Creating the Preferred Future Today for Law Enforcement Cooperation Tomorrow

A Case Study

By Mike Masterson, Ernst Weyand, and Douglas Hart, M.B.A.

We study the future to forecast future events (the probable future) and circumstances that could occur (the possible) and also to make choices about the events we hope will occur (the preferable).1

Early in his career in the 1970s, the chief of the Boise, Idaho, Police Department, then a young officer in Madison, Wisconsin, had the opportunity to hear an FBI special agent and futurist talk about trends that would impact policing.2 More than two decades later in 2007, those same messages were refined further and shared by several members of the Futures Working Group with law enforcement leaders in the Ada County, Idaho, area.3

The messages received left no doubt that police agencies would have to fundamentally redefine themselves in every aspect of their work to survive and maintain their operational efficacy in an increasingly complex world influenced by accelerating technological and societal developments.4 Beyond those forecasted changes, one of the most relevant insights shared was the importance of networking. A lot of uncertainty exists regarding the best ways to organize for the future, but there exists a growing consensus that the present form of how agencies organize to deliver their services—the pyramidal hierarchical structure—“is increasingly demonstrating its vulnerabilities and ineffectiveness in the Information Age.”5

Mr. Masterson retired as chief of the Boise, Idaho, Police Department.

Special Agent Weyand heads the FBI’s Boise, Idaho, resident agency.

Special Agent and Task Force Coordinator Douglas Hart serves in the FBI’s Boise, Idaho, resident agency.

EMBRACING CHANGE

Only by trying new ideas today will law enforcement find the answers to these perplexing questions about tomorrow. Agencies have to remain committed to creating a more ideal future. And, their personnel have to stay willing to step outside their comfort level and take a risk.

Individuals and organizations are not relegated to passively await the arrival of a predefined future; they have the ability to identify the future they would like to see and to work toward bringing that vision to fruition. We know change is inevitable; rather than being resisted, futurists believe change should be embraced.6

One major obstacle to pursuing these collaborations often is the mind-set of police leaders. Most of them have grown comfortable in leading highly centralized, hierarchical organizational structures, and although agencies work in community-based partnerships (e.g., with neighborhood and business groups), they seldom have collaborated with other law enforcement entities.

Successful crime prevention, deterrence, and investigations require teamwork, but reservations remain about participating in multiagency teams or task forces for a variety of reasons, primarily the perceived loss of control over people and jurisdictions and the possibility of being blamed for problems. Additionally, there are the legendary turf wars that occurred years ago. Certainly, there always exists a fair amount of uncertainty and skepticism in committing to these partnerships based on past hurts, comfort in maintaining the status quo, and the largest obstacle—fear of the unknown. Perhaps, it is for good reason as noted in Policing 2020.

Forecasting possible future police structures and leadership models is an exercise at best. It is likely that police leadership must develop means to adapt and loosen the bureaucratic ropes that bind police agencies under traditional hierarchies. What is left for research is how to implement such networked, flexible organizations without abandoning the key principles of effective policing and losing the ability to hold the police accountable for outcomes and conduct.7

British agencies, guided by the Nine Principles of Sir Robert Peel, have slowly advanced the concept of interagency cooperation.8 Of course, as nearly 200 years have passed since the principles were outlined, contemporary police leaders can improve on the foundation of modern community-policing tenets. In researching better ways to deter crime and disorder, one officer suggested a 10th principle that Sir Peel may have added if he were alive today: “The police should work efficiently with partners in all arenas as appropriate to the problem or issue they are engaged in resolving—be that public, private, or voluntary sectors.”9

SHARING THE SPOTLIGHT

That 10th principle highlights an important topic—working together. The FBI’s Boise, Idaho, resident agency played a key role in bringing numerous law enforcement leaders together to discuss better communication, coordination, and cooperation, which help create safer communities.10

