Workplace Violence Prevention

Readiness and Response

By Stephen J. Romano, M.A.; Micòl E. Levi-Minzi, M.A., M.S.; Eugene A. Rugala; and Vincent B. Van Hasselt, Ph.D.

Workplace violence, a complex and widespread issue, has received increased attention from the public, mental health experts, and law enforcement professionals.1 The wide range of acts that fall under this rubric include all violent behavior and threats of violence, as well as any conduct that can result in injury, damage property, induce a sense of fear, and otherwise impede the normal course of work.2 Threats, harassment, intimidation, bullying, stalking, intimate partner violence, physical or sexual assaults, and homicides fall within this category.3

Although a handful of high-profile incidents (e.g., mass shootings at a workplace) have led to increased public awareness, prevalence rates show that nonfatal workplace violence is a more common phenomenon than previously believed. For example, a Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report estimated that approximately 1.7 million incidents of workplace violence occurred each year between 1993 and 1999, with simple and aggravated assaults comprising the largest portion.4 The same report revealed that 6 percent of workplace violence involved rape, sexual assault, or homicide. According to a Bureau of Labor Statistics report, 518 homicides occurred in the workplace in the United States in 2008.5 Most recently, data revealed that 16 percent of workplace fatalities resulted from assaultive and violent acts.6 However, this being said, most workplace homicides take place during robberies or related crimes. Finally, considering actual reported workplace violence, it is estimated that these events cost the American workforce approximately $36 billion dollars per year.7

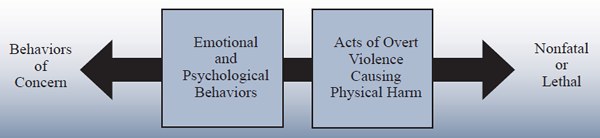

Recently, two of the authors, Rugala and Romano, conceptualized a workplace violence spectrum (adapted from the American Society for Industrial Security International) as a means of understanding and categorizing crimes that occur within the workplace.8 As illustrated in figure 1, the right end of the spectrum consists of such acts as overt violence causing physical harm, nonfatal assaults with or without weapons, and lethal violence. Moving toward the left end of the spectrum, behaviors become less physical and more emotional/psychological. These include disruptive, aggressive, hostile, or emotionally abusive conduct that interrupts the flow of the workplace and causes employees concern for their personal safety. Bullying, stalking, and threatening appear on this end of the spectrum. At the far left end are behaviors of concern. According to Rugala and Romano as well as others, individuals do not “snap” and suddenly become violent without an antecedent or perceived provocation.9 Instead, the path to violence is an evolutionary one often consisting of such behaviors of concern as brooding and odd writings or drawings. These can be subtle indicators of the potential for violence and may be unusual or typical for an individual.

Several typologies of workplace violence behaviors and events also have emerged over the past few years.10 Rugala divides workplace violence into four types, or categories, of acts based on the relationship among victims, perpetrators, and work settings (see figure 2).11 Type I incidents involve offenders who have no relationship with either the victims or the establishments. Type II events are those where the offenders currently receive services from the facilities (retail-, health-, or service-industry settings) when they commit an act of violence against them. Type III episodes involve those current or former employees acting out toward their present or past places of employment. In Type IV situations, domestic disputes between an employee and the perpetrator spill over into the workplace.

Prevention

Many corporations and organizations throughout the United States have instituted programs to help prevent violence in the workplace. These efforts can go a long way toward mitigating the threat of such occurrences. Although no extant actuarial methods for predicting workplace violence exist, employees can take certain actions to reduce these incidents. First, it is critical to understand that workplace violence does not happen at random or “out of the blue.” Rather, perpetrators usually display some behaviors of concern. Thus, awareness of these indicators and the subsequent implementation of an action plan to de-escalate potentially violent situations form essential components of workplace violence prevention.

