From the Archives

Police Operations During a Natural Disaster (June 1971)

By Howard L. Hobbs

Hurricane Camille is said to have been the worst storm ever to hit the mainland of the United States. With winds in excess of 200 miles per hour and tidal waves over 20 feet, Camille smashed into the Mississippi Gulf Coast on Sunday night, August 17, 1969.

Several times each year the southeast coast of the United States is struck by hurricanes. Born over the warm seas of the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, these large cyclonic systems result from a peculiar blend of heat, winds, atmospheric pressure, and moisture. Anywhere from 100 to 800 miles across, they rage north toward Cuba or Florida, assaulting everything in their path. Usually, however, they turn out to sea or dissipate before they do too much damage. Only one out of four hits the United States mainland. Since 1953 they have been given women’s names, such as Hannah, Dora, and Flora.

On August 17, 1969, a Caribbean-born hurricane with the gentle name of Camille roared into the area of Gulfport, Miss., located directly on the Gulf of Mexico between Mobile, Ala., and New Orleans, La. Carrying tides as high as 23 feet and pushed by 210-mile-per-hour winds, the storm brought death, destruction, and misery. It also set records for being the strongest hurricane on record. The head of the National Hurricane Center in Miami, Fla., said that Camille was “the greatest storm of any kind that has ever affected this Nation, by any yardstick you want to measure with.”1

Camille blew harder than any other hurricane recorded and the barometer dropped to 26.61 inches, the lowest since a 1935 Florida hurricane.2

As the hurricane approached the Mississippi Gulf Coast on August 17th, the manager of the local television station went on the air and repeatedly warned residents of the beach-front area and low-lying locations to evacuate their homes and seek shelter elsewhere. Estimates of as many as 50,000 people leaving the coast have been given by different sources. However, no estimate can be made of the number of lives saved by heeding the television warnings. As a result of his actions, the manager was awarded a good Samaritan award by a national association in 1970.

Many citizens had ridden out the 1947 hurricane which had struck the Gulf Coast, and a lot of them believed that Camille could not possibly be worse than the terrible storm of 22 years ago. That storm had contained a tide of 12 feet above sea level and winds of 125 miles per hour.3 The area was severely damaged at that time, and even though storms were not then named, no one has since forgotten it. As Camille approached, the community boarded up and began the tense waiting period before the arrival of the terrible winds and tides.

Howard L. Hobbs, Chief of Police, Gulfport, Miss.

At 7 p.m. the winds had reached gale force; at 8 p.m. the tides were rising rapidly and were being pushed by hurricane force winds. By 11 p.m. the winds had reached an unbelievable 200 miles per hour with 20-foot waves battering the mainland. The wind can best be described as sounding like a locomotive going by a few feet away. All power failed when the winds reached their peak strength. The police department’s electrical generator operated a short while and then it too failed. Around 11 p.m. the eye of the storm raged inland just east of Gulfport. As it passed by, the rapid drop in the barometric pressure caused sharp pains in everyone’s eardrums. With the passing of the eye, the winds reversed direction and maintained their ferocious velocity. Finally, at approximately 2 a.m. on the morning of August 18th, the winds started to abate slightly and the sea started receding. By 4 a.m. the winds had stopped altogether.

Severe Destruction

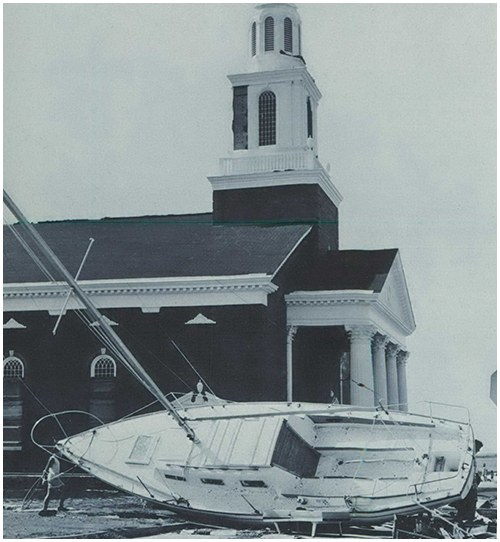

At daybreak the death and destruction were unbelievable to even the experienced residents who had seen many hurricanes in the past. Three ocean-going freighters had been tossed ashore as if they were toys, the entire downtown business district was in shambles, and the beachfront was virtually destroyed. All of the Gulf Coast was without fresh water, power, and natural gas. The total destruction of miles and miles of homes and buildings cannot be described by pictures or words. The stench of death was everywhere; bodies were found hanging in trees, mingled in the debris, and floating in the cluttered waters of the gulf. The garages of two funeral homes were used to temporarily store bodies of victims until identification could be made. In some instances bodies were found to have been previously embalmed. It was then discovered that a cemetery had been washed open by the rush of water which then deposited the embalmed bodies at another location far removed from the burial sites.

