The Evolution of Terrorism Since 9/11

By Lauren B. O’Brien, M.S.F.S.

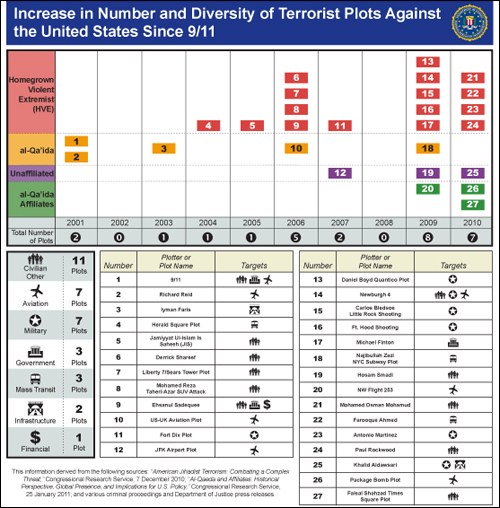

Approximately 10 years after the 9/11 attacks, the United States faces a more diverse, yet no less formidable, terrorist threat than that of 2001. In this increasingly complex and dynamic threat environment, not only does Pakistan-based al Qaeda possess the ability to project itself across the globe to stage attacks against the West but so do groups based in Yemen, Somalia, and Iraq. In many ways, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) poses as serious a threat to the nation as core al Qaeda, with two attempted attacks against the U.S. homeland in the past two years.

In this ever-changing threat environment, America constantly must evolve to keep pace with this adaptive enemy. The United States has had significant successes in combating the terrorism threat, most visibly with the May 2, 2011, death of al Qaeda leader Usama Bin Ladin. Further, the lives saved by U.S. counterterrorism efforts—the arrest of a homegrown violent extremist (HVE) who attempted to attack a Christmas tree-lighting ceremony in Portland or the disruption of three al Qaeda-trained operatives in the United States before they could attack the New York City transit system—stand as equally meaningful victories.

Discussing the current threat environment requires an understanding of how terrorism trends have evolved. These trends remain relevant today in the decade since 9/11.

Terrorism in the Wake of 9/11

Evolving Threat from Al Qaeda

In 2001, what emerged with clarity out of the ashes of the Twin Towers was that no greater threat to the homeland existed from a nonstate actor than that posed by core al Qaeda in Pakistan. Ten years later, the group still demonstrates the intent and capability to attack the United States. Although al Qaeda’s last successful Western attack was in the United Kingdom in 2005, a steady stream of the group’s operatives have been detected and disrupted over the past 10 years in the United States, Norway, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Pakistan.

Counterterrorism efforts against al Qaeda in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) that began with Operation Enduring Freedom in October 2001 have degraded al Qaeda’s abilities, resulting in the loss of key leaders and trainers and making it more difficult for al Qaeda to train operatives, communicate, and transfer funds. In response to these setbacks, the group has refined its modus operandi and developed practices that have allowed it to persevere in a post-9/11 environment.

Seized by the success of 9/11, al Qaeda has maintained its intent to conduct “spectacular” high-casualty attacks against the United States and its Western allies. A review of disrupted al Qaeda plots since 9/11 reveals that the group has continued to focus on high-profile political, economic, symbolic, and infrastructure targets, with a particular fixation on aviation. Al Qaeda also has pursued its interest in staging simultaneous attacks—a theme it has followed from the 1995 Bojinka plot to attack planes over the Pacific, to 9/11, and to the 2006 plan to attack multiple flights from the United Kingdom to the United States. Such sophisticated plots require multiple operatives and longer planning cycles than a simply constructed, less-spectacular plan. In recent years, al Qaeda has evolved and expanded its interests to include small-scale attacks in addition to its pursuit of the spectacular, with the aim of staging a successful attack regardless of size.

Al Qaeda’s preference for acquiring its attack capabilities from locally available resources has held relatively constant. With the exception of “shoe bomber” Richard Reid in 2001, for its Western plots, al Qaeda has relied on well-trained operatives to construct an explosive device after being deployed, using locally available materials. For example, in the July 7, 2005 attacks in London, bombers spent weeks in their ground-floor flat in Leeds constructing explosive devices from readily available commercial ingredients.