Behaviors of concern can help workers recognize potential problems with fellow employees. If a coworker begins acting differently, determining the frequency, duration, and intensity of the new, and possibly troubling, behavior can prove helpful. Specific behaviors of concern that should increase vigilance for coworkers and supervisors include sadness, depression, threats, menacing or erratic behavior, aggressive outbursts, references to weaponry, verbal abuse, inability to handle criticism, hypersensitivity to perceived slights, and offensive commentary or jokes referring to violence. These behaviors—when observed in clusters and coupled with diminished work performance (as manifested by increased tardiness or absences, poor coworker relations, and decreased productivity)—may suggest a heightened violence potential. It must be pointed out, however, that no single behavior is more suggestive of violence than another. All actions have to be judged in the proper context and in totality to determine the potential for violence.

Not surprisingly, relationship problems (e.g., emotional/psychological or physical abuse, separation, or divorce) can carry over from home to the work setting.12 Certain signs that may help determine if a coworker is experiencing such difficulties include disruptive phone calls and e-mails, anxiety, poor concentration, unexplained bruises or injuries, frequent absences and tardiness, use of unplanned personal time, and disruptive visits from current or former partners. Care must be taken when dealing with what can be highly charged situations. Companies may lack the expertise to handle these on their own and may have to consult with experienced professionals. Finally, all incidents are different and must be viewed on their own individual merits. Experience has shown that no “one size fits all” strategy exists.

Intervention

Intervention strategies must take into account two aspects of the workplace violence spectrum: action and flash points. An action point is the moment when an individual recognizes that an employee may be on the path toward committing some type of violent act in the workplace and subsequently takes action to prevent it. Action points offer an opportunity for coworkers to intervene before a situation becomes dangerous. Given that human behavior is not always predictable and that no absolute way exists to gauge where an individual may be on the pathway, spectrum, or continuum toward violence, action points should be established as early as possible.

Mr. Romano, a retired FBI special agent, operates a consulting/ training firm in Greenville, South Carolina.

Ms. Levi-Minzi is a doctoral student at the Center for Psychological Studies, Nova Southeastern University, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Mr. Rugala, a retired FBI special agent, is with the Center for Personal Protection and Safety in Spokane, Washington.

Dr. Van Hasselt is a professor of psychology at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and a police officer in Plantation, Florida.

When an action point has been identified, fellow employees can intervene in a number of ways. First, they can talk with the person and “check in” to see if everything is all right. Allowing people to vent about stressful life situations can help them release tension.13 This type of intervention should be used cautiously. If the individuals display potentially threatening behaviors of concern, vigilant coworkers should report these directly to a supervisor. Workers also can relay information regarding questionable behaviors to their human resources or security department, ombudsman, or employee assistance program. Moreover, if employees feel unable to directly approach someone about a coworker, they can communicate their concerns via an e-mail or text message. Companies have used drop boxes, 24-7 tip lines, and ethics hotlines to allow employees to report suspicious behavior while maintaining their anonymity.

| Type of Act | Description of Act |

| Type I | Offender has no relationship with the victim or workplace establishment. In these incidents, the motive most often is robbery or another type of crime. |

| Type II | Offender currently receives services from the workplace, often as a customer, client, patient, student, or other type of consumer. |

| Type III | Offender is either a current or former employee who is acting out toward coworkers, managers, or supervisors. |

| Type IV | Offender is not employed at the workplace, but has a personal relationship with an employee. Often, these incidents are due to domestic disagreements between an employee and the offender. |

A “flash point,” the moment when workplace violence occurs, is too late for any type of preventive strategy and best avoided by implementing initiatives early, once an action point has been detected. After a flash point, coworkers often indicate that they were concerned about the offender but never reported their suspicions. Consequently, authorities emphasize that “if you sense something, say something.” Employees generally do not want to be viewed as undermining their peers and, therefore, wait until they are certain that a situation is serious before reporting it. Unfortunately, at this point, it may be too late. This stresses the importance of awareness on the part of employees. Workers must be trained so that when behaviors of concern occur, a “red flag” is raised and appropriate action taken. In this strategy, awareness + action = prevention constitutes the key to prevention. By being aware of and acting on behaviors of concern, employees can help keep their workplace safe from violence. Most important, companies must create a climate of trust within their organizations that allows their employees to come forward to report troubling behavior.

