“Crisis” or “Hostage” Negotiation? The Distinction Between Two Important Terms

By Jeff Thompson

Crisis negotiation has been described as being one of law enforcement’s most effective tools. As we celebrate the anniversary of the world-renowned Hostage Negotiation Team (HNT) that was created in 1973 by the New York City Police Department (NYPD), it is worth taking a look at the use of the words “crisis” and “hostage.”

The NYPD’s HNT was the first-ever unit created to deal specifically in negotiating with individuals involved in a crisis and possible hostage situation. To this day, they are looked upon as one of the best in the world. Prior to the creation of the HNT, the standard police response to these situations was to tell the person to surrender immediately—if the individual did not comply, police personnel would lay siege in an attempt to resolve the situation.

This method of response contributed to the people involved (including the hostage taker, the hostages and victims, police, and bystanders) being injured and sometimes killed in various incidents. The HNT provided what is common in conflict resolution practices—an alternative method based on communication skills and collaboration.

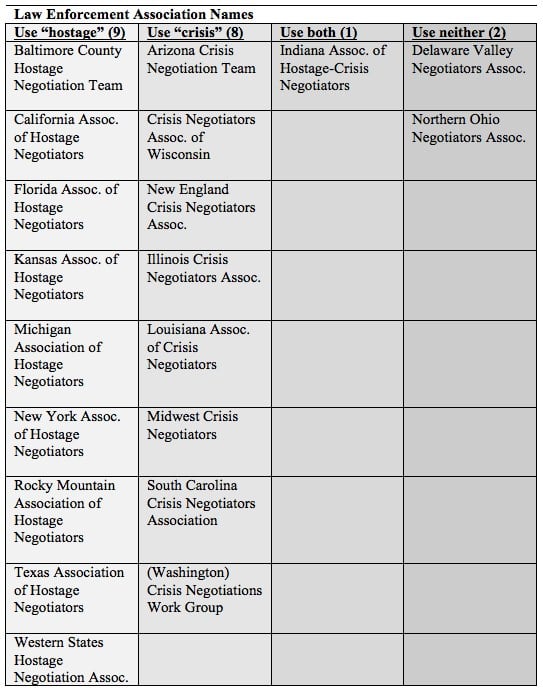

As time has passed since the NYPD’s HNT was created, something noticeable has occurred in the realm of law enforcement hostage negotiation—the emergence of the word “crisis” being used and often replacing the term “hostage.” Reviewing academic literature, one will find the term “crisis negotiation” being commonly accepted while television and other media outlets still refer to “hostage” as the generalized term.1

Detective Thompson is the recipient of the New York Police Department’s Raymond W. Kelly Graduate Scholarship and is currently on academic leave examining hostage and crisis negotiation as a research fellow at Columbia University Law School.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Crisis Negotiation Unit (CNU) is arguably the most well-known negotiation unit due to, among many other reasons, the professional and comprehensive training they provide to their special agents and law enforcement agencies across the country, as well as to foreign police personnel. The FBI’s unit however does not have the word “hostage” in its name.

Are the words “crisis” and “hostage” interchangeable? Is there a difference between the two? If so, which is the correct word? The quick answers are no, yes, and it depends.

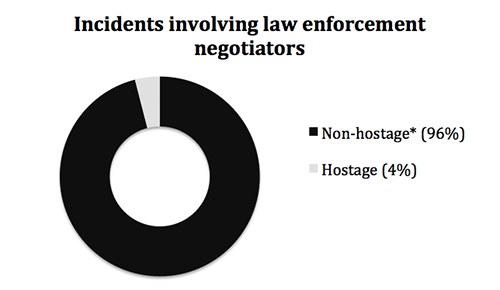

* Non-hostage incidents include barricaded subjects with or without victims, and suicidal subjects. Source: FBI HOBAS. Report generated August 22, 2013.

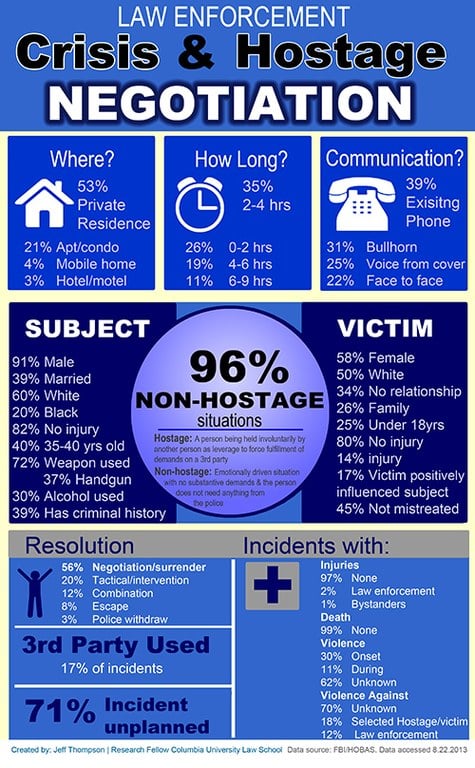

According to the Hostage Barricade Database System (HOBAS)—a database containing information about barricade incidents maintained by the FBI’s CNU—96 percent of incidents requiring the response of law enforcement do not include a hostage being taken. That means only 4 percent of these situations involved a person taking another person or persons hostage. The infographic in Table 1 has additional hostage and crisis negotiator data provided by HOBAS.

A hostage is a person taken involuntarily and being held by the perpetrator with plans to trade them for something else in return. This can include a mode of transportation with plans to escape, money, release of prisoners, or items such as food and drinks.

What is it then when a person is being held against their will yet the situation does not fit the above example? Both situations would be considered a “crisis,” yet in the second situation, the person that is being held involuntarily would not be called a “hostage” but rather a “victim.” Therefore, a hostage situation is one type of crisis to which law enforcement negotiators will respond.

Looking at the statistics, if only 4 percent of incidents involve a hostage situation, what do the rest entail? Included in the remaining 96 percent are emotionally-driven crises where a person is barricaded by themselves or with one or more victims, or is suicidal. In these situations, the person is not making substantive demands or asking for anything from the police because they do not need anything from the police. Rather, they are in crisis, meaning that their normal coping mechanisms for dealing with life’s day-to-day challenges have been overwhelmed. Their emotion level is high while their rational ability is low.

Table 2

While reviewing the names of police associations related to hostage and crisis negotiators, there is not a clear preference with respect to using “crisis” or “hostage” in a given name. Table 2 details this while also showing two cases in which neither is used and one in which both are used.

It is not the suggestion of this author that units or associations should be using the word “crisis” based on the HOBAS statistics—rather, this article has set out to explain the distinction between the two terms. Is this distinction worth considering when deciding which word to use? The choice is yours—at the very least you are informed.

Detective Thompson can be contacted at mediator.jeff@gmail.com.

Endnotes

1 Amy R. Grubb, “Modern day hostage (crisis) negotiation: The evolution of an art form within the policing arena,” Aggressive and Violent Behavior 15, no. 5 (2010): 341-348.