant to these celebrations in Washington; however, assignments of this magnitude and significance are not new to the MPD. Founded 115 years ago, the MPD’s past has been closely intertwined with many remarkable events which have had a profound impact on the course of our Nation’s history.

Early Police Efforts

Acts of Congress in 1790 and 1791 authorized the establishment of an area, to be called the District of Columbia, which was to be our new National Capital. It was comprised of portions of land ceded to the Federal Government by the States of Virginia and Maryland. Initially, constables appointed by these two States performed some law enforcement duties in District areas located on their respective sides of the Potomac River. Congress convened in the District for the first time in 1800.

In 1802, when the original charter of Washington was approved, police authority was centralized, and power was granted to establish patrols, impose fines, and initiate inspection and licensing procedures. Although there was ample authority for constituting the night watches and patrols, this force remained quite small for many years. In fact, it was not until 40 years later that a regular night watch was established, when Congress provided for an auxiliary watch for the protection of public and private property in the city of Washington.

This auxiliary watch consisted of a captain and 15 policemen. They only served at night and were paid from funds of the U.S. Treasury. The headquarters of the watch was established in a guardhouse located in the main business area. Persons arrested were locked up overnight and then taken before the magistrate before 9 o’clock the next morning.

Mr. Wilson has been a member of the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) for over 23 years as a patrolman, detective sergeant, and firearms examiner. He has a deep personal interest in police history, particularly pertaining to the MPD, and has done considerable research in this regard.

Rules adopted for the watch provided that in case of fire, riot, or disorderly assemblage, a report was to be made to the captain of the watch. The rules were also very definite as to a watch member’s sobriety, and a single instance of intoxication was justification for the immediate removal of the offender.

Civil War Years

It is difficult for us to fully realize the extent of the tumultuous conditions that existed in the Nation’s Capital in mid-1861. The country was in the first months of a terrible fraternal war. At the conflict’s outbreak, the military advantage was with the South. In view of this, the Capital City was in constant danger of being attacked and overrun by soldiers of the Confederacy. To thwart such a potential, forts were eventually erected and manned in a ring around the entire District. With the vast military buildup, thousands of troops poured into the District and numerous camps were established in the nearby Virginia and Maryland countrysides. For over 5 miles along the Maryland side of the Potomac River alone, there were continuous Army encampments. One observer commented that not far from the Army encampments there was a tent and shack city which, for the most part, represented “the longest and busiest brothel in the world.” Hordes of unsavory characters descended upon the Federal city–crooks, gamblers, prostitutes, pickpockets, and thugs.

In Washington, every available building had been converted into a barracks, warehouse, or hospital. The number of Government employees increased tenfold with more coming into the city daily. Each sought to find a room to live in and food to sustain life.

The movement of the staggering volume of supplies needed to support the civilians and the Army in and about Washington kept all roads leading to the city clogged day and night. Livestock were driven into the city where they grazed at various sites until slaughtering time. The best grazing areas were the fields just south of the White House and around the half-finished Washington Monument.

Metropolitan Police Department Established

Structure used as police headquarters until mid-1893.

Observing this vast influx, build-up, and confusion, President Abraham Lincoln recognized that the night watch was inadequate for coping with it and that the District of Columbia was in desperate need of a regular police force. Upon his recommendation, Congress approved an act on August 6, 1861, creating the Metropolitan Police Department. However, even after Congress established this department, President Lincoln refused to let the matter drop at that. On August 13, 1861, he personally requested Zenas C. Robbins, Esq., a member of the newly created Board of Metropolitan Police Commissioners, to take the first railroad train to New York and, upon arrival, to thoroughly familiarize himself with the features of the New York Police System and the experiences of its leadership. The New York Police System had been modeled after the famous Metropolitan Police of London. This latter force was then recognized as the world’s most outstanding police organization. It was upon the results of Mr. Robbins’ study of the New York Police System that the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia was modeled.

In September 1861, William B. Webb was appointed the first superintendent of police of the District of Columbia. At that time, the authorized strength of this force consisted of a superintendent, 10 sergeants, and a sufficient number of patrolmen as might be necessary, but not to exceed 150. Up to 10 precincts were authorized.