Survival

An awareness of the workplace violence spectrum, along with knowledge of prevention and intervention strategies, can help increase safety in the work setting. However, advance planning and preparation for such incidents and knowing how to respond if one occurs are imperative for survival. Of equal importance is recognizing the difference between an active-shooter scenario and a hostage situation because of the different approaches needed in each set of circumstances.

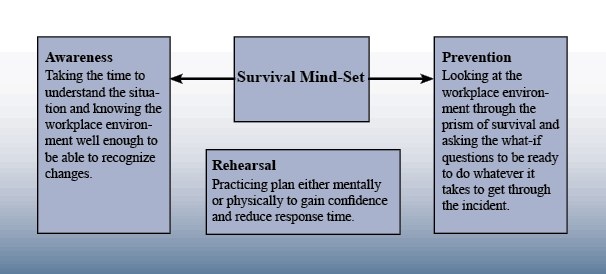

In a more personal vein, realizing that the incident may end prior to the arrival of law enforcement demonstrates the need for workers to take responsibility for their own lives, in part, by developing a survival mind-set, which involves being ready (both mentally and physically) for the worst-case scenario. While no foolproof strategy for surviving an active-shooting incident exists, this type of mind-set has the three components of awareness, preparation, and rehearsal which can provide a foundation for survival (see figure 3).14 Awareness means understanding that workplace violence can impact anyone, in any work setting, and across all levels of employment. Further, awareness involves knowing the work environment well enough to recognize when changes occur that may reflect a potential problem. While some may be subtle (e.g., verbal outbursts), others are more obvious (e.g., gunshots).

The second component of the survival mind-set, preparation, entails employees becoming stakeholders in their own safety and security. In particular, they must change how they view their work environment and shift to a what-if way of thinking. For example, workers must consider what they would do if an active shooter was in the hallway or lobby of their office building. These types of scenarios will help them plan and be better prepared for a possible workplace violence incident.

The third element of the survival mind-set involves rehearsing for an event. This may include a mental rehearsal or a walk-through of the workplace to determine possible exit routes or hiding places. This can help inoculate employees against the stress of survival, reduce their response time, and build confidence in their ability to survive. This idea is akin to that of fire drills and role-playing, which involve simulations of real-world situations to teach new behavioral skills.15 Indeed, practicing responses in advance produces a more fluid and rapid response in the event of a real incident.

Responses

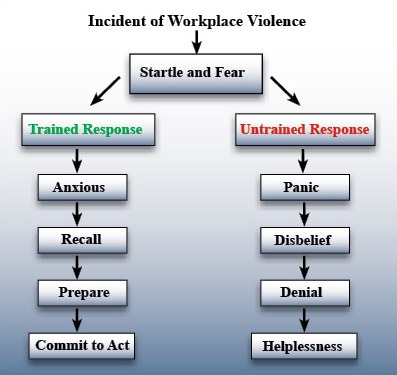

Figure 4 illustrates the disparities in responses between those who have and those who have not been trained to deal with these types of stressful situations. Both groups initially react by being startled and experiencing fear. Then, they begin to diverge: the untrained panic, whereas the trained experience controllable anxiety. From that point on, the trained group members begin to recall what they should do next, prepare, and act. The untrained, however, experience disbelief that eventually leads to denial and, ultimately, helplessness. Knowing how differently the groups will react based solely on training underscores the importance of advanced preparation.16

The first response to an active-shooter incident is to figure out what is occurring. For example, Hollywood has simulated gunshots in countless movies and television shows; however, real gunfire sounds extremely different. Rapidly assessing the situation and evaluating available options constitute the first steps toward survival. This may include evacuating the building; however, sometimes the only alternative is concealment. The process of assessing the situation and evaluating options will cycle continuously through the minds of workers over the course of the event.

This type of assessment may point to the possibility of escape. In that case, employees should leave as quickly as possible, without seeking approval from others or waiting to collect belongings. Once safe, they should immediately contact emergency personnel. In these situations, phone lines often become jammed, or individuals may think others have contacted authorities when, in reality, no one has called for help. Once connected to an emergency operator, certain information, if known, should be relayed: description and location of the perpetrator, number and types of weapons used, and an estimate of the number of people in the building.

“Awareness means understanding that workplace violence can impact anyone, in any work setting, and across all levels of employment.”

