Perspective

The Phenomena of Workplace Violence

By George Cartwright, Psy.D.

On September 1, 2010, James J. Lee entered the Discovery Channel’s communications building in Silver Spring, Maryland, strapped with explosive devices. Once inside, he took three hostages and stated that he was protesting the channel because its environmental programming did little to save the planet. He further added that shows, such as “Kate Plus 8” and “19 Kids and Counting,” promoted population growth. Throughout the ordeal he repeatedly said that he did not care about the hostages and was ready to die. After a 4-hour standoff, a police SWAT team shot and killed Lee. Fortunately, no one else was injured.

Incidents of workplace violence are common throughout the United States, but rarely as extreme as the incident at the Discovery Channel. One million violent crimes occur in the workplace annually.1 A report issued in May 1995 revealed that on every workday 16,400 violent threats are made, 723 workers are physically attacked, and 43,800 are harassed.2 The cause of these violent acts can include “outsourcing, downsizing, automation, reduced tax revenues, budgetary shortfalls, and increased demand for public services.”3 According to a workplace violence survey, 61 percent of organizations respond to violent threats and assaults based on the situational circumstances.4

Defining Behaviors

The typical image of workplace violence usually involves disgruntled former employees armed with multiple weapons returning to their place of business to rectify a perceived wrong done to them. The altercation inevitably ends with a perpetrator’s death through suicide or by the police. Every news channel will broadcast the incident, and people interviewed who knew the suspect will comment on what a shock it was because the person did not seem dangerous to them.

Even though homicide is the most publicized form of violence in the workplace, it is not the most common. One agency defines workplace violence as “any physical assault, threatening behavior or verbal abuse occurring in the work setting.”5 Myriad behaviors fall into this category; these include homicide, rape, robbery, aggressive posturing, stalking, threats, rude gestures, and harassment.6 Some may not be interpreted immediately as violence, but many people will witness them in their lifetimes.7

Preventing Incidents

Dr. Cartwright is a criminology instructor at Reedley College in Reedley, California.

Crisis consultants have improved radically in handling two aspects of workplace violence.8 The first involves assessing the likelihood that a person who makes a threat will act on it. The second area is in the response—more specifically, responding in ways that both defuse the threat and protect those most vulnerable.

Several best practices can help prevent violence in the workplace. These include setting additional security in place; notifying law enforcement; seeking a temporary restraining order (TRO) against the person who poses the threat; and, if the person is an employee, referring the individual to an employee assistance program (EAP).9 However, these actions are not foolproof. For example, with regard to added security, authorities must consider the length of time the security will remain in place, the rationale behind eventually discontinuing its use, and the measures established to prevent the person who made the threat from reappearing once the security no longer is present.10

Law enforcement agencies are limited to a certain degree until the threatening person actually commits a crime. Police officers cannot arrest someone for what that person may do in the future. A TRO is only effective if the restrained person honors it. If individuals decide to act irrespective of a court order, the piece of paper will not stop them. Also, EAPs provide only limited information to an organization regarding one of its employees. Additionally, EAP professionals frequently lack necessary expertise in handling workplace violence.

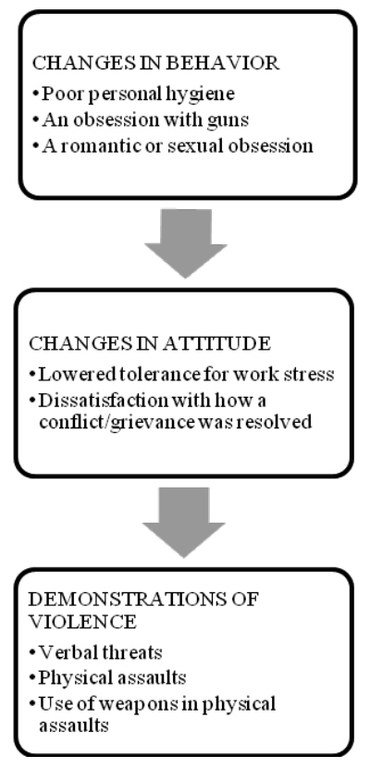

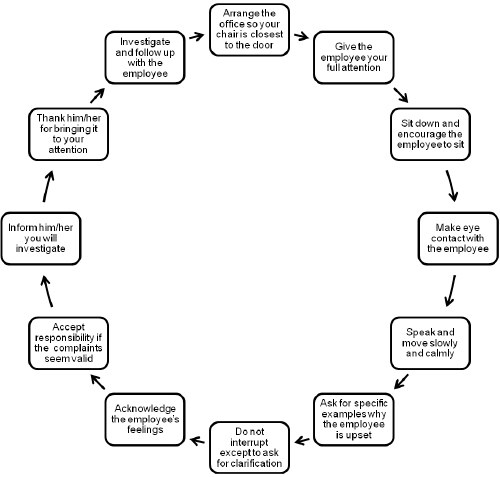

FIGURE 1: Warning Signs

Managers can help prevent workplace violence by indentifying the warning signs that an employee may become violent. As shown in figure 1, three apparent indicators are changes in behavior, shifts in attitude, and demonstrations of violence.11 Other signs may include few friends and little social support, unexplained absences, lack of adequate housing or health care, addictions, and depression.12 Managers recognizing these warning signs can work with the angry employee through a 12-step process, shown in figure 2.13 In addition to being aware of warning signs, it is important to be conscious of triggering events that may lead to acts of violence.14

