Emergency Medical Response in Active-Threat Situations

Training Standards for Law Enforcement

By John M. Landry, Ph.D.; Sara J. Aberle, M.D.; Andrew J. Dennis, D.O., D.M.E.; and Matthew D. Sztajnkrycer, M.D., Ph.D.

In an active-threat situation, emergency medical services (EMS) personnel may be unable to access the scene. This could require law enforcement officers to render care without EMS assistance to themselves, injured colleagues, or victims. A care gap of this type occurred in two recent high-profile active-shooter incidents.1

To develop law enforcement medical training standards based on identified gaps and needs, it is critical to understand current training levels. Unfortunately, little is known about law enforcement medical training and response in the United States.2 The authors conducted a study that described levels of medical instruction provided to officers and evaluated the impact of specific training on selected medical decision-making skills. For the study they distributed an anonymous Internet-based survey through a law enforcement newsletter. In addition to demographic and training questions, they administered scenario-based survey questions (table 1) developed by a panel of experts.

Dr. Landry, a retired lieutenant from the State of Florida Department of Financial Services, Division of Insurance Fraud, in Tallahassee, is an instructor in the Criminal Justice Program at South Florida State College in Avon Park, Florida.

Dr. Aberle is chief resident of the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Dr. Dennis is chief of the Division of Prehospital and Emergency Trauma Services, Department of Trauma and Burn, at the John H. Stroger, Jr., Hospital of Cook County; medical director of the Cook County Sheriff’s Department, Emergency Services Bureau; and an associate professor at RUSH Medical College in Chicago, Illinois.

Current Requirements

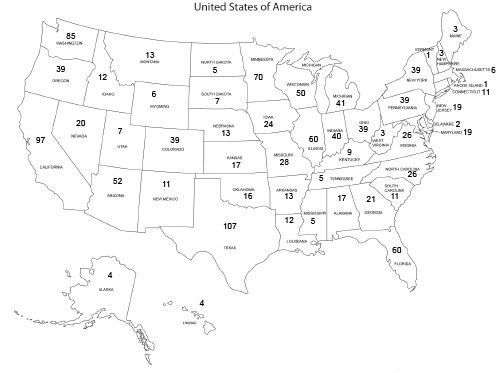

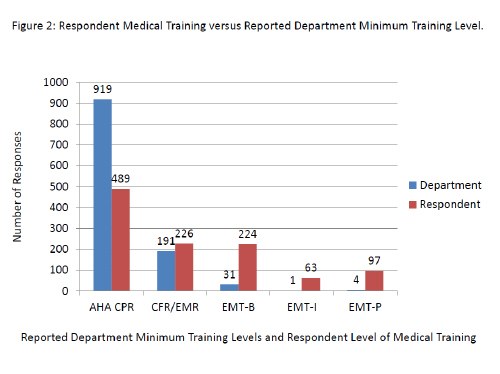

A total of 1,317 law enforcement personnel from across the country (figure 1) completed the survey. Nine hundred nineteen respondents (80.2 percent) reported that their respective agency’s minimum medical training requirement was American Red Cross Basic First Aid/CPR or equivalent (figure 2). These results indicated that the majority of officers had only basic instruction, which may be insufficient for managing medical emergencies encountered while on duty.