If escape is not feasible, employees can take other actions. For example, finding a hiding place can mean the difference between life and death. If an office space is available, workers can lock themselves in, barricade the door, and become very quiet so as not to alert the perpetrator. Individuals gathered together should disperse because it is easier to inflict a greater number of casualties when shooting at a group or cluster of people; therefore, spreading out will create confusion and provide fewer targets, resulting in fewer victims. Another critical action is ongoing communication with fellow employees. Keeping everyone informed of the situation and helping the injured are important to surviving an active-shooter event.

Although escaping or hiding from danger are solid survival strategies, they may not always be possible. The shooter may directly confront workers. When this occurs, they must be prepared to know what they have to do and understand that neutralizing the shooter in some manner may be their only way to survive. This involves behaviors and a mind-set that few people ever have to consider. Coming to terms with what needs to be done and then committing to it will prove necessary and likely mean the difference between life and death.

Situations

Active-shooter and hostage situations are equally dangerous; both present a high risk for injury or death. However, it is imperative to know the difference between them (see figure 5).

from an individual to a group, active shooters operate in close quarters or distant settings, choosing random or specific targets. Hostage takers also are armed and dangerous individuals who may or may not use deadly force.17 But, one main difference is that an active shooter may have unrestricted access to victims, whereas a hostage taker is restricted either by choice or the presence of law enforcement. Hostage takers and their captives often are contained in a specific space and surrounded by law enforcement until the situation is resolved.

| Type of Perpetrator | Description of Perpetrator |

| Active Shooter | An individual with a firearm who begins shooting in the workplace. |

| Hostage Taker | An armed individual who may or may not use deadly force, has restricted access to victims, and eventually will be contained with hostages. This type of perpetrator is motivated in one of two ways.

|

Moreover, hostage takers differ in that they subscribe to either substantive or expressive motives.18 Substantive motives involve money, material items, escape, and social or political change that hostage takers cannot obtain on their own. Perpetrators with expressive motives are compensating for a loss (e.g., end of a relationship or job) and appear irrational because their actions are emotionally driven. The motives of hostage takers generally do not include harming captives because this would completely change the situation and the consequences.19 Those who operate based on substantive motives do not want to harm their captives because they need them as pawns to achieve their goals.

It is important for individuals held captive to remember that it will take law enforcement negotiators time to resolve the situation. Patience on their part is essential for survival. Some recommended strategies include remaining calm, following directions, and not being argumentative or irritating to the perpetrator. Further, it is critical for captives to find a “neutral ground” where they are neither too assertive nor too passive with their captor.20

Although negotiating to end the hostage-taking scenario is preferable, sometimes law enforcement must neutralize the perpetrator. Police may use SWAT, active-shooter, or rapid-deployment teams.21 If this is the case, captives should take certain actions and avoid others to help law enforcement safely and efficiently resolve the situation. For example, when responding law enforcement officers arrive, they are not initially aware of the identity of the perpetrator. Also, their only goal is to neutralize or stabilize the situation. Police officers are taught that hands kill. Therefore, it is important for victims to raise their arms, spread their fingers, and drop to the floor while showing that they do not have any weapons or intention of harming anyone. Finally, once they have made contact with officers, survivors should relay any information that may help, such as how many shooters were present, identities and location of them, and weapons used.

Conclusion

Workplace violence is a prevalent and complex problem. While certain high-profile, catastrophic incidents have drawn the attention of the media and the public, numerous events go unreported. Workers should learn about workplace violence, recognize the behaviors of concern, and remember that awareness + action = prevention. If an incident does occur, they should be able to distinguish a hostage taker from an active shooter so that they can determine how to behave to increase their chances of survival.

Research has shown that many of these situations are over in minutes and law enforcement may not arrive in time. As a result, employees have to become stakeholders in their own safety and security and develop a survival mind-set comprised of awareness, preparation, and rehearsal. Vigorous prevention programs, timely intervention, and appropriate responses by organizations and their employees will contribute significantly to a safe and secure work environment.