Model for the Future

To this end, the authors present an example of successful collaboration and explain the key characteristics necessary to replicate similar models elsewhere. The formation and continued operation of the Treasure Valley Metro Violent Crime Task Force (TVMVCTF) presents an excellent case study on how to successfully accomplish this challenge.11

In the early 1990s the FBI recognized on a national level that significant changes needed to take place to more effectively combat the increasing levels of violent crime nationwide. The traditional organizational structure, which at that time for the FBI meant addressing these crimes through violent crime major offense squads, could be improved upon, and the proposed solution was to build a network of cooperative relationships via the implementation of FBI-led violent crime task forces. In 1992 the FBI unveiled its Safe Streets Initiative, which created federal, state, and local partnerships that allowed agencies to cross jurisdictional boundaries and combine resources to assist each member organization, thus, maximizing the benefit to public safety.12

This networking initiative has seen resounding success. At the present time over 160 violent crime task forces exist nationwide.13 The effectiveness of these FBI-funded teams rests on the collaborative partnerships between the FBI and the participating state and local agencies that form an integral part of this effort. The networking represented by the participation and cooperation of state and local agencies that provide full-time personnel to work on these multiagency organizations forms one of the key factors in the program’s success.

Relationships between the FBI and its state and local partners have grown, flow of information between agencies has improved, level of trust has strengthened, and all organizations have benefited by the “force-multiplier” effect represented by the task forces. By contributing one full-time employee, each agency essentially gains access to and derives benefits from the work of the entire team, which generally consists of several persons. With these task forces the whole exceeds the sum of the parts.

Necessary Components

There are two fundamental prerequisites for networking—developing relationships and building trust, both essential to forming special groups, like TVMVCTF. Such changes do not happen overnight and will not occur spontaneously. Building trust may start with an honest conversation. Leaders can talk about their organizations and goals and evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, and concerns of forming a task force. Further, they should agree that one agency will take the lead; with it comes the responsibility that everyone will trust the decisions made.

The decision to form a federally funded violent crime task force in Boise was not taken lightly. It involved significant commitment on the part of several different law enforcement agencies. However, recognition of the need for a cooperative and collaborative effort to address an explosion of violent gang crimes in the region fueled the initiative. The traditional efforts of any single agency could not solve the growing problem, and the need became apparent for a flexible, networked organization to appropriately deal with the gang violence that crossed many of the jurisdictional boundaries in the area.

In 2004 Treasure Valley experienced an explosion of gang violence. In August 2004 the city of Caldwell, Idaho, experienced in excess of 100 reported drive-by shootings.14 In 2006 in the neighboring city of Nampa, Idaho, over 240 drive-by shootings occurred that year.15 Clearly something had to be done, and the cities and counties affected by the violence needed to work together to solve this problem. In October 2005 TVMVCTF was formed with nine full-time participating agencies given the mission to address violent crime in the region. In over nine years of its existence, TVMVCTF has proven a successful cooperative effort.

In examining TVMVCTF as a case study in networked, cooperative law enforcement, the authors have identified four suggested components: 1) well-defined mission, 2) the right people, 3) teamwork environment, and 4) shared success. These must be present and agreed upon for a successful cooperative effort.

Well-Defined Mission

From its inception in October 2005 to the present, the mission of TVMVCTF has remained unchanged. It strives to identify and target for prosecution criminal enterprises responsible for drug trafficking; money laundering; illegal immigrant smuggling; and violent crimes, such as murder, aggravated assault, robbery, and violent gang activity. It also focuses on the apprehension of dangerous fugitives when a current or potential federal investigative interest exists. Simply, the task force disrupts and dismantles criminal enterprises, whether large or small.

A consistent focus on a well-defined mission proves essential, especially in an environment where nine different agencies have a participating interest. The potential has existed for nine different task force members to go in various directions in pursuit of what they considered important investigations. Agreeing upon and adhering to a well-defined mission keep the group focused on top priorities and enable the task force to avoid being distracted by efforts not in line with the stated goals and objectives.