- Submission of a grievance that was ignored

- Termination of employment (fired or laid off), passed over for promotion, or suspended

- A personal crisis, such as a failed romance

- Escalation of domestic problems

- Disciplinary action, a poor performance review, or criticism from a boss or coworker

- Bank or court action, such as a foreclosure, restraining order, or custody hearing

- Benchmark date, such as an anniversary, birthday, or date of a high-profile bombing

Creating a safer physical environment also is an ideal way to enhance workplace violence prevention.15 This may involve restricting areas accessible to the public; modifying the landscape by increasing visibility around buildings and improving lighting; limiting the amount of cash kept on hand; and installing a security system. More so, training employees in interpersonal communications so they can deal effectively with disgruntled peers also is helpful. A progressive system of discipline for personnel can be established to this end. For instance, in step one, a warning may be issued when an angry outburst occurs; step two may involve asking the person to leave the premises; step three may call for the intervention of security personnel or the police.16

FIGURE 2: How To Deal with Angry Employees

Hiring Right

Workplace violence prevention starts with hiring.17 The process begins with requiring potential employees to thoroughly answer the questions on their job applications. The wording of the application should warn that giving false or misleading information will result in either rejection of the application or termination of employment. An applicant background check also should be conducted, focusing on any criminal history, verification of past employment, and confirmation of the person’s social security number and driver’s license. The investigative and screening efforts made on behalf of the potential employee should be documented, even if all the information received is favorable.18

Employers can be held responsible for the harm their employees cause. Several legal theories may be used to try to impose liability on the employer for the intentional and negligent violent acts of employees, citing negligence in hiring and negligent retention. While a thorough analysis of the liability an employer may face is outside the scope of this article, reference to a few basic steps that can be taken to help minimize the risk of liability, as well as harm to others, should be noted.

In addition to screening out unsuitable applicants with the background check process, employers should focus on adopting effective workplace policies and practices to address unacceptable behavior. One example is a zero-tolerance policy towards violence in the workplace.19 Such a policy should include a preassigned contact person in the event an employee becomes aware of a potentially threatening situation or individual, a nonretaliation statement, and guidelines for managers when they become aware of a policy violation.20

Conclusion

Though organizations may be tempted to turn a blind eye to violence in the workplace, injuries stemming from such incidents potentially can cost them $202 billion per year.21 These costs include property restoration, psychological care for employees, extra security personnel, and organizational image renovation. Ultimately, it is incumbent upon everyone in an organization to take responsibility for their own safety. More so, it is vital that employers create a sense of hypervigilence in their employees by providing formal training in workplace violence prevention.

Endnotes

1 Delaney J. Kirk and Geralyn McClure Franklin, “Violence in the Workplace: Guidance and Training Advice from Business Owners and Managers,” Business and Society Review 108, no. 4 (December 2003): 523.

2 Ibid.

3 Sally Bishop, Bob McCullough, Christina Thompson, and Nakiya Vasi, “Resiliency in the Aftermath of Repetitious Violence in the Workplace,” Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 21, no. 3 (2006): 102; and Jenny M. Hoobler and Jennifer Swanberg, “The Enemy Is Not Us: Unexpected Workplace Violence Trends,” Public Personnel Management 35, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 229.

4 Hire Right, “Survey Reveals How Employers Manage Workplace Violence Incidents,” entry posted May 7, 2012, http://www.hireright.com/blog/2012/05/survey-reveals-how-employers-manage-workplace-violence-incidents/ (accessed February 26, 2013).

5 Kirk and Franklin, “Violence in the Workplace,” 525.

6 Duncan Chappell and Vittorio Di Martino, “Violence at work,” Asian-Pacific Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety 6, no. 1 (1999).

7 Bishop et al., “Resiliency in the Aftermath of Repetitious Violence in the Workplace.”

8 Bruce T. Blythe and Teresa Butler Stivarius, “Defusing Threats of Workplace Violence,” Employment Relations Today 30, no. 4 (Winter 2004).

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid., 64-5.

11 Kirk and Franklin, “Violence in the Workplace.”

12 Lynn Lieber, “Workplace Violence – What Can Employers Do to Prevent It?,” Employment Relations Today 34, no. 3 (Fall 2007).

13 Kirk and Franklin, “Violence in the Workplace.”

14 Lieber, “Workplace Violence.”

15 Hoobler and Swanberg, “The Enemy Is Not Us.”

16 Ibid., 243-44.

17 Lieber, “Workplace Violence”; Kirk and Franklin, “Violence in the Workplace”; and Paul Viollis, Michael J. Roper, and Kara Decker, “Avoiding the Legal Aftermath of Workplace Violence,” Employee Relations Law Journal 31, no. 3 (December 2005).

18 Lieber, “Workplace Violence.”

19 Kirk and Franklin, “Violence in the Workplace”; and Lieber, “Workplace Violence.”

20 Kirk and Franklin, “Violence in the Workplace.”

21 Hoobler and Swanberg, “The Enemy Is Not Us.”