Endnotes

1 R. Borum, R. Fein, B. Vossekuil, and J. Berglund, “Threat Assessment: Defining an Approach for Evaluating Risk of Targeted Violence,” Behavioral Sciences and the Law 17 (1999): 323-337; E.A. Rugala, U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Critical Incident Response Group, National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, Workplace Violence: Issues in Response (Quantico, VA, 2004); and M.D. Southerland, P.A. Collins, and K.E. Scarborough, Workplace Violence: A Continuum from Threat to Death (Cincinnati, OH: Anderson, 1997).

2 E.A. Rugala and J.R. Fitzgerald, “Workplace Violence: From Threat to Intervention,” Clinics in Occupational and Environmental Medicine 3 (2003): 775-789.

3 B. Booth, G. Vecchi, E. Finney, V. Van Hasselt, and S. Romano, “Captive-Taking Incidents in the Context of Workplace Violence: Descriptive Analysis and Case Examples,” Victims and Offenders 4 (2009): 76-92.

4 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Violence in the Workplace, 1993-99 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2001).

5 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Fatal Occupational Injuries from Transportation Incidents and Homicides (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2008).

6 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Charts, 1992-2008 (preliminary data) (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2009).

7 U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Violence in the Workplace, 1993-99.

8 American Society for Industrial Security, Workplace Violence Prevention and Response Guideline (Alexandria, VA: ASIS International, 2005).

9 J.C. Campbell, ed., Assessing Dangerousness: Violence by Sexual Offenders, Batterers, and Child Abusers (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995); and J.R. Meloy, Violence Risk and Threat Assessment: A Practical Guide for Mental Health and Criminal Justice Professionals (San Diego, CA: Specialized Training Services, 2000).

10 S. Albrecht, Crisis Management for Corporate Self-Defense (New York, NY: Amazon, 1996); R. Denenberg and M. Braverman, The Violence-Prone Workplace: A New Approach to Dealing with Hostile, Threatening and Uncivil Behavior (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999); and G.R. Vanderbos and E.Q. Bulatao, eds., Violence on the Job: Identifying Risks and Developing Solutions (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996).

11 E.A. Rugala, Workplace Violence: Issues in Response.

12 Booth, Vecchi, Finney, Van Hasselt, and Romano, “Captive-Taking Incidents in the Context of Workplace Violence: Descriptive Analysis and Case Examples”; and G.M. Vecchi, V.B. Van Hasselt, and S.J. Romano, “Crisis (Hostage) Negotiation: Current Strategies and Issues in High-Risk Conflict Resolution,” Aggression and Violent Behavior: A Review Journal 10 (2005): 533-551.

13 R.K. James and B.E. Gilliland, Crisis Intervention Strategies, 4th ed. (Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, 2001).

14 S.J. Romano and E.A. Rugala, Workplace Violence: Mind-Set of Awareness (Spokane, WA: Center for Personal Protection and Safety, 2008).

15 M.E. Levi-Minzi, S.L. Browning, and V.B. Van Hasselt, “Role-Playing as a Measure of Program Effectiveness,” in The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology (New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell, in press); and V.B. Van Hasselt and S.J. Romano, “Role-Playing: A Vital Tool in Crisis Negotiation Skills Training,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, February 2004, 12-17.

16 Van Hasselt and Romano, “Role-Playing: A Vital Tool in Crisis Negotiation Skills Training.”

17 S.J. Romano and M.F. McMann, eds., U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Critical Incident Response Group, Crisis Negotiation Unit, Crisis Negotiations: A Compendium (Quantico, VA, 1997); and Vecchi, Van Hasselt, and Romano, “Crisis (Hostage) Negotiation: Current Strategies and Issues in High-Risk Conflict Resolution.”

18 G.W. Noesner and J.T. Dolan, “First Responder Negotiation Training,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, August 1992, 1-4; and S.J. Romano and E.A. Rugala, Workplace Violence: Survival Mind-Set (Spokane, WA: Center for Personal Protection and Safety, 2008).

19 Romano and Rugala, Workplace Violence: Survival Mind-Set.

20 Ibid.

21 T.L. Jones, SWAT Leadership and Tactical Planning: The SWAT Operator’s Guide to Law Enforcement (Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 1996).