Officer Survival Spotlight

What Is a Safe Distance?

Law enforcement personnel face real-life dangers every minute, every hour, and every day while protecting and serving their communities throughout the United States.

One spring evening a uniformed police sergeant, accompanied by a teenage cadet, responded to a call regarding a shoplifter—detained by security—at a large retail store. Upon arrival, the officer arrested the woman for a felony warrant and theft offense and learned from the security guards that her boyfriend waited outside.

The sergeant secured the female in the backseat of the marked patrol unit, and the man, approximately 15 to 20 feet away, confronted him in the darkened parking lot. Wearing a bulky jacket, the subject concealed his hands in the pockets. As the boyfriend approached, the officer commanded him twice—with no compliance—to show his hands.

He told the officer that he had a knife. The subject began to remove his left hand from his pocket, and the sergeant closed the distance between them to control the fixed-blade knife concealed in the jacket. As the officer took the offender’s left hand and the knife, the boyfriend used his other hand to remove a .38-caliber five-shot revolver from his right jacket pocket and shot the sergeant once in the head, right arm, and left front torso and twice in the back.

The officer sustained five gunshot wounds from a distance of less than 5 feet, but ultimately survived the attack. During the incident, the offender stabbed one of the security guards—who attempted to protect the sergeant—in the left side of his chest and shoulder area. The security guard also recovered after the incident.1

Analysis

This case study presents a dangerous close-distance encounter between a law enforcement officer and offender. In this situation, a sergeant and security guard suffered life-threatening injuries and were fortunate to survive.

Mr. Young is an instructor with the FBI’s Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted Program.

After his recovery, the police officer noted elements about the incident from which he narrowly escaped death.2

- As the event unfolded, the officer did not know the offender’s name, background, or extensive criminal history. Follow-up investigation identified the man as a violent gang member wanted for a felony offense.

- In addition to the knife and gun, the subject also possessed five improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

- The sergeant did not use distance, cover, or backup officers as a tactical advantage. Additional personnel were not requested until after the shooting.

While several issues in this encounter warrant extra consideration, the author will explore the proximity of the officer to the offender as an important facet.

Data

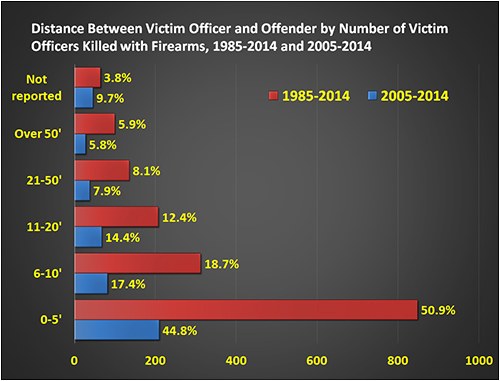

Statistics published annually by the FBI’s Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program suggest that in incidents involving firearms, close-distance encounters feature more officers killed by an offender compared with situations involving greater distances. Over a 10-year period between 2005 and 2014, 62.2 percent of officers murdered with firearms in the line of duty were shot within 0 to 10 feet of perpetrators. Of those incidents, 44.8 percent included events where offenders within 0 to 5 feet killed officers with firearms.3

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division (CJIS), Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program, https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/leoka-resources.

In the 30 years between 1985 and 2014, the trend rose slightly higher. During this period 69.7 percent of officers killed with firearms in the line of duty were murdered within 0 to 10 feet of perpetrators. Offenders shot approximately half—50.9 percent—of these officers within a distance of 0 to 5 feet. The statistics demonstrate that the number of officers who die decreases as the distance between the officer and offender incrementally increases to 50 feet or more.4

While the statistics include close-proximity murders using firearms, offenders may employ other weapons at close range. Although the distances between the officers and offenders are not published for these weapons, their use inherently requires close proximity. Of the 1,880 total victim officers, the 1985 to 2014 statistics indicate that in addition to the 1,665 officers killed with firearms, offenders murdered 19 with knives or other cutting instruments, 12 with personal weapons (e.g., hands, fists, feet), and 10 with blunt objects. Concerning additional incidents, 13 involved bombs, 83 employed vehicles, and 78 included other types of weapons.5

Interpretation

These statistics support what many law enforcement trainers and supervisors may teach. Maintaining a greater distance between the officer and offender proves critical in preventing assaults or felonious deaths of law enforcement personnel.

Frequently, a uniformed officer may not know the background of the subject when conducting a traffic stop, contacting a suspicious person, or handling a call for service. To enhance safety, the officer must remain professional, vigilant, and cautious during all law enforcement interactions. When initiating a contact, pat-down search, foot pursuit, or arrest, the officer should remain mindful of potential risks.

To minimize those dangers, law enforcement officers should attempt to maintain a greater distance between themselves and a suspect when necessary, take cover if possible, and request backup personnel before confronting an armed offender. As the distance between officer and offender closes, the time for law enforcement personnel to observe, evaluate, and effectively respond to threatening behavior decreases.

Conclusion

The FBI’s annual publication Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted provides details concerning this and other topics, including information about officers killed feloniously or accidentally or assaulted while performing their duties.6 Local, state, tribal, and federal agencies throughout the United States contribute the information to the LEOKA program. These data provide insight into national trends and various factors affecting officer safety. The publication includes 137 tables of information that trainers, supervisors, and managers can use to educate law enforcement personnel and create awareness that can enhance officer safety and prevent injuries or deaths.

Mr. Young can be reached at Marcus.Young@ic.fbi.gov for inquiries and to obtain information on free law enforcement training.

Endnotes

1 Marcus Young, “Good vs. Evil: A Story of Officer Survival,” Law Officer, October 2006, 38-47.

2 Ibid.

3 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted, 2014, accessed June 23, 2016, https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/leoka/2014/officers-feloniously-killed.

4 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program, https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/leoka-resources.

5 Ibid.

6 Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted, 2014.