Police Practice

Providing Cell Phones to Those in Need

By Amanda Chapman, M.S.S.W.

Cell phones and the technology they possess bring a wealth of advantages to community members. They connect people to family and friends, provide access to news and information, link to community resources, and enable help in an emergency. Unfortunately, some vulnerable members of society do not have access to a cell phone, thereby removing perhaps their only connection to the assistance and support they need.

Valuable Partnership

To alleviate such barriers, the Jeffersontown, Kentucky, Police Department (JPD) established a partnership with the 911 Cell Phone Bank (CPB), a nonprofit that provides mobile devices to victims of abuse; senior citizens; and other vulnerable persons, such as homeless or transient individuals, in need at no cost. This program gives them a cell phone — theirs to keep — that includes a reloadable SIM card preloaded with 1GB of data, 1,000 minutes, and 1,000 text messages.

The CPB provides considerable support for the program. Departments are encouraged — but not required — by the nonprofit to hold an electronic device collection drive in the local community or donate any phones left behind in lost and found or in property and evidence rooms. Agencies receive boxes and prepaid shipping labels for returning the collected devices. The program is not based on a debit system; the CPB sends the number of phones needed, while the department collects what it can.

After receiving the phones, the CPB utilizes verification software to guarantee data erasure of all electronic devices according to federal guidelines.1 Those that cannot be erased are disassembled for parts and sent to a certified electronics recycler to reclaim precious metals, keeping landfills clear of e-waste.2 No formal paperwork is required, and the CPB takes full liability in the event of a data breach. The nonprofit can provide a department with any form of confirmation documentation that may be required, including receipts, itemized listings (make, model, and IMEI number),3 verifications of manifests, signed releases, and certifications of recycling or destruction.

Victims of Abuse

Intimate partner violence in the United States is rampant, affecting 1 in 4 women and nearly 1 in 10 men during their lifetime.4 The coronavirus pandemic sent victims into deeper isolation. During the height of the outbreak, JPD offense reports of intimate partner violence increased 69%, from 84 made between March and September 2019 to 142 during the same month span in 2021.

With the inability to seek help in person, many victims rely on their cell phones to connect with assistance and support. Unfortunately, that lifeline can be broken, monitored, or controlled by the abuser. If a phone is lost or destroyed, abusers often control finances to further manipulate victims, leaving it nearly impossible for them to purchase a new device or service.

While in the process of an investigation, an intimate partner victim must navigate a variety of challenging systems. The inability to reach quickly for their cell phone to make calls, contact family, and access information is a critical loss of assistance and communication. Nonetheless, many victims must face this reality every day, and it compounds the already overwhelming stress of dealing with trauma associated with the abuse. It also adds to the difficulties of facing an unfamiliar criminal justice system and the time-consuming task of trying to locate and obtain support services.

Senior Citizens

Over 7 million adults 65 and older have incomes that fall below the federal poverty level.5 With the rising costs of medical treatment, prescription medication, housing, and other bills, cell phone service is an expense that few senior citizens can afford but many cannot live without. Exacerbating their need, senior citizens often have complicated medical conditions that result in a need for emergency services. They are at elevated risk for falls, with about 36 million reported each year; more than 32,000 result in death.6 Often, these deaths result from prolonged periods without treatment.

“Unfortunately, some vulnerable members of society do not have access to a cell phone, thereby removing perhaps their only connection to the assistance and support they need.”

Distributing cell phones to senior citizens could save their lives. These devices not only provide seniors with a mechanism to call for an ambulance but also serve as an invaluable link to social support with family and friends, medication refills, medical appointment scheduling, and even the coordination of rides to the senior community center for socialization.

Homeless and Transient Persons

Investigating or aiding someone who is transient or experiencing homelessness is particularly challenging. If these individuals have no cell phone service, the challenges are insurmountable. Providing a homeless or transient individual with a device can increase their ability to participate in the criminal justice process.

While the provision of a cell phone can aid an investigation, the benefit to individuals and their quality of life is equally compelling and significant. A phone can help them find food, shelter, health care, mental health and substance abuse treatment, assistance with public transportation, and a wide range of other social services.