Over the past decade, al Qaeda has developed the practice of using operatives with legal access to the United States and other Western nations to target their countries of origin; for example, al Qaeda deployed American legal permanent resident Najibullah Zazi to attack the New York City subway system in 2009 and U.K. citizen Mohammad Sidique Khan to carry out the July 2005 attacks in London. The three individuals convicted of the most serious charges in the 2006 U.S.-U.K. aviation plot, as well as most of their coconspirators, consisted of British citizens of Pakistani descent. Using operatives who not only possess legal travel documents but also language skills and Western cultural understanding can help them to evade security and operate undetected.

Despite setbacks to its training program due to the loss of key leaders and an increasingly difficult operating environment, al Qaeda has continued to recruit and train potential operatives. Identifying American al Qaeda recruits who may travel from the United States to Pakistan to receive training, much like Najibullah Zazi, is one of the FBI’s highest counterterrorism priorities. Yet, U.S. authorities also must remain concerned about European trainees. Because of their visa-free access to the United States through the Visa Waiver Program, al Qaeda could deploy European operatives to the United States for homeland attacks or use Europe as a launching pad for attacks against America, as it did in the disrupted U.S.-U.K. aviation plot.

“These various terrorism trends have resulted in a threat environment more complex and diverse than ever before.”

New York City subway system

Russell Square, London

Birth of the Global Jihadist Movement

Following 9/11, the United States faced a threat from al Qaeda not only as an organization but also as an ideology. A new global jihadist movement composed of al Qaeda-affiliated and -inspired groups and individuals began to unfold. Although these groups threatened U.S. interests overseas, they did not rival al Qaeda in the threat they posed to the homeland. However, over time, the spread of this decentralized, diffuse movement has increased the threats to U.S. interests at home and abroad.

In the early 2000s, a number of al Qaeda affiliates and regional terrorist groups emerged, and, although they took on the name of al Qaeda and adopted its ideology, they largely adhered to a local agenda, focusing on regional issues and attacking local targets. At the time of the 2007 National Intelligence Estimate publication, al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) was the only al Qaeda affiliate known to have expressed a desire to strike the homeland. Within Iraq, AQI inflicted thousands of casualties on coalition forces and Iraqi civilians. Beyond the country’s borders, AQI fanned the flames of the global jihadist movement and claimed credit for the June 2007 failed vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) attack on Glasgow Airport in Scotland.

In addition to al Qaeda-affiliated groups, the United States also saw the emergence of a generation of unaffiliated individuals inspired by al Qaeda’s ideology but lacking ties to any foreign terrorist organization. These HVEs have developed into one prong of a multifaceted homeland threat. Although many have lacked the capability to match their intent, others took steps to move from violent rhetoric into action.

Some of these al Qaeda-inspired Americans sought to travel to Pakistan, Afghanistan, or other fronts in the global jihad to gain fighting experience or participate in terrorist training. The Virginia Jihad Network—a group of individuals disrupted in 2001 after acquiring training from Pakistani militant group Lashkar-e-Tayyiba in preparation for jihad against American forces in Afghanistan—was one of the first cases to shed light on this trend.

Since 9/11, American HVEs have traveled to Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen for terrorist training and ultimately joined terrorist groups in those countries. For example, Bryant Neal Vinas, a convert to Islam who was raised in Long Island, New York, traveled to Pakistan in September 2007 and managed to join al Qaeda. There, he participated in attacks against coalition forces and provided al Qaeda with insight for homeland attacks, including one potentially targeting the Long Island Rail Road. The primary concern with Vinas and other American trainees is that al Qaeda or its affiliated groups will leverage them for homeland attacks, as they sought to do with Najibullah Zazi before his plot to attack the New York City transit system was disrupted in 2009.

Other HVEs have attempted to stage attacks inside the United States. In the years since 9/11, the FBI and its law enforcement partners have disrupted over a dozen plots perpetrated by HVEs. Although many were unsophisticated, small-scale plots, like Derrick Sharreef’s 2006 plot to attack a shopping mall food court with a hand grenade, others were more ambitious, like the one involving five individuals who conspired in 2007 to attack soldiers stationed at the Fort Dix Army Base in New Jersey. Based on the number of disruptions and indictments, the number of HVEs undertaking terrorist actions in the United States appears to have increased over the past 10 years.

Unfortunately, the appeal of the al Qaeda narrative has not diminished, and issues, like the war in Iraq, the United States and NATO presence in Afghanistan, and Guantanamo, serve to inflame and, perhaps, radicalize those sympathetic to al Qaeda’s ideology. The decentralized global jihadist movement has become a many-headed hydra, with al Qaeda-affiliated and -inspired groups playing an increasingly prominent role in the overall threat.