Applicant Selection

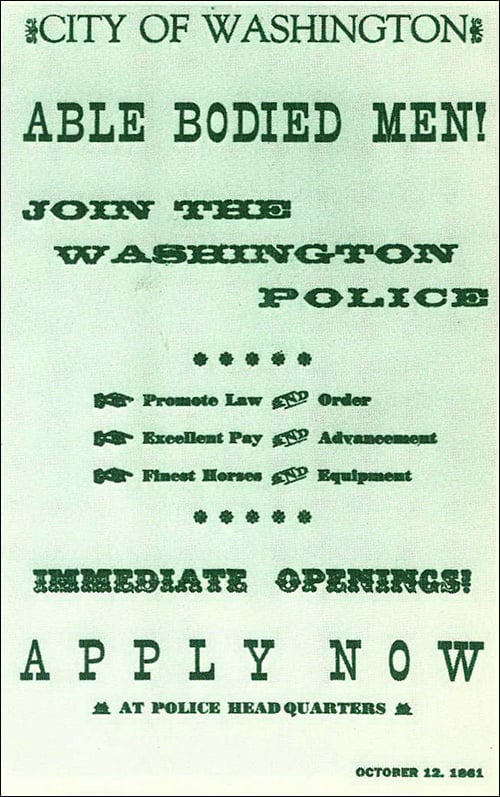

Upon assuming office, the new superintendent began the task of investigating and qualifying applicants for the authorized complement. Although speed was essential, finding good men was equally important. This was no easy task, however, as two opposing armies were also seeking to press into service all able-bodied men available.

A police applicant had to meet several prerequisites. He had to be a U.S. citizen, able to read and write the English language, a resident of the District of Columbia for 2 years, and never have been convicted of a crime. Each also had to stand at least 5 feet 6 inches tall, be between 25 and 45 years of age, in good health, of sound mind, and possessing good character and an upright reputation. Superintendent Webb made it his policy to interview each candidate personally, working an average of 20 hours a day during this process. Local doctors volunteered to give the required physical examinations to applicants, but from all reports, these seem to have been rather perfunctory in nature.

The superintendent of police’s salary was $1,500 annually, with sergeants earning $600 and patrolmen $480 a year.

MPD recruitment poster from 1861.

By the morning of September 11, 1861, the sergeants and most of the personnel for staffing two precincts had qualified for duty and were sworn in. The swearing-in ceremony was performed in the Senate wing of the Capitol Building. The men immediately went to work–or at least half of them did, because the force was divided into two 12-hour tours of duty. These tours were from midnight to noon and noon to midnight. The men on the force worked 7 days a week with no days off and no provisions for any vacation. They were issued no equipment. Badges were unobtainable and members were supposed to supply their own handguns. (When badges were later distributed, the U.S. Capitol was used as the shield’s background–a situation that still exists today.) Officers were prohibited from carrying shotguns and rifles and were not allowed to carry canes or umbrellas.

Lincoln Assassination

A great tragedy struck the city and the Nation on the night of April 14, 1865. That evening, President and Mrs. Abraham Lincoln decided to visit Ford’s Theatre, located just a few blocks from the White House, to witness the performance of a play entitled “Our American Cousin.” During the second act, President Lincoln, occupying a private box with his wife and another couple, was shot in the head from the rear by an assassin. The assassin, John Wilkes Booth, hastily and dramatically fled the playhouse.

The Metropolitan Police Department assisted in the War Department’s intense investigation to locate the assassin Booth and other conspirators. Although Booth was tracked down by U.S. soldiers in a barn near Port Royal, Va., several of the other conspirators charged were arrested in Washington, Maryland, and Virginia based on information developed through police and military investigation.

The following account of this tragic event was recorded longhand in the 8th Precinct arrest book, shortly after it occurred:

“Between the hours of ten and eleven o’clock at night, a telegram was received at the 8th Precinct station from headquarters that Abraham Lincoln, President of the U.S., had been shot while sitting in a private box at Ford’s New Theatre at Tenth Street, West, between E and F Street, North. Also, that the Honorable William H. Seward, Secretary of State, had been stabbed and seriously injured in the neck and his sons–F.W. Seward, Assistant Secretary of State and Major C. Seward, U.S.A.–had been fatally injured.1 The assassin or assassins were at time unknown. At a later hour, it became currently reported J.W. Booth was the person who shot the President.

“The excitement was great throughout the precinct and feeling deep but the people were orderly and quiet. The whole force were immediately put on duty by order of Superintendent Richards and were vigilant in the discharge of their duty. The sad intelligence was received by them with feelings of deep regret and an unbound feeling was manifested to avenge the death of their beloved Chief Magistrate. The gloom that overshadowed the Nation by the sad occurrence deeply affected the whole force and brought forth many heartfelt sympathies for the Nation’s loss.”

