The Concealed Information Test

An Alternative to the Traditional Polygraph

By Blake McConnell and Timothy J. Weber, Ed.D.

The traditional polygraph Comparison Question Test (CQT) detects deceit in response to direct, accusatory questions, such as “Did you stab that man?” However, the Concealed Information Test (CIT), also known as the Guilty Knowledge Test, is a polygraph technique designed to detect a person’s guilty knowledge of a crime.

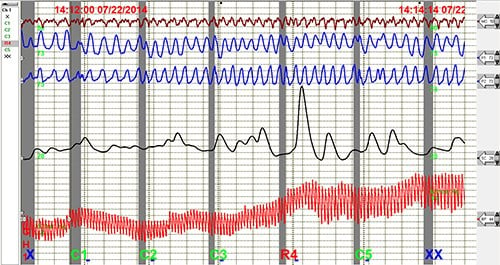

Illustration

A scenario illustrates how the CIT is used to support a homicide investigation. The body of a victim who apparently died of stab wounds is discovered inside a vacant house. Investigators analyze evidence from the crime scene to identify items most likely to be memorable and important to the perpetrator. The following objects are noted: a broken window used to gain entry; a bloody knife, identified as the murder weapon, near the body; a towel used to gag the victim; duct tape used to bind the victim; and a sleeping bag that covered the body. The investigating agency keeps this holdback information confidential.

An identified suspect denies any knowledge of the crime. A CIT is constructed to determine if this individual recognizes elements from the crime scene that only the perpetrator would know. The investigator asks direct questions during the CIT.

- Concerning the weapon used, was it a rope?

- Was it a baseball bat?

- Was it a handgun?

- Was it a knife?

- Was it a crowbar?

The polygraph examiner embeds the key question about the actual murder weapon—the knife—among several control questions about items not tied to the crime scene.1

Key Questions

During a CIT the examiner instructs the suspect to answer “no” to all questions on the test. The actual perpetrator of the crime usually has physiological reactions to the correct, or key, items that can be discriminated from those pertaining to the decoy or control items. It is unlikely that someone not involved with the crime would consistently have strong reactions to the key items. With the administration of numerous tests, it becomes almost mathematically impossible for an innocent person to react randomly to the majority of key questions.2

Mr. McConnell is a retired FBI special agent and a polygraph examiner for the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s Polygraph Branch.

Dr. Weber is a former federal polygraph instructor.

A numerical evaluation of the test data is conducted, resulting in a percentage of decision accuracy. The number of key items tested significantly impacts this precision; therefore, the CIT should include as many as possible. Conclusive results of a CIT with a large number of key items provide a high level of confidence.

The primary goal of key selection is to identify items that are significant and memorable to the perpetrator but unknown to an innocent examinee. A knife brought to a crime scene and used to stab a victim would be memorable to the perpetrator, while a coffee table broken during an altercation may not be. Items associated directly with the perpetrator’s objective in committing the crime make useful key items, while numbers or colors of items lack saliency.3

A rope used to bind a victim is more memorable to a perpetrator than the color of a victim’s clothing or the number of times that a victim was stabbed. Unexpected interruptions in the criminal’s plan also are significant. A valuable item stolen from the crime scene should be particularly relevant to the perpetrator. Key selection requires experience evaluating crime scenes from a behavioral perspective to ensure that items selected for testing have the highest potential for being memorable and salient to the offender.4

Japanese Polygraph

With over 5,000 administered annually in Japan, the CIT has been the dominant polygraph technique since the 1950s and is used exclusively by the country’s law enforcement personnel for criminal investigations. Japanese polygraph examiners traditionally visit crime scenes and are required to be experts in crime scene analysis. The Japanese consider the process of selecting key items for a CIT as an investigation within itself and, as such, conduct a careful analysis of each crime scene.5 Japanese investigators who are aware of the requirements of the CIT protect more holdback information than their U.S. counterparts.

Advantages

The CIT is particularly useful when a child abduction case turns into a homicide investigation. In such cases investigators frequently use polygraph examinations to narrow suspect pools. Subsequently, the investigation may focus on a suspect who previously was tested with a standard CQT polygraph when the child initially was identified as missing. While the benefit of administering another CQT may be negligible, the CIT allows for an evaluation of the person’s guilt from a narrower, more specific perspective.

