From the Archives

Railroad Crime: Old West Train Robbers to Modern-Day Cargo Thieves (February 1977)

By Thomas W. Gough

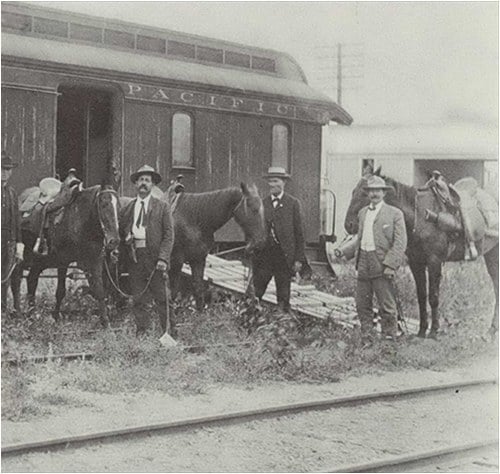

Members of the Union Pacific “Rangers.”

[Published in its original form]

Many new law enforcement officers are genuinely surprised to learn that America’s railroads employ full time law enforcement personnel to protect their interests. Use of personnel in such a role goes back many years to 1855 when Allen Pinkerton had the distinction of becoming the first railroad law enforcement officer hired to protect railroad interests. As the rails were laid westward in the 1860’s, railroad law enforcement experienced rapid growth and became a vital link between the railroads and other law enforcement agencies.

Pinkerton encouraged the use of burglarproof safes in all railroad express cars. By using such a heavy safe, any outlaws intending to rob the train had to use a large charge of black powder or dynamite to blow it open. The resulting blast’s magnitude usually destroyed the contents of the safe, as well as the roof and sides of the express car. Pinkerton also recommended the employment of express guards heavily armed with high-powered rifles.

The infamous “Hole-in-the-Wall Gang” first struck a defenseless railroad in August 1878, when they held up and robbed a Union Pacific train at a site near Carbon, Wyo. Several days later, the gang reportedly killed two posse members—a deputy sheriff from Rawlins, Wyo., and a Union Pacific detective—who had been in pursuit disguised as prospectors.

“The Wild Bunch”

Probably the most colorful and best known “Wild West” railroad crime occurred on June 2, 1899, near Wilcox, Wyo. The Wild Bunch, consisting of the roughest elements of the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang (primarily Harvey Logan, alias “Kid Curry,” Robert Leroy Parker, alias “Butch Cassidy,” and Harry Longbaugh, alias “The Sundance Kid”), forced the Union Pacific Overland Limited crew to uncouple the express car and remove it some distance from the passenger cars. Once this was done, the safe in this car was dynamited, and in the process, the entire express car was destroyed. Thereafter, a select group of railroad special agents formed a posse called the “Rangers” and chased after The Wild Bunch.

Thomas W. Gough Staff Assistant to the General Director, Security and Special Service Department, Union Pacific Railroad Co. Omaha, Nebraska.

This special outlaw-hunting posse (perhaps one of the first “SWAT” teams) had a specially equipped baggage car designed to carry eight members and their horses. The group was led by a former Lincoln County, Wyo., sheriff who later became the chief special agent for the Illinois Central Railroad. Upon notification that a train robbery had occurred, the Rangers were promptly taken to the scene by train in their special car. Upon arrival, they relentlessly pursued the outlaws on horseback.

Express car blown up by “The Wild Bunch” at Wilcox, Wyo., June 2, 1899.

Outlaw members of the gang all reportedly met violent deaths in diverse locations in Kansas, Missouri, Texas, Utah, Colorado, and South America. Harvey Logan, the gang leader, was arrested at Knoxville, Tenn., in 1902 on a Federal charge stemming from another crime. He escaped in 1903 and pulled his last job on June 7, 1904. He, along with two other masked men, reportedly held up a Denver & Rio Grande train near Parachute, Colo. Their only loot consisted of a worn gold watch taken from an express guard. The next day, members of a posse wounded Logan, and he reportedly thereafter took his own life.

Other Bandits

There were other gangs, too. Sam Bass and the “Collins Gang” made a big strike against the Union Pacific on September 18, 1877, at Big Springs, Nebr. On this occasion, they robbed the express car, obtaining $60,000 in 20-dollar gold pieces.