Statistics

Several months after the storm Red Cross statistics showed that on the Gulf Coast Camille killed 145 persons, 22 were still missing, 10,054 were injured with 73,857 families affected. As to damage, 5,652 homes were destroyed, 13,915 homes had major damage, 33,933 homes had minor damage, 1,082 mobile homes were destroyed, and 621 had major damage.4 The Office of Emergency Preparedness has set the figure for the amount of actual physical damage at $950 million.5

All of the hospitals on the coast were damaged to the extent that a majority of them had to evacuate their patients to hospitals in other areas. The small city of Pass Christian, Miss., was so badly damaged that Gov. John Bell Williams ordered the forced evacuation of the entire town of 3,000 persons because of the health hazard posed there. The residents were bused to a National Guard installation at Camp Shelby, Miss.6

Communications with the outside world were severely hampered because over 80,000 telephones were out, power was off, and most news agencies could not function. A radio station went off the air while broadcasting during the height of the storm when its antenna fell on top of the transmitting office. Two station personnel narrowly escaped death when the building was demolished by the steel tower.

The Gulfport police headquarters and jail facilities were severely damaged; three patrol cars were total losses; and all power, natural gas, and water services were out. All personnel of the department were exhausted from the all-night ordeal; the men held in reserve for depth of coverage were unable to rest during the long night and therefore were just as tired as the on-duty officers. Five members of the force lost everything they owned as a result of the wind and water. All that remained of several of the officers’ homes were the concrete front steps.

Surveying the Damage

Survivors were found everywhere, usually stumbling around in debris that hours before had been their homes. Police patrols were kept constantly busy transporting victims to shelters for medical treatment and temporary living quarters. Our department’s doctor stayed on duty for several days without rest and was credited with treating over 1,000 patients that officers brought in.

A majority of the streets were impassable because of either debris or physical damage to the road surfaces. The streets that were passable were littered with roofing nails that had been blown from the roofs of thousands of damaged or destroyed homes. Flat tires on police patrol units because a serious problem; some had as many as three flat tires at one time.

In the Pass Christian, Mississippi, area, two of the four lanes of U.S. Highway 90 were severely damaged.

The storm grounded three ocean freighters on the north side of the Gulfport harbor.

A barge pushed onto U.S. Highway 90 by the winds and high tides was refloated by means of a dike lined with plastic.

Gulfport’s new recreational center had been open less than a month when Camille reduced it to shambles.

The Highway Patrol and the Chamber of Commerce quickly moved in house trailers to use as offices after the storm.

Destruction was so severe and widespread over the entire Gulf Coast that police departments in the area could not possibly provide security for public or private property. The Governor quickly proclaimed a semi-martial-law situation which enabled him to call out the Mississippi National Guard to provide security guards and patrols 24 hours a day. The downtown business area was cordoned off by the Guard, and no one was allowed to enter the area unless he had first obtained a written pass from the police department.

The pass system caused police headquarters to be jammed with long lines of business people and employees waiting to identify themselves and obtain passes from the administrative officer. This security method caused many problems and delays. However, unlike police officers who generally knew the downtown merchants and clerks, the National Guardsmen did not know anyone and therefore a system of identification was necessary.

Getting Organized

At sundown each day the city was truly dark, with only an occasional light or lamp to be seen in entire neighborhoods. A curfew was imposed and no one was allowed on the streets after dark except police or emergency workers. Anyone else had to obtain a pass to travel at night. This was necessary to keep down looting and make security easier. Looters operating on foot at night were a problem because the area was in complete darkness and the mountains of debris afforded numerous hiding places.

Service stations could not pump gasoline without power; however, some enterprising operators hooked up various gasoline-driven devices to their pumps and got back into business. The U.S. Navy Seabees rushed a large generator to the police department and soon had the power back on. This enabled the restoration of the department’s gasoline pump which then serviced all emergency vehicles operating in the city.

Over the years law enforcement has met obligations to the public by planning translated into action. In the area of unusual occurrences, however, as other police departments have found, there is a lack of published information.7 At the time Camille struck, no formal written plan of police action was in effect. The usual practice was to handle the problems as they occurred with very little preparation beforehand. This disaster has shown us that we must have a written plan of action that is broad in scope and flexible in operation. Experiences gained in a storm of this magnitude have given us much to work with in mapping out a plan of action for future disasters. Our written plan contains the following basic ideas that can be expanded or adapted to suit the needs of almost any agency.

