Perspective

Police Officer Wellness Training: The Road to Mental Readiness

By Irene Barath

In October 2012 the Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario, Canada, released a report titled In the Line of Duty that documented the impact of operational stress on law enforcement officers.1 It recommended a framework for changes, some the Ontario Police Department already commenced.

Common themes emerged from officers who experienced operational stress injuries (OSI). The most predominant indicated that stigma relating to psychological illness remained entrenched and pervasive within the ranks.2 The second-most prevalent topic examined proactive assistance for officers to develop resilience skills and wellness practices, rather than a focus on an injury-based model.3

Assessing the Problem

An investigation into current instructional resources within American and Canadian law enforcement and military organizations addressed the stigma associated with OSIs. Individuals must recognize an OSI as a viable injury, not an excuse. Education on the subject has progressed; however, more organized training remains necessary.4

For years following the release of the ombudsman’s report, Canadian emergency services personnel experienced crises. Between April 29 and December 31, 2014, 27 public safety workers committed suicide; in 2015, 40 more died the same way.5 These losses bear significance, especially when considering the vast resources available to these individuals.

Communities must discover solutions for themselves by 1) recognizing that a serious-enough problem exists to warrant collective attention; 2) addressing the issues; 3) detecting positive deviances; and 4) disseminating findings through action.6 The Ontario Police College (OPC) examined best practices for American and Canadian law enforcement and military personnel and compared each organization’s activities with those in similar agencies.7 The process led OPC and Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services (MCSCS) partners to the Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) model used by the Canadian Department of National Defense (DND) as part of its mental health and wellness strategy.8

Ms. Barath is an instructor in the Leadership Development Unit of the Ontario Police College in Aylmer, Ontario, Canada.

Developing the Training

In 2008 DND established the R2MR program at the request of the chief of military personnel and the surgeon general in response to concerns for the mental health and well-being of individuals who deployed to and returned from Afghanistan. This included uneasiness regarding the lack of training to prepare for the challenges of deployment and combat operations.9

Mental health specialists provided research and psychological and social perspectives, and operational military personnel and their families prepared material for themselves and their peers. Together, they adopted R2MR. During development of this program, DND personnel met with members of the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Navy Seals to examine their training on resilience-building skills.

Evidence-based R2MR training applies accomplishments in sports psychology, neuroscience, and resilience training. DND leaders integrated this model and supporting materials into their program, including specialized instruction and deployments. Officials in DND conducted evaluations to determine the impact on the psychological wellness of their personnel. Results indicated that the training increases mental health knowledge and resilience skills while it decreases stigma and negative attitudes toward seeking help.10

DND instituted R2MR training with clear guidance, which it still maintains.11

- Target the training to both operational and nonoperational mental health conditions.

- Focus on traumatic and nontraumatic pressures from operational, occupational, and personal stressors.

- Create a positive expectancy for recovery from setbacks, and reinforce that many people manage demands using their existing coping skills.

- Keep training simple and consistent to create a common understanding in language and meaning.

- Monitor and evaluate current research to maintain the best program possible.12

Almost simultaneous to OPC’s research, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) created a stigma-reduction program and discovered the work in progress by DND on R2MR training.13

Launching New Initiatives

In October 2009 MHCC launched an initiative to reduce the embarrassment and discrimination associated with mental health issues and create a culture shift centered on contact-based education.14 Through this proposal, individuals who successfully managed mental conditions engaged peers in discussion regarding the impact of stigma and bias and encouraged help-seeking behaviors.

MHCC recognized R2MR’s potential and collaborated with Canadian law enforcement agencies to adapt materials for police personnel, both sworn and unsworn. In September 2014 it used feedback from law enforcement and civilian pilot groups to develop two standardized R2MR training packages. A 4-hour-long primary course focuses on frontline operational officers, and an 8-hour class centers on leaders’ responsibilities as they address their own personal mental health awareness and impact on employees.

