Predictive Policing: Using Technology to Reduce Crime

By Zach Friend, M.P.P.

Nationwide law enforcement agencies face the problem of doing more with less. Departments slash budgets and implement furloughs, while management struggles to meet the public safety needs of the community. The Santa Cruz, California, Police Department handles the same issues with increasing property crimes and service calls and diminishing staff. Unable to hire more officers, the department searched for a nontraditional solution.

In late 2010 researchers published a paper that the department believed might hold the answer. They proposed that it was possible to predict certain crimes, much like scientists forecast earthquake aftershocks. An “aftercrime” often follows an initial crime. The time and location of previous criminal activity helps to determine future offenses. These researchers developed an algorithm (mathematical procedure) that calculates future crime locations.1

Equalizing Resources

The Santa Cruz Police Department has 94 sworn officers and serves a population of 60,000. A university, amusement park, and beach push the seasonal population to 150,000. Department personnel contacted a Santa Clara University professor to apply the algorithm, hoping that leveraging technology would improve their efforts. The police chief indicated that the department could not hire more officers. He felt that the program could allocate dwindling resources more efficiently.

Santa Cruz police envisioned deploying officers by shift to the most targeted locations in the city. The predictive policing model helped to alert officers to targeted locations in real time, a significant improvement over traditional tactics.

Making it Work

The algorithm is a culmination of anthropological and criminological behavior research. It uses complex mathematics to estimate crime and predict future hot spots. Researchers based these studies on information that officers inherently know. For example, when people are victims, the chance that they or their neighbors will be victimized again increases. Offenders criminalize familiar areas. There are detectable patterns associated with the times and locations of their crimes.

Mr. Friend is a crime analyst with the Santa Cruz, California, Police Department.

Using an earthquake aftershock algorithm, the system employs verified crime data to predict future offenses in 500-square-foot locations. The program uses historical information combined with current data to determine patterns. The system needs between 1,200 and 2,000 data points, including burglaries, batteries, assaults, or other crimes, for the most accuracy. Santa Cruz, averaging between 400 and 600 burglaries per year, used 5 years of data.

Throughout the experiment the Santa Cruz Police Department focused on burglaries— vehicular, residential, and commercial—and motor vehicle thefts.2 The system works on gang violence, batteries, aggravated assaults, drug crimes, and bike thefts. It functions on all property crimes and violent crimes that have enough data points and are not crimes of passion, such as domestic violence. Homicides generally do not provide enough data points to produce accurate predictions.

Using the Data

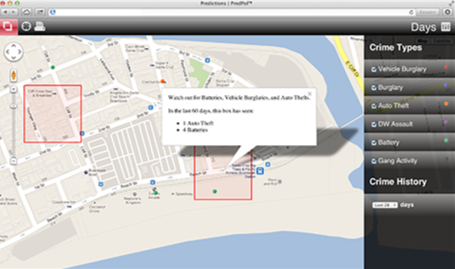

To add an extra layer of security, employees transfer the data on designated crime types from the records management system (RMS) to the secure Web-based system. The algorithm requires the date, time, type, and location of a crime. This is public data, which adds another level of security in case someone intercepts the information. No one submits, collects, or uses personal data. The system processes the information through the algorithm and combines it with historical crime data to make predictions.

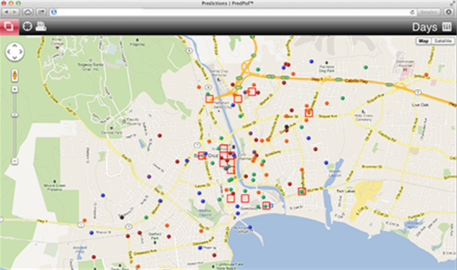

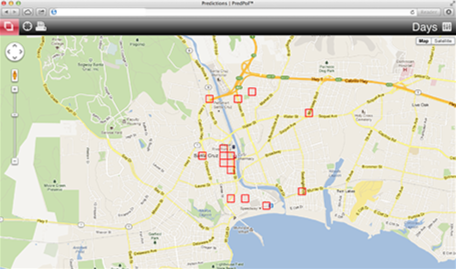

Staff members log in, just like they do on an e-mail account, and the system generates hot spot maps. For Santa Cruz police, there are 15 hot spot maps per shift. Distributed through roll calls, these maps indicate 500-square-foot locations. Officers pass through these areas when they are not obligated to address other calls. No one dispatches or requires them to patrol the sites; they do it as part of their routine extra checks. Some agencies using the program designate predictive policing units to run patrols, while others use unmarked cars to traverse hotspots.