Less well known, but every bit as troublesome, were the lone bandits such as “Parlor Car Bill Carlisle,” who hit the Union Pacific four times. Carlisle once wrote a Denver newspaper and identified himself as the culprit after two hoboes were falsely accused of perpetrating one of his crimes. He also announced to the newspaper his plans for his next holdup, specifying the train he intended to rob. As a result, special guards were assigned to this train, but Bill disarmed one of them near Hanna, Wyo. and then forced him to collect the loot.

“Shoot Fast and Ride Hard”

From the beginning, the railroad special agents’ responsibilities have been similar to those of public law enforcement—the protection of society (both life and property) and the prevention and detection of crime. The railroad special agent was a colorful part of the old Wild West. Being able to shoot fast and ride hard were important skills in the late 1800’s. In addition to train robbers, there were also station holdup crooks, pickpockets, con men, and bootleggers to contend with. Because of his mission in countering such problems, the railroad special agent of the old West was considered as nearly a duly commissioned law enforcement officer as is his modern-day counterpart.

Modern Railroad Police

The railroad special agent of today is educated and well trained and equipped. Many railroads utilize the Association of American Railroads (AAR) National Railroad Police Academy at Jackson, Miss., to provide formal law enforcement training for new personnel. The director of training of the AAR’s Police and Security Section coordinates entry level and advanced law enforcement training related to railroad needs. Approximately 500 railroad police attend training at this academy each year. It is located at the Mississippi State Law Enforcement Officers’ Training Academy, one of the finest institutions and facilities of its type in the country.

Railroad police student attend two 2-week sessions covering areas germane to railroad law enforcement. Basic law enforcement subjects covered include: Criminal law, mechanics of arrest, crime scene search, coordination with other law enforcement agencies, and firearms proficiency. Academy instructors include enforcement and security experts from the various railroads, as well as representatives of the Mississippi State Highway Patrol and special agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

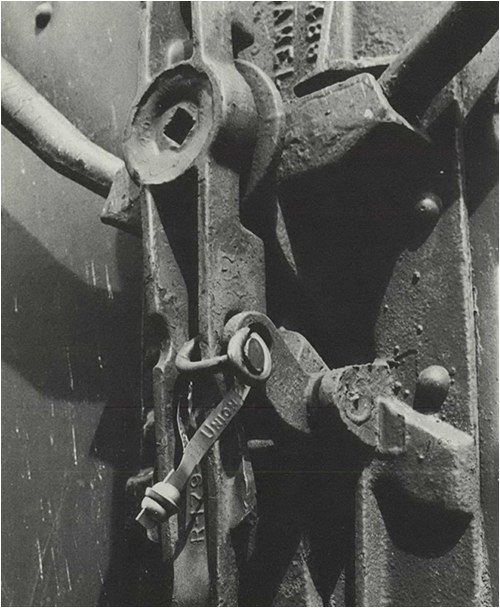

Boxcars are usually sealed with a small metal seal which provides proof-of-load security only. Some form of additional security is usually applied, and in this case, a 60-penny nail is applied to the door hasp to prevent easy entry.

While attending the academy, railroad special agents participate in a particularly excellent firearms training program. Many railroads require their special agents to fire a minimum score of 60 out of a possible 100 on the Practical Pistol Course during the training. This stimulates many special agents to become interested in competitive combat shooting, and several railroads are usually represented at police pistol competition championship matches held each year at Jackson, Miss.

Another training medium is the International Railroad Police Academy Course. This consists of a 2-week session designed for management-level personnel held annually in Chicago for the past 26 years. Training time is divided between a comprehensive review of the state-of-the-art of railroad law enforcement and management training.

Various States specifically recognize individual railroad’s efforts in training. In California, the Commission of Police Officer Standards and Training (POST) issues a basic POST certificate to railroad special agents successfully completing the Southern Pacific Railroad’s 240-hour academy. This certificate indicates that the holder has completed the necessary basic training required for a law enforcement officer in that State.

Responsibilities

The railroad special agent’s responsibilities include the protection of personnel, cargo, and property. Investigations relating to thefts of cargo, burglaries of company property, and acts of vandalism occupy most of the agent’s time. However, train derailments, extortion attempts, crimes of violence, and many other felony and misdemeanor crimes that involve railroad interests are also investigated by railroad special agents.