Current Threat Environment

These various terrorism trends have resulted in a threat environment more complex and diverse than ever before. In the past 2 years, al Qaeda, its affiliates, and HVEs all have attempted attacks on the homeland. New tactics and tradecraft have emerged that further complicate the myriad threats facing the United States. The Internet has allowed terrorist groups to overcome their geographic limits and plays an increasing role in facilitating terrorist activities. In this diffuse and decentralized threat environment, the next attack could come at the hands of a well-trained AQAP operative equipped with a sophisticated improvised explosive device (IED) or a lone HVE using an automatic weapon to attack a shopping mall.

“Despite setbacks to its training program due to the loss of key leaders and an increasingly difficult operating environment, al Qaeda has continued to recruit and train potential operatives.”

Al Qaeda’s Persistent Threat

One of the most significant recent changes to al Qaeda comes with the death of Bin Ladin. Although the full ramifications of his demise are not known yet, the U.S. government continues to assess and monitor how his death affects al Qaeda’s organization and operations. Because of Bin Ladin’s stature and his personal connections with leaders of al Qaeda affiliates and allies, his demise also may change the way these groups relate to one another.

The past 10 years have demonstrated that despite the counterterrorism efforts against al Qaeda, its intent to target the United States remains steady. For example, one al Qaeda homeland plot involved three operatives—Najibullah Zazi, Zarein Ahmedzay, and Adis Medunjanin—who were disrupted by the U.S. government in fall 2009. These individuals received training in Pakistan from al Qaeda and then returned to the United States, where they planned to use homemade IEDs to attack the New York City subway system.

The 2009 plot also demonstrated al Qaeda’s continuation of targeting trends that evolved over the previous years, such as its interest in Western re-cruits for a homeland plot, its preference for IEDs constructed locally, and its desire to target transit infrastructure. Although these aspects of al Qaeda’s modus operandi have remained consistent, al Qaeda has expanded and diversified its strategy in hopes of perpetrating more attacks. For example, while al Qaeda remains committed to large-scale attacks, it also may pursue smaller, less sophisticated ones that require less planning and fewer resources and operational steps. Instead of plots reminiscent of 9/11 that involve more than a dozen operatives, they now may employ only a few.

Rise of Affiliates

While Bin Ladin’s death represents an important victory in U.S. counterterrorism efforts, it does not mean a reduced terrorism threat. The threat from al Qaeda affiliates, like AQAP and Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), has drastically changed and represents the most significant difference in the terrorist threat environment since 9/11. AQAP, which has attempted two homeland attacks within the past 2 years, now poses as serious a threat to the homeland as core al Qaeda. AQAP has proven itself an innovative and sophisticated enemy capable of striking beyond the Arabian Peninsula. While the tactics core al Qaeda developed and refined continue to threaten the United States, the inventive tactics created by AQAP pose an additional dangerous threat.

With the Christmas Day 2009 attempt by Nigerian national Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab to detonate an IED onboard Northwest Flight 253, AQAP became the first al Qaeda affiliate to attempt an attack on the homeland. With this attack, AQAP broke from al Qaeda’s typical modus operandi in several ways. Abdulmutallab was a single operative traveling alone. Rather than constructing his device in the target country, he carried an IED on his person all the way from the flight he first boarded in Africa to the airspace over Detroit, and he evaded detection systems in various airports. Unlike Zazi, Abdulmutallab was not based in the United States, providing fewer chances for the FBI to look for clues of possible terrorist associations.

After this attempted attack, AQAP revealed its capacity to adapt and innovate by following with the October 2010 package-bomb plot. With this plot, AQAP obviated the need for a human operative by sending sophisticated IEDs concealed in printer cartridges inside packages aboard airfreight airlines. This tactic eliminated the potential for human error in the operation or detonation of the device. AQAP claims the total operation cost was only $4,200, a vastly smaller figure than the estimated $400,000 to $500,000 spent by al Qaeda to plan 9/11. In this “death by 1,000 cuts” approach, AQAP moved the West to spend many times that to reexamine and strengthen its security procedures. From AQAP’s perspective, this failed attempt was a success—not in producing mass casualties, but in achieving a high economic cost.

In addition to conducting its own attacks, AQAP also has sought to radicalize and inspire others to conduct attacks. In July 2010, AQAP published the first edition of its English-language online magazine, Inspire, a glossy, sophisticated publication geared to a Western audience. In the five published editions of Inspire, AQAP has provided religious justification and technical guidance, including information on manufacturing explosives and training with an AK-47, to encourage HVEs to stage independent attacks.