TVMVCTF has taken specific measures to ensure that it does not deviate from its focus. First, members meet every week for a mission-specific briefing to review the efforts of the previous week and make plans for the upcoming week. Second, at least twice each year they conduct a “big-picture” review to verify that their investigations fall within the agreed-upon mission. Third, the task force executive council (made up of the participating agency heads) meets annually to review cases and accomplishments.

Strictly adhering to a well-defined mission has resulted in a consistent string of successful, long-term, complex, multi-subject prosecutions of criminal enterprises and the disruption or complete dismantlement of these organizations. The task force enhances the effectiveness of federal, state, and local law enforcement resources through a well-coordinated initiative seeking the most effective avenues to investigate, convict, and incarcerate dangerous offenders. The group’s results over the past 5 years demonstrate success.

| Outcome | July 2008 to Present |

| Felony Indictments (State/Federal) | 294 |

| Felony Convictions (State/Federal) | 244 |

| Felony Convictions (State/Federal) | 110 |

| Firearms Purchased/Seized | 364 |

| Drugs Purchased/Seized | 210 |

| The discrepancy between indictments, convictions, and sentencing reflects the lag time during the adjudication process. | |

Although these numbers are respectable, the most pertinent question is, What do they mean in terms of a positive impact to the community, particularly in light of the belief that these networked task forces maximize the benefit to the public? The region has become safer.

Drive-by shootings in Nampa and Caldwell, Idaho, have dropped by 98.5 percent in the span of six years, from over 240 such incidents in 2006 to 3 in 2012.16 Additionally, graffiti—a common nuisance and a strong indicator of gang activity—is down by over 50 percent.17 Further, a few years ago the task force conducted a case that resulted in the first federal gang racketeering prosecution in the state of Idaho. In that investigation 23 gang members received sentences—totaling more than 136 years in prison—in federal and state courts.18 The chief of police in one of the gang’s former strongholds stated that the number of gang crimes in his city reduced by 50 percent from 2010 to 2012, attributable to this one major case.19

The Right People

Placing the best personnel is the second critical step.20 Not every law enforcement officer is suited to a task force environment or to a networked, flexible organization. The appropriate leadership structure is imperative to the success of a networked organization, and the assigned personnel also are vital. Everyone from top to bottom has to understand that they will participate in an effort that differs from the traditional hierarchy generally existing within a police department or sheriff’s office. The authors identified specific characteristics when seeking an effective task force leader.

- Manages numerous egos and transforms cultures from “me” to “we”

- Proactively reaches out to other agency leaders and stays in touch

- Understands the mission objective and focuses on solving the case

- Listens to feedback from competent investigators and empowers them to do their jobs

- Recognizes the collective work of the task force, but also credits individual investigators for their teamwork and contributions

The special agent in charge of the FBI’s Salt Lake City office designated one supervisory special agent to oversee TVMVCTF. This supervisor, in turn, designated a special agent to serve as the team’s coordinator. Either the task force supervisor or the coordinator oversees day-to-day operational and investigative matters.

A critical part of the partnership is to get expectations in writing. Members of TVMVCTF agree, in writing, to certain conditions of working together that were memorialized in a memorandum of understanding (MOU). For cases assigned to an FBI special agent or in which the agency’s informants are employed, local police departments have agreed to conform to federal standards concerning investigative strategy; policies and procedures; evidence collection, processing, and storage; and electronic surveillance. However, in investigations to be prosecuted in state court where statutory or common law of the state is more restrictive than comparable federal law, investigative methods employed by FBI case agents conform to the requirements of such statutory or common law pending a decision as to venue for prosecution. Law enforcement leaders start the cooperative initiative by living the values they expect, and nothing holds more importance than displaying teamwork in words—as outlined in the MOU—and actions.