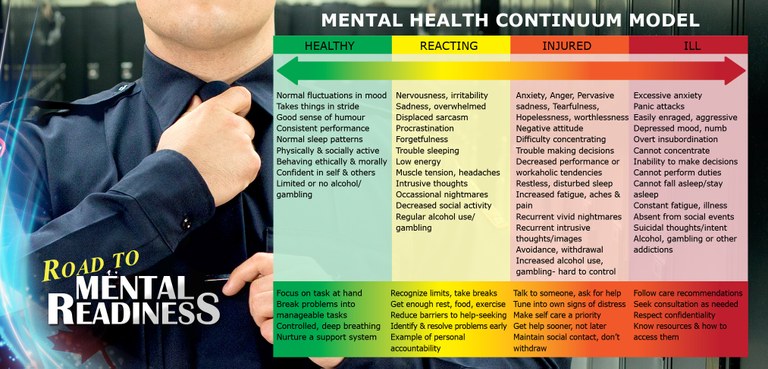

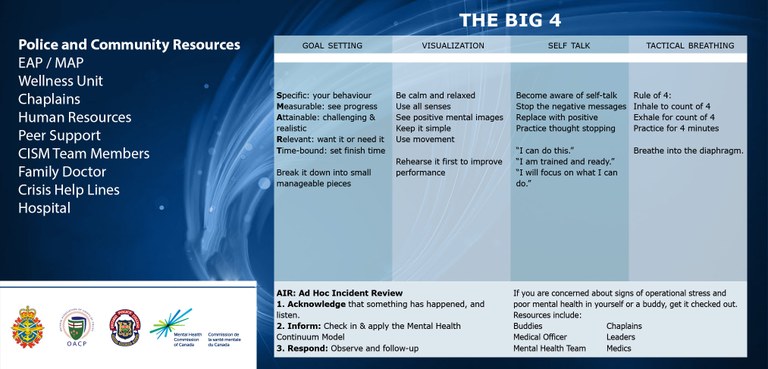

OPC trained instructors to teach classes that introduced staff to the Mental Health Continuum Model and The Big 4 resilience skills that proactively support their psychological well-being.15 In January 2015 they incorporated R2MR into the 12-week Basic Constable Training (BCT), which is similar to military basic training. BCT is challenging and stressful as students progress from civilians to professional police officers. Integration of R2MR with BCT potentially reduces discomfiture and begins the culture shift related to mental health and wellness.

Building the Program

The standardized format for the primary R2MR program includes 1) stigma and barriers to care; 2) mental health in the workplace; 3) comprehension of stress responses; 4) the Mental Health Continuum Model; 5) The Big 4 resilience skills; and 6) successful resources at work.16 The first three modules establish an understanding of mental health and solutions for challenging the stigma and removing barriers to care. The remaining units focus on mental health awareness and its impact on people’s lives through mood changes, thoughts, attitudes, behaviors, performance, and physical wellness. These sections also explore the benefits of resilience skills and knowledge of resources available within law enforcement organizations.

Using the Mental Health Continuum Model

The Mental Health Continuum provides visual representation and common language to describe observable behaviors and reinforce mental health concepts. An arrow on the continuum goes both left and right, indicating that people can shift away from mental well-being, but return to that state with appropriate intervention. The model reinforces that both mind and body systems require maintenance. The continuum denotes progression from healthy to reacting, then injured, and, finally, to ill, then back through the process to return to healthy, serving as a reminder that awareness accompanied by early intervention provides positive effects on mental health.

This continuum supplies a common language to help individuals understand their own mental health status and remain aware so they can support others. Because some people cannot verbalize that they are reacting, injured, or ill, the scale applies a color-coded system that enables individuals to respond to questions by using colors instead of words. For example, rather than a person saying they suffer anxiety or feel injured, they could state that they currently experience “orange.” People learn not to label their colleagues as healthy or ill because the continuum and clear common language indicate that individuals often remain productive and engaged while managing mental health challenges.

Teaching The Big 4

With a wellness-focused approach, the R2MR program provides participants with resilience skills called The Big 4—goal setting, visualization, self-talk, and tactical breathing. This skill set conforms to many aspects of sports psychology and improves the training pass rate of specialized military candidates. During R2MR training, participants regularly discuss and practice The Big 4 to reinforce their benefits.

The primary program within the leadership training includes emphasis on the responsibility of leaders to address mental health issues. Supportive management correlates with the financial health of the organization, as well as its ability to recruit and retain talent.17 It also links to employee well-being, work-life conflict, the perception of work overload, and the feeling of a time crunch.18 Further, such management serves as a key predictor of employee turnover, job satisfaction, commitment, and absenteeism.19

Management support involves creating a culture of respect and inclusivity and stressing that no tolerance exists for stigma and discrimination. When leaders establish an open, trusting workplace, they reduce barriers to care and enable staff to maintain mental health through resilience skills and help-seeking behaviors.