I. Organizational Structure

A. The Department’s organizational structure must be realigned to meet the changing situation. It must be changed to utilize personnel to provide:

1. Staff with depth.

2. Maximum line services.

3. Liaison services.

4. Supplies and auxiliary services.

Along with the realigned organizational structure, the new job assignments for all personnel must include written job descriptions with duties and responsibilities clearly defined. This is absolutely necessary in order to prevent duplication and improve efficiency.

B. The usual staff structure will be changed to handle the priorities that the situation has brought about. Staff officers who normally are in the detective, traffic, and identification division are to be reassigned to liaison, line, and auxiliary services.

II. Equipment

A. A detailed list of all equipment owned by the department will be maintained under this section. This will include vehicles, radios, flashlights, generators, tools, supplies, foul weather gear, etc. In the rush and excitement of disasters, many pieces of equipment in possession of the department have been overlooked and forgotten.

B. An inventory checkout system must be instituted and kept up to date on all equipment to insure that all articles are getting maximum utilization.

C. A list of equipment owned by other public-service-type agencies in the city will also be included in the plan. Fire, civil defense, and public works departments maintain large aggregates of equipment needed during emergencies. Knowing what equipment is available and where it is located is a valuable asset and can save a lot of time and work. In an emergency operation center where representatives of each of the above-mentioned agencies would be present, the list of equipment would still be valuable. In these types of operations, the police executive is normally the person to whom the requests for material are directed, and therefore he should be familiar with the location of needed items.

D. Assistance by private industry and individuals. Privately owned mobile radio units are an asset not be overlooked. Our plan will include a resume of vehicles that are available to the department. This will include heavy equipment, cars, trucks, and specialized items such as trucks with generating plants attached. During Camille many citizens volunteered mobile radio units that greatly relieved patrol units for emergency assignments. Working agreements should be thoroughly discussed with all parties concerned with respect to these vehicles. Instructions on whom to see and what to do in order to secure the operation, use, or loan of the these items, plus any restrictions or stipulations, should be in writing in the plan.

III. An emergency operations center is a desirable item in a disaster plan. We are constructing one in a house trailer obtained from the Gulfport Housing Authority and have requested a Justice Department grant for purchase of the equipment to be installed in the center. The trailer will contain:

A. Staff office.

B. Telephone switchboard.

C. Radios for city, county, State, and public works departments along with a collapsible antenna for mobility.

D. Overhead projectors which will show current situations and maps of the area of concern.

E. Air conditioning and a kitchen. A large generator on another trailer will be kept with the center.

The mobility of the center will allow us to move our operation, if necessary, right to the scene of problem areas. This would be true only in smaller disasters, however. A storm the size of Camille would require that the trailer be utilized as a center of all police operations and liaison with other agencies.

Since Hurricane Camille, the Gulfport Police Department has constructed a complete new complex of buildings located farther away from the beach area. On April 1, 1970, we moved into the new buildings which were constructed in record time. While the city had lost most of its tax structure from all the destroyed homes, the construction of the police facilities was started soon after the storm. This was possible because business firms in the area donated a majority of the materials and supplies used in the project. Officers of the force who were skilled in building trades furnished the labor.

With our new buildings, equipment, and hard-earned experience from that terrible night in August 1969, we feel that we are now in a position to better serve the citizens of our community should another Camille decide to visit the Mississippi Gulf Coast. We just hope that we do not have to put our planning into action anytime in the near future.

Endnotes

1 “Killer Camille: The Greatest Storm,” Time Magazine, vol. 94, No. 9, Aug. 29, 1969, p. 20.

2 Ibid.

3 H.C. Sumner, “North Atlantic Hurricanes & Tropical Disturbances of 1947,” Monthly Weather Review, vol. 75, No. 12, Dec. 1947, p. 251.

4 “Hurricane Camille,” Nursing and Medical Task Force Action, The American National Red Cross, Dec. 31, 1969.

5 The Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, Aug. 17, 1970.

6 “A Killer Named Camille and Her Toll,” Newsweek Magazine, vol. 74, Sept. 1, 1969, p. 18.

7 Henry H. Bertch, Jr., “Police Participation in Disaster Control,” Police Research and Development Institute, Apr. 21, 1965, p. 1.

From the Archives is a new department that features articles previously published throughout the 80-year history of the Bulletin. Topics include crime problems, police strategies, community issues, and personnel, among others. A link to an electronic version of the full issue will appear at the end of each article.