Based on polygraph theory, the emotional state of an examinee is less likely to influence the accuracy of the CIT than it would the CQT. The CQT is not recommended for use immediately after interrogation of a suspect; however, there is no reason an interrogation should influence CIT accuracy unless crime scene information was divulged.6 Individuals accused by the media, advocates of the victim, and family members may become sensitized to the relevant questions on a CQT, making the CIT a more viable option.

Polygraph Research

Many researchers have concluded that the CIT is more appropriate for testing psychopathic offenders who demonstrate a lack of emotion associated with the defensive-type responses underlying CQT theory. There may be an increase in orienting response—upon which the CIT is based—associated with psychopathy; therefore, psychopaths may be more suitable for CIT testing than others.7

Research highlighting the CIT’s strong theoretical foundation has caused some researchers to theorize that results of a properly constructed and administered CIT will meet the necessary criteria for the admissibility of scientific evidence in U.S. federal courts.8 According to a recent study, one federal law enforcement agency uses the CIT in only 10 percent of its criminal investigations. This is due to the lack of test keys or loss of potential keys resulting from release to the media or use in previous interviews. These findings generalize to other investigative agencies.9

Many large law enforcement organizations have a behavioral analysis component to assist local police departments in identifying key items during crime scene analysis. For U.S. law enforcement agencies to increase the frequency of use of the CIT, there must be a coordinated effort by investigators and polygraph examiners to facilitate its use in criminal investigations.

Conclusion

The Concealed Information Test detects a person’s guilty knowledge of a crime, unlike the traditional polygraph Comparison Question Test that assesses deception to direct, accusatory questions. Investigators analyze crime scene evidence to identify items most likely to be memorable and important to the offender. Extensive use of the CIT by Japanese investigators is indicative of its effectiveness. It is particularly useful when a second polygraph examination is required, such as in a child abduction leading to a homicide investigation. Research also has indicated that the CIT is more appropriate than the CQT for testing psychopathic offenders. According to polygraph theory, the emotional state of an examinee is more likely to affect the accuracy of a CQT than a CIT. Investigators and polygraph examiners must work closely together to increase use of this valuable tool in the United States.

Mr. McConnell may be contacted at blake@icasllc.com, and Dr. Weber may be reached at Timothy.J.Weber.ctr@nga.mil.

Training in the CIT is available from schools accredited by the American Polygraph Association. Additional information on the CIT may be found at http://www.polygraph.org/section/training/apa-accredited-polygraph-programs.

Endnotes

1 Donald Krapohl, James McCloughan, and Stuart Senter, “How to Use the Concealed Information Test,” Polygraph 38, no.1 (2009): 34-49.

2 Gershon Ben-Shakhar and Eitan Elaad, “The Validity of Psychophysiological Detection of Information with the Guilty Knowledge Test: A Meta-Analytic Review,” Journal of Applied Psychology 88, no.1 (February 2003): 131-151.

3 Makoto Nakayama, “Practical Use of the Concealed Information Test for Criminal Investigation in Japan,” in Handbook of Polygraph Testing, ed. Murray Kleiner (London, UK: Academic Press, 2002): 49-86.

4 Ben-Shakhar and Elaad, “The Validity of Psychophysiological Detection of Information with the Guilty Knowledge Test: A Meta-Analytic Review.”

5 Japanese National Research Institute of Police Science, “The Polygraph Examination in Japan” (unpublished slide presentation, Japan, 2009).

6 Krapohl, McCloughan, and Senter, “How to Use the Concealed Information Test.”

7 Bruno Verschuere, Geert Crombez, Armand De Clercq, and Ernst H.W. Koster, “Autonomic and Behavioral Responding to Concealed Information: Differentiating Orienting and Defensive Responses,” Psychophysiology 41, no. 3 (May 2004): 461-466.

8 Gershon Ben-Shakhar, Maya Bar-Hillel, and Mordechai Kremnitzer, “Trial by Polygraph: Reconsidering the Use of the Guilty Knowledge Technique in Court,” Law and Human Behavior 26, no. 5 (October 2002): 527-541.

9 John Podlesny, “A Paucity of Operable Case Facts Restricts Applicability of the Guilty Knowledge Technique in FBI Criminal Polygraph Examinations,” Forensic Science Communications 5, no. 3 (July 2003).

“The primary goal of key selection is to identify items that are significant and memorable to the perpetrator but unknown to an innocent examinee.”

“The CIT is particularly useful when a child abduction case turns into a homicide investigation.”