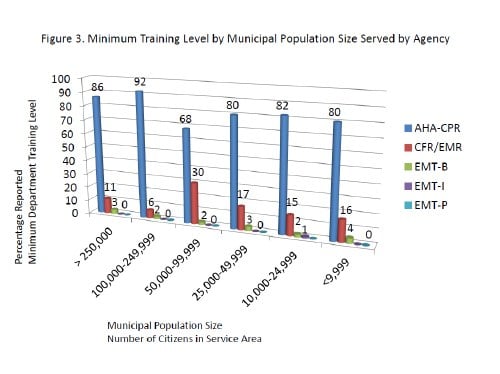

Agencies serving populations with less than 100,000 people were more likely to be trained to the first-responder level or higher than agencies serving populations of greater than 100,000. This seems paradoxical because larger agencies presumably would have more training and greater financial resources to permit higher levels of instruction. The results may reflect the potential for agencies in larger municipalities to serve alongside robust fire and EMS systems with short response and transport times and advanced skill capabilities. Organizations within smaller communities may have fewer available fire and EMS assets (such as volunteer services) and potentially prolonged response and transport times, resulting in a greater need for medical training for police officers. Agencies located in communities with 50,000 to 99,000 citizens reported the highest percentage of minimal training requirements—certified first-responder (CFR)/emergency-medical responder (EMR) level or higher—possibly reflecting a cost-benefit advantage compared with agencies with much smaller or larger populations.

Dr. Sztajnkrycer is an associate professor and chair of Emergency Preparedness in the Division of Emergency Medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and serves as medical director for the Rochester Police Department and Olmsted County Emergency Response Unit in Rochester.

Note: Not all 1,317 respondents provided geographical information.

Key:

AHA CPR: American Heart Association Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation

CFR/EMR: Certified First Responder/Emergency Medical Response

EMT-B: Emergency Medical Technician-Basic

EMT-I: Emergency Medical Technician-Intermediate

EMT-P: Emergency Medical Technician-Paramedic

Key:

AHA CPR: American Heart Association Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation

CFR/EMR: Certified First Responder/Emergency Medical Response

EMT-B: Emergency Medical Technician-Basic

EMT-I: Emergency Medical Technician-Intermediate

EMT-P: Emergency Medical Technician-Paramedic

Victim Statistics

Law enforcement inherently is a dangerous profession. In the past decade an average of 54 officers were killed on duty each year—in 2012 there were 48 victims.3 In a previous study, 41 percent of officers surveyed reported that they had responded to the scene of a seriously injured colleague, and 70 percent of those officers stated that they arrived prior to emergency medical services.4

Agencies increasingly have expressed interest in training officers to provide medical care during active-threat events. Faced with the shooting of 11 officers in a 2-year period, including 2 line-of-duty deaths, the city of Memphis, Tennessee, trained 4 officers to the emergency-medical technician (EMT) basic level.5 The authors’ analyses indicated, however, that higher levels of conventional medical training were not associated consistently with improved scores on tactical medical case-based scenarios.

Training

In the absence of law enforcement-specific medical training, many agencies have turned to their military counterparts and their Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) curriculum.6 This training emphasizes bleeding control based on data showing that the leading cause of preventable death in combat is extremity hemorrhage.7 Recently, a national law enforcement organization recommended that all officers receive training in these skills.8

In the authors’ study, 54 percent of respondents indicated that they received additional departmental training in pressure dressings to control bleeding, while 49 percent reported training in tourniquet use, and 32 percent expressed that they had received instruction in advanced specialty hemostatic agents. Five hundred fifty-five respondents (42.4 percent) reported specific training in TCCC.

Due to the limitations of the study, the nature and quality of such training is unclear. Hemorrhage control ideally would be taught using reality-based training integrated into use-of-force scenarios, as opposed to instructive lectures. Even highly trained personnel underestimate the amount of force required to control hemorrhaging using a tourniquet, emphasizing the need for instruction under realistic conditions.9

During active-threat scenarios, there was no consistent relationship found between the respondent level of civilian medical training and the correct approach to bleeding management. However, the scenario-based questions had limited real-world applicability, and the number of scenarios evaluated was small. In contrast, in 3 out of 4 case-based scenarios, individuals who reported receiving military-style TCCC training were more likely to select the correct responses than those who had not received this training. This suggests that TCCC training is at least equivalent to conventional medical instruction at the CFR/EMR level or higher for evaluating this element of tactical medical decision-making.