Research indicated that officers who felt respected by their supervisors more readily accepted and voluntarily complied with department policies, which encourages officers to seek help without worrying about consequences.20 The structured and consistent messaging of R2MR materials helps the MHCC reach its objectives to 1) improve mental health and resilience; 2) mitigate effects of stressful work environments; 3) reduce stigma; 4) ensure respectful and inclusive workplaces; and 5) encourage individuals to seek help in the early stages of declining mental health.21

Employing the Positive Deviance Approach

R2MR training correlates with the Positive Deviance Approach.22 This methodology presents a problem-solving process that requires individuals to retrain themselves to pay attention differently, awakens minds accustomed to overlooking outliers, and cultivates skepticism regarding the common “that is just the way it is” response.23

OPC used the Positive Deviance Approach to build on innovative work already done to bring R2MR training to police service personnel in Ontario.24 This model comprises underlying foundations that recognize 1) solutions to seemingly difficult problems already exist; 2) community members can discover answers themselves; and 3) innovators may succeed even though they share the same barriers and constraints as others.25 Success of this model mirrors that of other police and emergency services stakeholders.

Providing a Status Update

In 2014, 10 Canadian police agencies instituted R2MR and a pilot of the first instructor’s course. Organizations screen potential trainers through a comprehensive process based on successful management of the individual’s own mental health, previous training experience and adult education certifications, peer recommendations and support, prior mental health training, and any other relevant instruction. Before delivering the course, the agency must strengthen the supportive infrastructure to ensure people who come forward and seek assistance receive quick referrals to the appropriate resources.

The Positive Deviance Approach proves unsuitable for some purposes. However, it excels over most alternatives for addressing problems enmeshed in complex societal systems, requiring behavioral and social change, and entailing solutions with unforeseeable or unintended consequences.26 One of the unpredictable results involves the number of people who may decide they want to return to a healthy place while continuing to work hard and engage productively in the workplace. This could tax existing resources or identify gaps where they are nonexistent.

Conclusion

Law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve must recognize issues concerning mental health and well-being of officers. By proactively working together, they can reduce the stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness and encourage help-seeking behaviors. The Canadian Department of National Defence developed the Road to Mental Readiness program to address these problems. This training presents one example of a resource organizations can use to begin the difficult and challenging conversations regarding mental health.

For additional information Ms. Barath can be reached at irene.barath@ontario.ca.

Endnotes

1 Ontario, Canada, Office of the Ombudsman, Ombudsman’s Report: In the Line of Duty, Andre Marin, October 2012, 80, accessed June 20, 2016, https://www.ombudsman.on.ca/Files/ sitemedia/Documents/Investigations/SORT%20Investigations/OPP-final-EN.pdf.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., 88.

5 Vince Savoia, “Canadian Public Safety Suicides by Province,” Tema Conter Memorial Trust, accessed June 21, 2016, https://infogr.am/canadian_first_responder_suicides_by_province.

6 Richard Pascale, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin, Power of Positive Deviance (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2010), 3, 12-13.

7 Linda Duxbury and Christopher Higgins, Caring For and About Those Who Serve: Work-Life and Employee Well-Being Within Canada’s Police Departments (Ontario, Canada: 2012), accessed June 21, 2016, http://sprott.carleton.ca/wp-content/files/Duxbury-Higgins-Police2012_ fullreport.pdf.

8 “Road to Mental Readiness Secondary Trainer Information and Application,” Ontario Association of Fire Chiefs, accessed June 21, 2016, http://www.oafc.on.ca/road-mental-readiness-secondary-trainer-information-and-application.

9 Irene Barath, “Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) Trainer Materials,” (presentation, Canadian Department of National Defence and Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2015); see also “Road to Mental Readiness Secondary Trainer Information and Application.”

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Duxbury and Higgins.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Charles H. Ramsey and Laurie O. Robinson, Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015), 62, accessed June 22, 2016, http://www.cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/taskforce/taskforce_finalreport.pdf.

21 Barath, “Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) Trainer Materials.”

22 Pascale, Sternin, and Sternin.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.