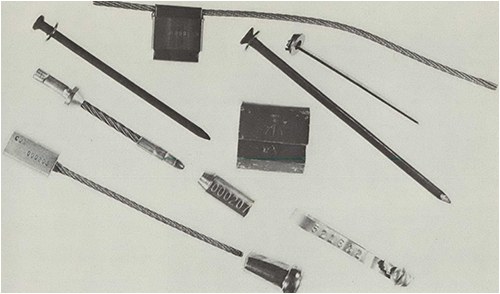

Theft losses from rail shipments in 1974 amounted to $15.2 million and in 1975 rose to $20.7 million. It may be surprising, but often cargo worth thousands of dollars is loaded on one coast and transported across the country protected only by a small and fragile metal seal. The seal’s purpose is to show proof-of-load security only. To cover such weaknesses in security, railroad police, marketing, and traffic sales departments all work with the various shippers to develop security awareness. Cargo crime is often reduced after the railroad police have helped the shipper analyze his transportation security needs and the shipper has thereafter taken necessary protective actions. This analysis includes security considerations relating to methods of packaging the product, shipping schedules, routes of shipment, and the desirability of applying a security device designed to prevent casual theft.

Frequently, if a thief is smart enough to close the railroad boxcar door following a theft, the loss is not discovered until the boxcar reaches its destination. Claims for theft or loss are paid by the railroads based on the records maintained regarding the car seals—from the last good record to the first bad record. “No record” is considered a bad record. Therefore, it benefits each railroad handling a load to maintain proper inspection records concerning such cargo throughout its transit.

Just a few of the various devices used by the railroads and shippers to seal loads, and in some instances, to assist in preventing easy entry.

Cargo Security

Security of cargo is a high-priority interest of the railroads; however, the problem must be approached from a cost-effective basis. It is often financially unrealistic to apply $10 worth of security devices to a boxcar every time it is loaded.

By utilizing the computer, and through faster methods of handling claims, the railroads are identifying loads with high-theft risks. They can then be afforded special security. Physical inspection of loads at intervals en route helps the railroads identify theft prone routes and areas where special attention must be given to prevent theft. Sometimes altering train schedules or making route changes solve particular theft problems.

Railroad police provide vehicle and foot patrols for their yards and industrial areas where freight cars are located. These patrols place special emphasis on discouraging trespassing on railroad property. In some instances, railroads are using dog and handler patrols to deter crime in railroad yards. When high-value or risk loads have to remain for a period in areas with a crime potential, a stakeout is often provided to insure their protection. Onsite teams may stakeout a particular cargo load or a group of loads. Remote surveillance can be accomplished through the use of radio transmitters with noise-activated microphones. Closed-circuit television and high-powered infrared optical devices also are employed in certain instances.

Obviously, railroad special agents cannot provide continuous protection for approximately 2 million freight cars scattered over more than 200,000 miles of mainline track. The Eastern United States provides the greatest security challenge to the railroads as rail yards are often located in densely populated areas where socioeconomic conditions are a factor in breeding crime.

Hiring security personnel is only one aspect of a program for protecting cargo on railroad property. The use of adequate fencing and extensive lighting, as well as a program of good housekeeping and other measures, can also be complementary theft deterrents. It is recognized that fences are a costly budget item and they frequently stop only the casual thief. Fencing of rail yards has proven ineffective in some areas as the fences have been vandalized or destroyed faster than maintenance crews can repair them. However, keeping company property in good repair with an uncluttered and orderly appearance, as well as the availability of lots of artificial light during darkness hours, have been effective security aids in some areas. The brightness and neat appearance avoids creating an image which could be capitalized on by would-be thieves.

Stealing railcar journal brass has been a source of income for some thieves for many years. The railroad car axle pictured has a brass journal on each end. Pictured are several different pieces of journal brass, and each may weigh from 10 to 30 pounds.

Outsiders Usually Involved

Other modes of cargo transportation find that many of their losses are due to thefts perpetrated by employees. Railroad thefts, however, usually involve outsiders. This phenomenon may be attributed to the industry’s early development of an internal security element and firm support of prosecution of any persons determined to be involved in criminal acts.

Once a theft from a load is ascertained, agents are assigned to establish where the theft occurred. Unless there is evidence that the load was entered where the theft was discovered, there is usually little chance of apprehending and prosecuting the parties responsible as just locating where the crime occurred can be quite difficult. Occasionally when stolen cargo is recovered, investigators find they are unable to prove that the cargo had been stolen from a particular car because some shippers do not record the serial numbers of the products they ship. This problem can be solved only if the shipper is convinced that accurate documentation is a necessity. Whenever available, serial numbers of stolen cargo are entered into the National Crime Information Center.

Precious Metal Thefts

Railroads are often victims of precious metal thefts which involve losses of copper communications wire and railcar journal brass. Often, the same thieves that steal copper wire from telephone and electric companies also steal it from the railroads, who utilize extensive telephone networks and rely on thousands of miles of communication lines to relay train signals.