In all facets of its operations, AQAP benefits from the expertise and insights provided by its American members to target an English-speaking audience. Anwar al-Aulaqi—a former U.S.-based imam and now a leader of AQAP—is a charismatic figure with many English-language sermons available online. Over the past few years, Aulaqi has gone from a radicalizer to an individual who now plays an increasingly operational role in AQAP. He has recruited individuals to join the group, facilitated training at camps in Yemen, and prepared Abdulmutallab for his attempted bombing of Northwest Flight 253. Samir Khan, an American jihadist blogger who traveled to Yemen in October 2009, helps oversee AQAP’s production of Inspire magazine. Together, Aulaqi and Khan have drawn on their understanding of the United States to craft a radicalizing message tailored to American Muslims.

AQAP is not the only al Qaeda affiliate to pose an increased threat to the homeland. Tehrik-e Taliban (TTP)—a Pakistani militant group that has voiced its desire since 2008 to strike the United States—demonstrated for the first time its ability to stage attacks against America with Faisal Shahzad’s failed VBIED attack on Times Square in May 2010. Shahzad, a naturalized U.S. citizen of Pakistani origin, traveled to Pakistan to acquire terrorist training from TTP and then used those skills to construct a VBIED when he returned to the United States.

Other al Qaeda allies and affiliates also have expanded their focus. In July 2010, Somalia-based terrorist group al-Shabaab staged its first attack outside of Somalia with an attack in Uganda that killed dozens. Al-Shabaab also has attracted Western recruits, including Americans; at least two dozen have traveled to Somalia to train or fight over the past few years. Some of these Americans even have assumed leadership positions, raising the possibility that they could help expand al-Shabaab’s global reach.

As these examples show, the rise of al Qaeda affiliates presents an increasingly complex terrorism threat. U.S. authorities no longer can prioritize al Qaeda threats over those emanating from affiliate groups; they now must cover them all.

Increasing Threat from HVEs

In addition to these external threats, the United States faces a serious threat from HVEs inside its borders. The disruptions over the past several years reveal that HVEs come from a diverse set of backgrounds, ages, and life experiences. HVEs support terrorism in a variety of ways, from traveling overseas to fight to plotting attacks inside the United States.

In 2009, HVEs conducted their first successful attacks inside the United States. The most lethal occurred on November 5, 2009, when the Fort Hood military base was attacked by what appeared to be a lone gunman, killing 13 and wounding 43. The suspected shooter, Major Nidal Malik Hasan, is believed to have acted alone and used small arms to conduct his attack—factors that underscore the difficulty in intercepting HVEs.

Further complicating the HVE threat is their adept use of the Internet, which serves as a facilitator for terrorist activity and a platform for radicalization. Previously, the Internet was used primarily to spread propaganda; today, it facilitates recruitment, training, and fund-raising activities and allows HVEs to overcome their geographic isolation to connect with other like-minded extremists. The disruption of at least three HVEs plotting homeland attacks during 2010 serves as a reminder that their threat shows no signs of abating.

Conclusion

The threat environment has transformed significantly since 9/11 and will continue to evolve over the months and years ahead. While the FBI’s number one priority holds constant—to prevent, deter, and disrupt terrorist activities—the ways in which it accomplishes this mission must not.

To better position itself to adapt to this changing threat environment, the FBI is undergoing a transformation in the way it collects and uses intelligence. The bureau is implementing a new proactive, intelligence-driven model that enables it to develop a comprehensive threat picture and enhances its ability to prioritize resources to address and mitigate terrorist threats.

The FBI also continues to enhance its relationships with intelligence and law enforcement partners at all levels of government and abroad. These national and international collaborative counterterrorism efforts have played a key role in enabling the bureau to thwart myriad terrorist threats over the past decade. To echo the words of FBI Director Robert Mueller III, “working side by side is not only our best option, it is our only option.”

While 10 years have elapsed since 9/11 and much has changed during that time, the sense of urgency that the FBI brings to its counterterrorism mission has not waned. Today, the United States faces a threat environment more complex and dynamic than ever before. And, yet, as new terrorist threats evolve, the FBI will adapt to confront them.

Ms. O’Brien is an intelligence analyst in the FBI’s Counterterrorism Analysis Section.

“In addition to al Qaeda-affiliated groups, the United States also saw the emergence of a generation of unaffiliated individuals inspired by al Qaeda’s ideology but lacking ties to any foreign terrorist organization.”