Benefits to the Agency

Whether creating a lifeline for a senior citizen, helping an intimate partner victim access services and rebuild a support network, or improving the quality of life of a homeless or transient person, access to cell phones creates quick solutions to problems that otherwise could feel insurmountable in the short term. Providing a device to community members — at no cost to them — helps remove one of the many barriers that an individual may face. It can also be an invaluable tool to maintain cooperation from victims whose cell phone was seized as evidence.

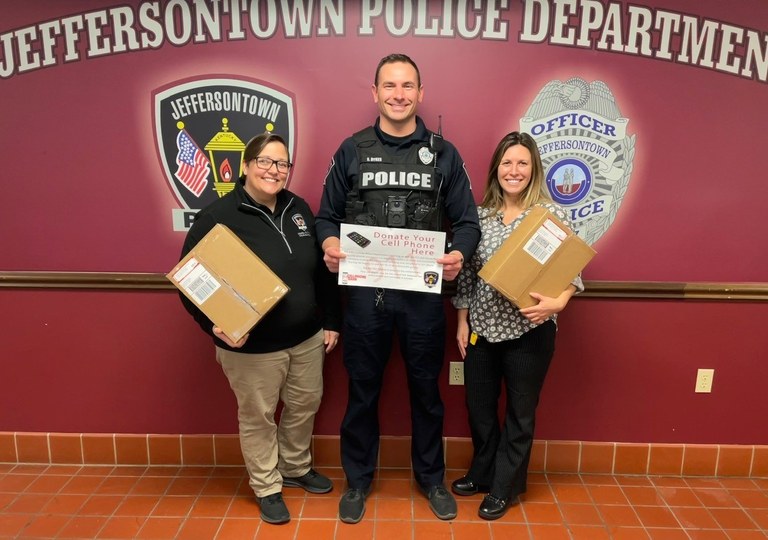

The JPD began a community drive to collect phones and within a week had collected over 70 to donate to the CPB. This led to another unanticipated benefit — the positive publicity that resulted in community awareness of an effective police program to assist victims. In addition, citizens contributed to the effort by donating unused devices. Phones collected in similar drives across the country will also see new life, helping Jeffersontown community members in the greatest need of access to a cell phone.

“The benefits of partnering with the 911 Cell Phone Bank are compelling for both victims and the agency.”

911 Cell Phone Bank

Phone: 866-290-7864

Email: requests@911cellphonebank.org

Web: https://www.911cellphonebank.org

Conclusion

The benefits of partnering with the 911 Cell Phone Bank are compelling for both victims and the agency. This program alleviates an added burden for the most vulnerable populations and provides them with a critical connection to services and support. And, departments will enjoy an enhanced image and improved relations with the community.

Ms. Chapman, a licensed clinical social worker, is the community resource supervisor for the Jeffersontown, Kentucky, Police Department. She can be reached at achapman@jtownkypd.org or 502-267-0503 ext. 399.

Endnotes

1 For additional information, see U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Guidelines for Media Sanitization, Richard Kissel et al., NIST Special Publication 800-88 Revision 1, December 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-88r1.

2 For additional information, see U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Certified Electronics Recyclers,” accessed March 2, 2022, https://www.epa.gov/smm-electronics/certified-electronics-recyclers.

3 For additional information, see “What to Understand About IMEI Numbers,” Verizon, accessed March 2, 2022, https://www.verizon.com/articles/what-to-know-when-buying-a-used-phone/.

4 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief — Updated Release, Sharon G. Smith et al. (Atlanta, 2018), 7, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf.

5 Juliette Cubanski et al., How Many Seniors Live in Poverty? (San Francisco: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018), https://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-How-Many-Seniors-Live-in-Poverty.

6 Briana Moreland, Ramakrishna Kakara, and Ankita Henry, “Trends in Nonfatal Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years — United States, 2012-2018,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69, no. 27 (July 2020): 875-881, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6927a5.