Stealing journal brass requires more effort on the thief’s part than snipping copper wire. Brass thieves remove journal brass bearings from the car wheel axle by lifting the car to remove the weight from the axle. After removing the journal brass, it is usually sold for scrap. The initials of the railroad installing the brass are always stenciled on it. Fortunately, this type of car axle is being replaced by new roller bearing equipment, and such actions should eventually eliminate this particular theft problem.

Support From Others

The railroads greatly appreciate the support received from public law enforcement agencies. America’s estimated 4,500 railroad police could not begin to protect such a vast responsibility without a tremendous cooperative effort from all law enforcement agencies.

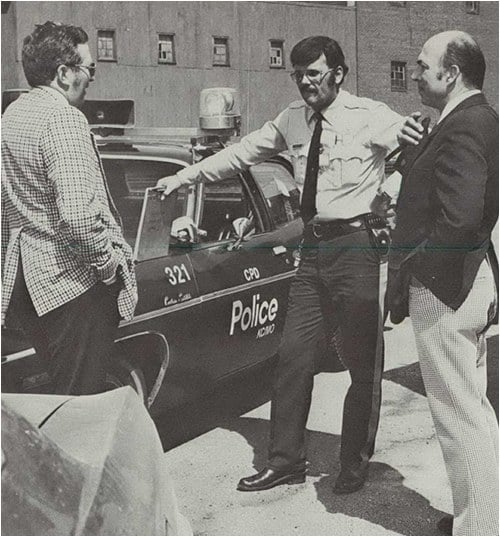

Railroad agents work closely with the FBI on appropriate theft from interstate shipment cases. As most cargo thefts and losses of company property are usually within the purview of local jurisdictions, a close working liaison is maintained with many city and county law enforcement officers, as well as with local prosecutors.

On the national level, the Association of American Railroads, through member railroads, participates in various national efforts striving to reduce cargo crime. In this regard, 12 of the anti-cargo-crime “City Campaigns”1 have active railroad representation on their steering committees.

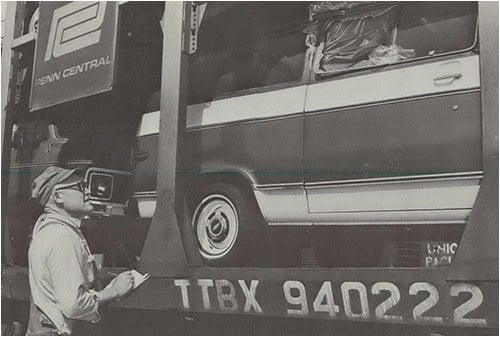

Vandals broke this van window with a rock. Railroad personnel record the damaged load, make temporary repairs, and attempt to stop any acts of vandalism observed.

A representative group of different railroad chief special agents comprise the AAR’s Police and Security Section Committee of Direction. This committee provides guidance for the industry and is responsible for arranging the annual railroad police conference held in conjunction with the International Association of Chiefs of Police National Conference. This railroad conference provides a medium for top railroad security and enforcement people to discuss common problems and to seek sound solutions.

Some railroads approach cargo crime from yet another angle—by participation in activities of the American Society for Industrial Security. Through this organization, professional security personnel employed by shippers and carriers exchange valuable information relating to their common cargo-theft problem.

Railroad police also participate in local, regional, and national seminars and panel discussions called to discuss various aspects of the cargo problem. And, of course, through informal contacts during the transaction of regular business, railroad police exchange information with representatives of various agencies which have a mutual interest in reducing cargo security problems.

Public law enforcement agencies assist the railroads in many areas. These include investigation of railroad crossing accidents, internal crime problems, and vandalism or theft of company property.

Without the valuable aid and assistance of the public sector of law enforcement, railroad security personnel would have a much tougher job, and vice versa. The true value of this relationship is mutually beneficial.

Illegal Trespassing

A traditional area of railroad law enforcement relates to efforts to control the railroad-riding hobo or knight-of-the-road. The prevalence of this colorful figure is almost a thing of the past. Today’s illegal train rider often has a better chance playing Russian roulette as the speed of today’s trains, combined with the frequent unfamiliarity of the rider with the train’s movement, presents a most dangerous situation. Many young people have never ridden a passenger train and yet, surprisingly, some of them will not hesitate to hop a freight train and ride under the dual wheels of a piggy-back trailer mounted on a railroad car. “Riding the rails” is illegal in most States, and due to this factor and the many serious hazards involved, it should be discouraged whenever possible.