TCCC curriculum was developed for combatants in a military environment and has not been validated for use in a civilian population. Data indicates that law enforcement injury patterns differ significantly from the military experience, thus, potentially limiting the real-world use of TCCC skills for law enforcement officers.10 However, the fundamental priorities and tactical concepts of TCCC for providing care under fire are equally important to law enforcement. A civilian counterpart, the Committee on Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (CoTECC), currently is developing guidelines based on the military tactical medicine experience.11

Study Limitations

The authors acknowledge that their study has limitations, including those inherent in any survey-based research. Due to these confines, this survey should not be used to derive specific training requirements for particular injury patterns or survival outcomes. While minimum departmental levels were determined, there were no questions specifically addressing why each agency chose a particular minimum training level. This study primarily focused on assessing skill sets as they relate to trauma care under fire. Therefore, agencies cannot draw suppositions relative to outcomes and abilities to respond to medical emergencies.

| Table 1: Scenario-Based Questions |

| Question 1: You and a partner respond to a domestic violence complaint. As your partner knocks on the door, you hear gunfire from inside the residence. A round comes through the door, striking your partner in the mid-thigh. Your partner falls to the ground. You see pulsatile blood pumping from the wound and realize your partner has been hit in the femoral artery. A large amount of blood is starting to pool around your partner. After calling for assistance and assisting your partner to cover, which of the following actions would be most appropriate in the definitive management of the bleeding? |

|

| Question 2: You respond to an armed-robbery-in-progress call at a local bank. As you approach the front of the bank, a suspect emerges, dressed in black fatigues, a balaclava, and armed with an assault rifle. The person sprints across the parking lot, firing a volley of fully automatic fire. A round strikes you in the left upper arm as you seek cover. Your arm instantly feels numb, and as you examine the wound, you notice brisk, nonpulsatile bleeding. After applying pressure to the wound as you move to a location of cover, which of the following would be the most appropriate next action in the definitive management of the bleeding? |

|

| Question 3: You are assisting in the arrest of a suspected drug dealer during a buy-bust operation. As your partner attempts to cuff the suspect, he spins and slashes your partner's right hand with a razor. You see a modest amount of bleeding. The suspect is taken down, and your partner is calling for help. Which of the following options would be most appropriate for the initial and definitive management of the bleeding? |

|

| Question 4: You respond to the scene of an IED detonation. No secondary device is present. One victim sustained an amputation of the right leg just above the knee. Despite placement of a commercially produced one-handed tourniquet, the victim continues to bleed briskly from the leg. Which of the following would be the next most appropriate step in the definitive management of the bleeding? |

|

| Best responses: 1. B.; 2. C.; 3. C.; 4. B. |

Conclusion

The current minimum medical training for law enforcement officers appears less than optimal for meeting the initial needs of the sick or injured during an active-threat occurrence. Advanced medical instruction may enhance officers’ ability to serve their communities as first responders. However, this may not provide an advantage over more specific training, such as TCCC, if the objective is to improve initial medical response during an active threat. These findings highlight the need for the development of specific law enforcement-focused tactical medical training including rescue-related treatment. Ideally, analogous to use-of-force training, agencies would annually review such programs for ongoing effectiveness and opportunities for improvement.

For additional information Dr. Landry may be contacted at johnmlandryphd@gmail.com, Dr. Aberle may be contacted at aberle.sara@mayo.edu, Dr. Dennis may be contacted at adennis@cookcountytrauma.org, and Dr. Sztajnkrycer may be contacted at sztajnkrycer.matthew@mayo.edu.

Endnotes

1 Mike Baker, “Colorado Shooting: Police Pleaded for Ambulances on Night of Aurora Movie Theater Massacre,” Huffington Post, July 27, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/27/colo-shooting-police-plea_n_1709407.html (accessed November 13, 2014); and Jason Kandel, “TSA Officer Bled for 33 Minutes in LAX Shooting,” NBC Los Angeles, November 15, 2013, http://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/TSA-Officer-Bled-For-33-Minutes-In-LAX-Shooting-232062361.html (accessed November 13, 2014).

2 Hector M. Alonso-Serra, Theodore R. Delbridge, Thomas E. Auble, Vincent N. Mosesso, and Eric A. Davis, “Law Enforcement Agencies and Out-of-Hospital Emergency Care,” Annals of Emergency Medicine 29, no. 4 (April 1997): 497-503, http://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(97)70223-3/abstract (accessed November 19, 2014); and Matthew D. Sztajnkrycer, David W. Callaway, and Amado A. Baez, “Police Officer Response to the Injured Officer: A Survey-Based Analysis of Medical Care Decisions,” Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 22, no. 4 (August 2007): 335-341, http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid= 8557530&fulltextType=AC&fileId=S1049023X00004982 (accessed November 19, 2014).

