Officer Survival Spotlight

Circumstances and the Deadly Mix

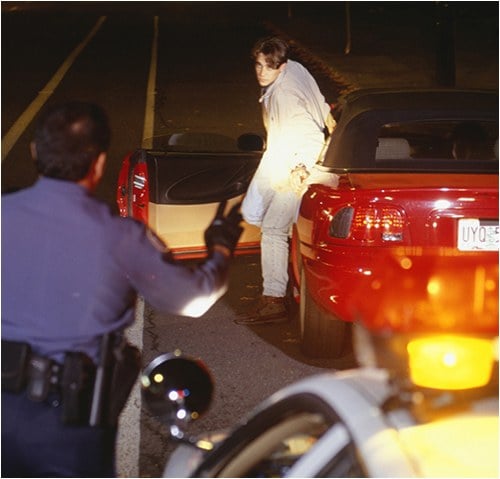

In a large city on a weekday morning at 4 a.m., an officer with five years of law enforcement experience is on patrol. The officer also has a civilian—commonly referred to as a “ride along”—with her. A citizen stops the officer and reports a stolen car. Not long after broadcasting the reported theft, the officer observes an automobile matching the description of the stolen vehicle. The car is occupied by two males and one female. The officer executes a traffic stop, and immediately a male subject exits the vehicle and attempts to walk away. The officer detains the subject, asks for identification, and conducts a frisk search. During the frisk the officer finds a concealed knife. She secures the weapon, notifies dispatch of her situation, and starts to take the subject into custody.

When the officer attempts to make the lawful arrest, the subject turns and tries to disarm her. A life-or-death struggle for the officer’s weapon ensues. The assailant wrestles the officer to the ground, and having no success in obtaining the weapon, he instructs the female perpetrator to retrieve a handgun from the stolen vehicle. The female subject complies and gives the assailant the weapon as both the officer and the perpetrator get to their feet. The officer now is facing a drawn weapon, three subjects, an unarmed ride along behind her, and the assailant threatening to kill her if she did not surrender her service weapon. She draws her weapon and is shot in her left arm, but is able to fire four rounds, with all four on target striking the perpetrator in the abdomen, pelvis, and leg. The subjects flee the scene and later are apprehended when the assailant is unable to continue due to the severity of his wounds. The officer returns to full duty 4 weeks after the incident.1

The Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program conducted three groundbreaking studies: Killed in the Line of Duty, In the Line of Fire, and Violent Encounters. The culmination of the trilogy, Violent Encounters, examined the “deadly mix” theory. During law enforcement contacts, there is an officer, an offender, and the circumstances that brought them together. When these variables come into contact with one another, this is referred to as the deadly mix.2 How officers handle this mix could mitigate their chances of critical injury.

Using the case study, this article focuses on the circumstances of the deadly mix. Circumstances include whether an officer was dispatched or initiated the contact, time, location, method of arrival, other individuals involved, and weapons used.3 When an officer is not forced to take immediate law enforcement action, a quick analysis of the known circumstances should be conducted. Officers should decide if the circumstances provide a favorable outcome for them or for the offender. LEOKA instructors refer to this as analyzing the “power curve.” Officers should ask themselves if the power curve is in their favor, and if not, what can be done to change it.

Mr. James J. Sheets is a former police lieutenant and an officer safety awareness training instructor with the FBI’s Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted Program.

In this case study the officer was not forced to take immediate action. The officer noted seeing the three suspects in the vehicle before initiating the traffic stop. A quick analysis of the known circumstances she faced indicated that she was outnumbered 3 to 1 and had the added responsibility of having an unarmed civilian ride along. The officer was behind the power curve. Time was on the side of the officer in this incident. The situation did not require immediate law enforcement response. Some options were available, such as requesting back up and following the vehicle, while waiting for more law enforcement personnel to arrive before initiating the traffic stop.4 These factors would have changed the circumstances and brought the power curve into the officer’s favor.

Police officers are trained to apprehend the perpetrators of crimes. Because of this, officers sometimes rush into situations without fully appreciating the circumstances facing them.5 It is understood that are times when law enforcement procedures require an officer to immediately intervene. The research makes it clear. “The circumstances did not cause the assaults, but, rather, contributed to them.”6 Training should include scenario-based incidents where officers have time to analyze the circumstances and make decisions.7 The research also suggests that officers who make decisions that bring the power curve to their favor are controlling the deadly mix, thus, enhancing officer safety, mitigating critical injury, and possibly saving lives.8

Endnotes

1 A.J. Pinizzotto, E.F. Davis, and C.E. Miller III, U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, In the Line of Fire: Violence Against Law Enforcement (Clarksburg, WV, 1997).

2 A.J. Pinizzotto, E.F. Davis, and C.E. Miller III, U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Violent Encounters: A Study of Felonious Assaults on Our Nation’s Law Enforcement Officers (Clarksburg, WV, 2006).

3 Ibid.

4 Pinizzotto, Davis, and Miller, In the Line of Fire; and Pinizzotto, Davis, and Miller, Violent Encounters.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.