An effective task force officer (TFO) has to possess specific characteristics. TFOs must be team players willing to serve in a support role or take the lead on a case. They must remain flexible, able to manage change, capable of operating under stressful conditions, willing to undertake a wide variety of assignments, and ready to sacrifice personal desires for the good of the group. Additionally, they have to function effectively apart from their parent agencies and accept direction from a supervisor from a different organization. All task force members have to get along and work well together daily, but on a personal level more than an organizational level.

Teamwork Environment

All of the necessary steps can be taken to formalize a networked effort, such as an FBI task force, but the creation of such an entity does not in and of itself guarantee or even generate teamwork. A conscious effort by the designated leader, along with “buy in” from the personnel assigned, is essential to creating a teamwork environment.

When a decision was made by the participating agencies to form TVMVCTF and commitments had been made to assign personnel to this organization, the first step taken to build teamwork was to find an off-site location. Having a designated space enabled the leadership and personnel to see one another every day, be in the same space, and remain free from the daily influence of each parent agency. The Bible contains an adage that a person cannot serve two masters—TFOs have to be free from their parent organizations to build a new team, and colocation builds teamwork.21

Second, the members of this new effort created their own logo and patch and purchased identical

body-armor carriers to create uniformity. By these simple steps, the nine became as one. The markings and uniforms of nine different agencies were replaced by those of the new organization, providing an identity with and sense of belonging to this special unit.

Third, and, perhaps, most important, everyone went to work. The members of TVMVCTF quickly learned that their collective efforts were greater than what any one of them could accomplish alone. The resulting major cases and prosecutions were proof positive that the networked organization was effective. TFOs observed the results of their teamwork as one success built upon another. The buy in needed to form the task force was reinforced many times as a result of the cases generated by the group.

Shared Success

Finally, TVMVCTF works because all members share in the successes of the group. Naturally, every police leader wants to take credit for victory, but one of the reasons this team works so well is that everyone willingly shares in the glory. Local task forces too often struggle over credit and control.

Members of the public do not necessarily keep track of which agency announced solving a particular crime. They want to see criminals put in jail and communities protected. The citizens of Treasure Valley care more about safety than which agency receives the most credit. All media releases and statements are mutually agreed upon and jointly handled according to FBI and participating agency guidelines. When major charging decisions are announced, all agency heads gather for the announcement. If the release of arrest information itself does not convey a strong message of public safety, the symbolism of having, for instance, the U.S. Attorney of Idaho joined by nine law enforcement leaders standing on the podium working together certainly does.

Any law enforcement professionals not working in a networked organization, such as a task force, right now likely will be within the next 5 years. The FBI’s Safe Streets and Gang Unit, which administers 163 Violent Gang Safe Streets Task Forces covering every state and Puerto Rico, is staffed by nearly 850 FBI agents and more than 1,300 state and local law enforcement personnel.22 Additionally, 102 Joint Terrorism Task Forces exist nationwide with nearly 4,000 local officers participating in the initiatives.23

In 2013 DEA managed 259 state and local task forces, staffed by over 2,190 DEA special agents and over 2,556 state and local officers. Participating state and local TFOs are deputized to perform the same functions as DEA special agents.24

The U.S. Marshals Service has a long history of providing assistance and expertise to other law enforcement agencies in support of fugitive investigations. Those regional fugitive task forces combine the efforts of federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to locate and apprehend the most dangerous fugitives and assist in high-profile investigations. The success of U.S. Marshals task force initiatives, combined with the outstanding relationships forged with other law enforcement agencies, has led to the formation of permanent regional fugitive task forces, as well as local task forces in response to unique cases that pose an immediate threat to the public. In fiscal year 2012 U.S. Marshals Service-led fugitive task forces—7 regional and 60 local—cleared by arrest 39,400 federal felony warrants and also arrested more than 86,700 state and local fugitives, resulting in over 114,000 nonfederal warrants.25