3 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Information Services Division (CJIS), Uniform Crime Reports, “Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted 2012,” http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/leoka/2012 (accessed November 13, 2014).

4 Sztajnkrycer, Callaway, and Baez, “Police Officer Response to the Injured Officer.”

5 Timberly Moore, “Police Attain EMT Status,” Commercial Appeal (Memphis), April 15, 2013, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-34524720.html (accessed November 13, 2014).

6 Frank K. Butler and Richard Carmona, “Tactical Combat Casualty Care: From the Battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq to the Streets of America,” The Tactical Edge 27, no. 4 (2012): 86-91; and Fabrice Czarnecki, Glenn A. Bollard, David Q. McArdle, John Meade, Peter A. Pappas, Brian L. Springer, and Matthew D. Sztajnkrycer, “Emergency Trauma Care,” International Association of Chiefs of Police Training Keys 40, no. 667 (2012), http://www.theiacp.org/portals/0/pdfs/TrKeyInfoPacket.pdf (accessed November 19, 2014) .

7 Russ S. Kotwal, Harold R. Montgomery, Bari M. Kotwal, Howard R. Champion, Frank K. Butler, Jr., Robert L. Mabry, Jeffrey S. Cain, Lorne H. Blackbourne, Kathy K. Mechler, and John B. Holcomb, “Eliminating Preventable Death on the Battlefield,” Archives of Surgery 146, no. 12 (December 2011): 1350-1358, http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1107258 (accessed November 19, 2014); Ronald F. Bellamy, “The Causes of Death in Conventional Land Warfare: Implications for Combat Casualty Care Research,” Military Medicine 149, no. 2 (March 1984): 55–62; and Frank K. Butler, Jr., John B. Holcomb, Stephen D. Giebner, Norman E. McSwain, and James Bagian, “Tactical Combat Casualty Care 2007: Evolving Concepts and Battlefield Experience,” Military Medicine 172, no. 11, S11 (November 2007): 1-19, http://valorproject.org/uploads/butler_military_medicine_tccc_2007.pdf (accessed November 19, 2014).

8 National Tactical Officers Association, “NTOA Calls for Increased Emergency Medical Training for Cops,” PoliceOne.com (October 8, 2013), http://www.policeone.com/mass-emergency-response/articles/6504699-NTOA-calls-for-increased-emergency-medical-training-for-cops/?source=newsletter&nlid=6504748 (accessed December 4, 2014).

9 David R. King, Gwendolyn M. van der Wilden, John F. Kragh, Jr., and Lorne H. Blackbourne, “Forward Assessment of 79 Prehospital Battlefield Tourniquets Used in the Current War,” Journal of Special Operations Medicine 12, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 33-38, https://www.jsomonline.org/Articles.php?20124#2012433 (accessed December 4, 2014).

10 Matthew D. Sztajnkrycer, “Tactical Medical Skill Requirements for Law Enforcement Officers: A 10-Year Analysis of Line-of-Duty Deaths,” Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 25, no. 4 (September 2010): 346-351, http://www.pubfacts.com/detail/20845323/Tactical-medical-skill-requirements-for-law-enforcement-officers:-a-10-year-analysis-of-line-of-duty (accessed January 20, 2015).

11 David W. Callaway, E. Reed Smith, Jeffrey S. Cain, Geoff Shapiro, W. Thomas Burnett, Sean D. McKay, and Robert L. Mabry, “Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC): Guidelines for the Provision of Prehospital Trauma Care in High Threat Environments,” Journal of Special Operations Medicine 11, no. 3 (Summer/Fall 2011): 104-122, http://www.nfpa.org/~/media/Files/Research/Resource%20links/First%20responders/Urban%20Fire%20 Forum/ UFF%20TECC.pdf (accessed December 4, 2014).