Apprehension of Assassin of President Garfield

In 1881, the Metropolitan Police Department was once again involved in a tragic event of major national significance. The morning of July 2, 1881, was clear and warm and there was nothing to indicate that a great crime was about to be committed. A carriage bearing President James A. Garfield and Secretary of State James G. Blaine stopped at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Depot on B Street in the District. The President and the Secretary walked slowly up the steps leading to the waiting room and were about to enter the large reception area of the main depot when two shots were suddenly fired in rapid succession. The target, President Garfield, fell, mortally wounded. The assassin swiftly made his way out to his waiting carriage; however, he was immediately seized by Pvt. Patrick Kearney of the Metropolitan Police Force.

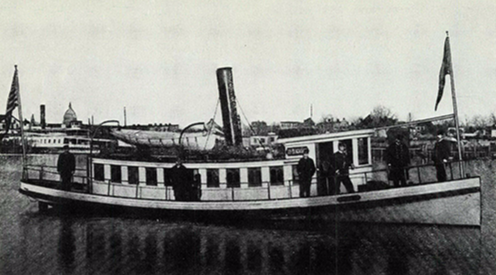

The “Joe Blackburn,” an 87-foot police patrol boat purchased in 1886 for Potomac River harbor policing in the District of Columbia.

After suffering for several weeks, President Garfield died on September 19, 1881, in New Jersey. The assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, admitted shooting the President, was subsequently convicted and, thereafter, executed for this crime at the District of Columbia jail on June 30, 1882.

Other Developments

The dawn of the twentieth century saw the Metropolitan Police Department making steady progress, particularly in the field of improving working conditions for all personnel. Shorter working hours, increased pay, and the furnishing of uniforms by the department rather than by members increased morale and efficiency.

In 1881, the first women were appointed to serve as matrons and, in 1918, three policewomen were recruited to form the nucleus of the Women’s Bureau.

In the old days a rookie became street-wise by walking a beat with an older, more knowledgeable patrolman. However, time and experience dictated the necessity of a formal training period for recruits. Consequently, in 1930, the department’s first police training school was established, offering a 3-month course of instruction. Initially, instruction was given almost entirely by members of the department, but the program was later expanded to include various outside experts from many fields.

The policeman of 1861 would be amazed at the modern-day Metropolitan Police Department. He would marvel at the mere existence of police helicopters, motorcycle units, police dogs, high-speed boats, and the use of computers and sophisticated communications equipment in fighting crime. Moreover, the growth of our Nation’s Capital and the Metropolitan Police Department itself would be astonishing to the less than 200 member force of 1861.

Today the police command totals 4,550 members. Of these, 336 are females who perform the same duties as their male counterparts. Just seeing a female performing patrol duties would certainly have raised the eyebrows of an 1861 police officer.

The contemporary Metropolitan Police Department has an annual budget of almost $91 million. Organizationally, the department is divided into four bureaus: (1) field operations, (2) administrative services, (3) technical services, and (4) inspectional services. The Field Operations Bureau includes patrol, criminal investigations, traffic, youth, and special operations divisions. Among Patrol Division elements are the Harbor Police. This unit patrols the Potomac River harbor areas of Washington, utilizing three cabin cruisers, four Boston Whalers, and three rowboats.

Current headquarters for the Metropolitan Police Department, Washington, D.C.

The MPD officer’s role today may include participation in a variety of assignments. These could range from overseeing mass demonstrations, to escorting visiting dignitaries, to patroling or handling crowds along the presidential inauguration route or to directing tourists to national monuments or cherry blossom festivities along the Tidal Basin.

Our overview of some highlights in the history of the Metropolitan Police Department brings us once again to 1976, a time when the department faces the challenge of helping millions of visitors, as well as Washington residents themselves, enjoy our Nation’s Bicentennial Celebration in the Capital City. We are confident that when the history of 1976 is recorded, it will reflect that, as in our past, we met this challenge also–successfully and admirably.

From the Archives is a new department that features articles previously published throughout the 80-year history of the Bulletin. Topics include crime problems, police strategies, community issues, and personnel, among others. A link to an electronic version of the full issue will appear at the end of each article.

Endnotes

1 Initial news accounts reported that Clarence Seward and Frederick Seward, the nephew and son, respectively, of Secretary of State William H. Seward, were seriously injured by one of the conspirators on the same evening as the Lincoln assassination. Clarence Seward was an orphan raised as an adopted son by Secretary Seward. Actually, these first reports were inaccurate as it was later learned that the persons injured at the Seward residence included the Secretary himself and his sons, Frederick, who received serious wounds, and Augustus, whose wounds were superficial. All three Sewards recovered from injuries inflicted during this incident. The account reflected in the arrest book must have been based on early erroneous reports in this regard.