FACING THE FUTURE

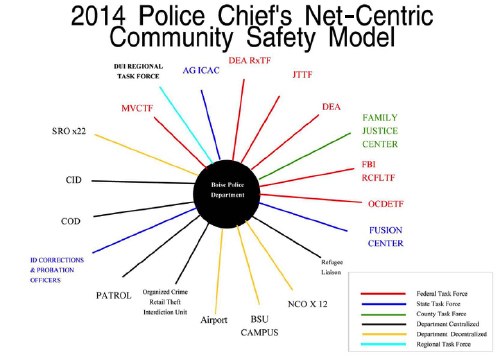

Policing is in a transformational period where agencies are redefining and reengineering police systems that have existed in virtually the same form for nearly 200 years. The terrorist attacks of 2001, followed by the Great Recession, have pushed law enforcement to finding more effective, efficient ways to prevent, deter, and solve crime. It also has caused agencies to reexamine their closely held assumptions on the all-too-familiar pyramidal hierarchy that is slowly being replaced in many organizations with a net-centric model.26

This model is applicable for any leaders overseeing multiagency task forces.

Thirty years of research by a leadership expert revealed that 70 percent of all major change efforts in organizations fail.27 He cited two fundamental elements for successful change—the mechanical and the human. As law enforcement agencies prepare to enter into the new paradigm of leading net-centric policing, they already possess the mechanical, a manager’s mind-set of wanting to manage systems and processes, create policies, and insist on tightly worded official agreements. But, many of them are less familiar with the mind-set of the leader, learning to operate in fast-moving environments that have parameters, but without the structure and operating comfort of the past.

It is a philosophy that is fully compatible with and capitalizes upon the tools and dynamics of the Information Age. The old models concern themselves with procedure, policy, order, and control. Their philosophy is one of process, command, and strict accountability. The net-centric philosophy sets aside those concerns and concentrates on the product, on achieving success, increasing individual productivity, and maximizing the distribution of information to solve real problems. The goal is achieving effective and appropriate solutions quickly in a rapidly changing environment. The net-centric model requires a completely new culture of control, a new structure, new operational methodologies, and the emerging technological tools to facilitate them. It is a philosophy that embraces Information Age technology to maximize human productivity and effectively and efficiently solve human problems.28

CONCLUSION

As law enforcement moves forward, agencies seemingly will become involved in a task force or similar networked effort. The challenge for police leaders will be to remain willing and able to both lead and manage, trust themselves and others, and allow their personnel to participate in networked organizations.

Hopefully the lessons learned and shared in the Boise example will convince law enforcement leaders of the synergy and benefits of fostering regional collaboration, forming multiagency taskforces, or simply partnering with a neighboring agency for the common goal of creating safer communities. The mission of law enforcement agencies worldwide will continue to be to serve, protect, and lead, but within that realm exists the responsibility for police leaders to seek out the most effective and successful methodologies to employ in fulfilling that trust. If carried out correctly, networked organizations, such as the Treasure Valley Metro Violent Crime Task Force, represent one of the best practices available as law enforcement agencies seek through their efforts to maximize the benefit they provide to their communities.

For additional information Mr. Masterson can be contacted at ou76mike@gmail.com, Special Agent Weyand at Ernst.Weyand@ic.fbi.gov, and Special Agent Hart at Douglas.Hart@ic.fbi.gov.

Endnotes

1 Joseph A. Schafer, “Thinking About the Future of Policing,” in Policing 2020: Exploring the Future of Crime, Communities, and Policing, ed. Joseph A. Schafer (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2007), 15, http://futuresworkinggroup.cos.ucf.edu/publications/Policing2020.pdf (accessed December 23, 2014).

2 Dr. William Tafoya, retired FBI special agent.

3 The Futures Working Group is a collaboration between the FBI and the Society of Police Futurists International. Its purpose is to develop and encourage others to develop forecasts and strategies to ethically maximize the effectiveness of local, state, federal, and international law enforcement bodies as they strive to maintain peace and security in the 21st century.

4 Richard Myers, “From Pyramids to Network: Police Structure and Leadership in 2020,” in Policing 2020: Exploring the Future of Crime, Communities, and Policing, 487-517.