The Santa Cruz Police Department decided not to mandate the patrols. Personnel thought it would eliminate the feeling of an administrative directive and empower officers to be as proactive as their call levels allowed. When police enter and clear the hot spot locations, they notify dispatch with a designated clearing code. This enables dispatch personnel to collect data on the frequency of the officers’ presence in the hot spots.

Evaluating the Process

During the first 6 months of the program, the department made over 2 dozen arrests within the hot spot locations. However, the true measure of the program’s success is not apprehensions, but the reduction of crime. Santa Cruz police officers indicated an initial 11 percent reduction in burglaries and a 4 percent decrease in motor vehicle thefts. As time progresses, the reductions increase. Over a 6-month period, burglaries declined 19 percent.

The system requires 6 months of data to assess whether the method actually is reducing the crime rate. Because the Santa Cruz police did not introduce any additional variables—no additional officers were hired, shift lengths continued, patrol structure remained the same—the department attributed the crime reduction to the model.

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) tested the method under a controlled experiment. The project scientifically proved the model’s effectiveness. The city has a larger population and more complex patrol needs than Santa Cruz. Researchers established the experiment in the Foothill Division with a population of 300,000 people. They compared the predictive policing system with LAPD’s best practices.

Similar to the Santa Cruz test, the department distributed maps to officers at the beginning of roll call. On some days analysts produced the maps using traditional LAPD hot spot methods. On other days, they used the algorithm. No one told the officers where the maps came from. Graphically they looked the same.

The algorithm provided twice the accuracy that LAPD’s current practices produced. While property crime was up .4 percent throughout Los Angeles, Foothill’s declined by 12 percent. Foothill benefitted from the largest crime reduction of any division during the experiment.

People found it hard to understand that an algorithm performed similar to a crime analyst. Eventually, even the most skeptical individuals realized that the method worked. The LAPD expanded the program to other divisions serving a total population of over 1.5 million people. Each one that implemented the predictive policing software achieved crime reduction. The department recognized that the predictive policing system is a large improvement over previously used approaches. When looking at a map from 1 week, the assumption is that the next week will be the same. The computer eliminates the bias that people have.

Gaining Support

As with any new program, questions and concerns arise. People resist change. The Santa Cruz Police Department worked with officers to develop maps and solicit feedback before implementation of the program. The department emphasized that the program does not replace officer intuition but supplements it.

The Santa Cruz Police Department found that veteran officers usually identify 8 or 9 of the 15 hot spot locations. Newer officers discover 1 or 2 of the areas. This validates skilled police officers’ intuition, provides additional targeted locations, and imparts tactical information for new officers. The maps reinforce existing knowledge and inform about targeting locations. They standardize information across shifts and experience levels.

The algorithm combines historic and daily crime information, produces real-time predictions of areas to patrol, and normalizes information among shifts. It eliminates the concern about adequate information sharing. Officers obtaining the daily hot spot maps receive any information they missed due to vacation, illness, or regular days off.

The program shares information graphically. It does not replace the value of senior officers teaching younger ones or the need for roll calls to discuss crime trends. It cannot replace police officers’ knowledge and skills and does not remove the officer from the equation. It puts law enforcement in the right time and place to prevent crime.

Conclusion

Additional departments in the states of California, Washington, South Carolina, Arizona, Tennessee, and Illinois have implemented the program. In November 2011 Time Magazine named predictive policing one of 50 best inventions for 2011.3 The Santa Cruz police chief acknowledged the recognition, but said the accolades are less important than the crime reduction. According to the chief, “Innovation is the key to modern policing, and we’re proud to be leveraging technology in a way that keeps our community safer.”4

Endnotes

1 Dr. George Mohler, Santa Clara University, California, and Dr. P. Jeffrey Brantingham, University of California at Los Angeles, California, developed the algorithm (mathematical model) for predictive policing.

2 George Mohler, P. Jeffrey Brantingham, and Zach Friend conducted the research in Santa Cruz, California.

3 Lev Grossman, Cleo Brock-Abraham, Nick Carbone, Eric Dodds, Jeffrey Kluger, Alice Park, Nate Rawlings, Claire Suddath, Feifei Sun, Mark Thompson, Bryan Walsh, and Kayla Webley, “The 50 Best Inventions of 2011,” Time Magazine, November 28, 2011. www.time.com/time/ magazine/article/0,9171,2099708-13,00.html (accessed September 27, 2012).

4 Santa Cruz Police Chief Kevin Vogel.