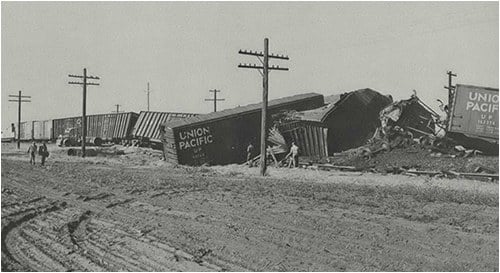

Train derailments are not as prevalent as they once were. Railroad police with the assistance of local law enforcement agencies provide protection against looting.

Another form of trespass stems from the urban congestion prevalent in many regions. Invariably, if people are allowed to travel across, or play on, railroad property, problems will eventually develop. The excitement of placing objects on the tracks or attempting to impede or stop a powerful locomotive and train has often attracted the interest of people of different ages. Many think it’s harmless fun to see trains run over objects placed on the track. This game for many is limited to placing small coins on the track. For others, however, it sometimes progresses to large objects such as rail crossties, oil drums, or even automobiles. Track obstruction sometimes even of a small nature, can cause serious train derailments.

Malicious vandalism of railroad signals and switches costs the railroads millions of dollars each year and in many instances poses potential or actual hazards for the trains. Vandalism to cargo carried by the railroads is also a serious problem. The total claim payout for cargo vandalism exceeds that paid out for actual thefts. Throwing of rocks and other objects at trains is a fairly common problem and this sometimes progresses to shooting at trains, their cargoes, and signals.

Strict enforcement of trespassing laws and maintenance of a record of previous offenders discourage trespassing and attendant vandalism. Presenting informational programs to children attending schools near rail yards and tracks has been a successful means of preventing railroad property from becoming a playground. When the hazards of trespassing and the illegal nature of related activities are illustrated and emphasized, the problem usually is substantially eliminated.

Train Wrecks

Under the Federal Train Wreck Statute (title 18, U.S.C., sec. 2153), the FBI has jurisdiction when a person (or persons) willfully attempts to, or actually does, derail, disable, or wreck a train engaged in interstate or foreign commerce. Violations under the act could also be present under various specified conditions if a person (or persons) willfully damages or attempts to damage railroad property or facilities used in connection with interstate or foreign commerce.

If a train is wrecked, disabled, or derailed, regardless of cause, railroad special agents provide for security and crowd control at the scene during these serious situations. They also, of course, offer their assistance to appropriate public officials who may have jurisdiction for investigating such incidents.

Local law enforcement agencies and railroad police in most areas have a close working relationship. In this scene, two Union Pacific special agents discuss a mutual problem with a Kansas City, Mo., patrolman.

Conclusion

The next time you are waiting for a train to clear a road crossing, remember this article and scan the train with a professional eye. You might see or think of something related to railroad security that hadn’t been noticed before. If so, contact the railroad involved (many cities are served by several railroads) and someone will be able to direct you to the railroad police or special agent or investigator. Most cities with rail yards also have a railroad special agent in residence. Usually the territory between major terminals is assigned to a special agent working out of the major terminal. When there is a railroad track, somewhere not too distant there is usually a railroad special agent assigned. Your input will be appreciated and could contribute to improving the security of an important element of America’s transportation system.

The railroad police appreciate the frequent assistance they readily receive from various law enforcement agencies. They in turn are willing to assist law enforcement agencies, whenever and wherever possible, consistent with their railroad responsibilities. Through cooperation and effective communication, everyone’s job in this area is made easier and more efficient.

From the Archives is a new department that features articles previously published throughout the 80-year history of the Bulletin. Topics include crime problems, police strategies, community issues, and personnel, among others. A link to an electronic version of the full issue will appear at the end of each article.

Endnotes

1 In recent years, at Presidential direction, the U.S. Secretary of Transportation had provided leadership, guidance, and technical assistance in coordinating the efforts of Federal agencies and the transportation industry in the search for solutions to cargo security problems. The railroad police have eagerly accepted this help and have joined with pertinent Federal agencies, State and local officials, and various transportation components in a spirit of cooperation in combating cargo crime through a National Cargo Security Program (NCSP). As a key part of the NCSP, the “City Campaigns” seek to reduce cargo crime through effective interaction and communication between various transportation industry elements and the diverse levels of law enforcement including prosecution components. Cities participating are major ones with significant transportation industry concentrations and attendant security problems.