5 Ibid., 487-488. See Dana Griffin, “A Hierarchical Organizational Structure,” Houston Chronicle, under “Small Business,” http://smallbusiness.chron.com/hierarchical-organizational-structure-3799.html (accessed December 30, 2014).

6 Myers, “From Pyramids to Network.”

7 Ibid., 517.

8 “Sir Robert Peel’s Nine Principles of Policing,” New York Times, April 15, 2014, under “N.Y./Region,” http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/16/nyregion/sir-robert-peels-nine-principles-of-policing.html?_r=0 (accessed December 30, 2014).

9 Edward Boyd, Policing 2020: What Kind of Police Service Do We Want in 2020? ed. David Skelton (London, UK: Policy Exchange, 2012), http://www.policyexchange.org.uk/images/publications/policing%202020.pdf (accessed December 23, 2014).

10 The FBI has 56 field offices in major cities across the United States, as well as approximately 380 resident agencies. The Boise, Idaho, resident agency operates out of the Salt Lake City, Utah, field office. See U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Quick Facts,” http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/quick-facts (accessed December 23, 2014).

11 Treasure Valley, Idaho, has a population of over 600,000. It consists of two cities, including Boise, and five counties. Boise Valley Economic Partnership, “Demographics of the Boise Valley,” http://www.bvep.org/facts/demographics.aspx (accessed December 23, 2014).

12 Grant D. Ashley, “Testimony” (presented to the Senate Judiciary Committee, Washington, DC, September 17, 2003), http://www.fbi.gov/news/testimony/the-safe-streets-violent-crimes-initiative (accessed December 29, 2014).

13 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Violent Gang Task Forces,” http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/vc_majorthefts/gangs/violent-gangs-task-forces (accessed December 23, 2014).

14 Records from the Caldwell, Idaho, Police Department.

15 Records from the Nampa, Idaho, Police Department.

16 Records from the Nampa and Caldwell, Idaho, Police Departments.

17 Chief Craig Kingsbury, Nampa, Idaho, Police Department.

18 U.S. Attorney’s Office, District of Idaho, “U.S. Attorney Olson Announces Sentencing of Final Two Defendants in Brown Magic Clica (BMC) Gang Racketeering Cases,” http://www.fbi.gov/saltlakecity/press-releases/2013/u.s.-attorney-olson-announces-sentencing-of-final-two-defendants-in-brown-magic-clica-bmc-gang-racketeering-cases (accessed January 13, 2015).

19 Chief Chris Allgood, Caldwell, Idaho, Police Department.

20 James C. Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don't (New York, NY: Harper Business, 2001).

21 Matthew 6:24.

22 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Violent Gang Task Forces.”

23 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Protecting America from Terrorist Attack: Our Joint Terrorism Task Forces,” http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/terrorism/terrorism_jttfs (accessed December 29, 2014).

24 U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, “State & Local Task Forces,” http://www.justice.gov/dea/ops/taskforces.shtml (accessed December 23, 2014).

25 U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Marshals Service, “Fugitive Task Forces,” http://www.usmarshals.gov/investigations/taskfrcs/tskforcs.htm; and U.S. Marshal Brian Underwood, interview by authors.

26 See Thomas J. Cowper, “Network Centric Policing: Alternative or Augmentation to the Neighborhood-Driven Policing (NDP) Model?” in Neighborhood-Driven Policing: Proceedings of the Futures Working Group, vol. 1, eds Carl J. Jensen and Bernard H. Levin (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2005), 21-28, Futures Working Group, http://futuresworkinggroup.cos.ucf.edu/docs/Volume%201/Vol1-NDP-FWG.pdf (accessed December 30, 2014).

27 Kotter International, “The 8-Step Process for Leading Change,” http://www.kotterinternational.com/our-principles/changesteps (accessed December 23, 2014).

28 Cowper, “Network Centric Policing.”