Case Study

The Hosam Smadi Case: An Example of Success

By Thomas D. Petrowski, J.D.; Michael W. Howell, M.A.; David W. Marshall; and Sheeren Zaidi, M.S.

On September 24, 2009, 19-year-old Jordanian national Hosam Maher Hussein Smadi parked what he believed to be a large vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) in the underground garage of Fountain Place—a beautiful, conspicuous skyscraper in the heart of the Dallas, Texas, business district. He armed and powered up the elaborate timing device, exited the building during the busy weekday lunch rush, and was picked up by an associate who he believed was a low-level soldier in the al Qaeda cell he had located after a long search.

With the associate, Smadi drove to the top of a nearby parking garage where he used his mobile phone to dial the number that he believed would detonate the VBIED—he had insisted on personally command-detonating the bomb—and destroy the building, killing thousands of innocent civilians in and around Fountain Place. The call, however, did not activate an VBIED; instead, it signaled the North Texas Joint Terrorism Task Force to arrest Smadi while he attempted to commit mass murder in the name of al Qaeda.

Smadi had spent months planning the attack, modifying his plans as to which target he would focus on and what type of explosive device he would use. He believed he was fortunate to have found in the United States an al Qaeda sleeper cell planning the next large-scale attack and that he could convince the cell to let him commit an enormous act of terrorism as an al Qaeda soldier.

In fact, Smadi had not found an al Qaeda sleeper cell but an FBI undercover operation (UCO) conducted by the Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) operating out of the FBI’s Dallas, Texas, division, one of 106 JTTFs across the country. The Smadi investigation represents an excellent example of the results of one of the current national counterterrorism strategies of the JTTF—in this case, critical member agencies included the Dallas, Texas, Police Department and the Texas Department of Public Safety—to identify and neutralize lone terrorists in the United States. The investigation also highlights the growing threat of lone offenders who operate without any ties to terrorist groups or states, can become radicalized by propaganda easily found on the Internet, and increasingly exist in America’s rural areas.

Fountain Place, a 60-story high-rise building in Dallas, Texas. It is the 15th tallest building in Texas and houses over 1,200 employees.

Facing Challenges

The U.S. government’s counterterrorism mission has many challenges, the most difficult being to preemptively identify lone-offender terrorists, individuals with no direct connection to a terrorist organization but who have been self-directed in their pursuit of radicalizing influences. These lone-offender terrorists typically become known only after an attack. Recent examples include Nidal Malik Hasan, charged with killing 13 and wounding 32 at Fort Hood, Texas; Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad, accused of killing a man at a recruitment center in Little Rock, Arkansas; Andrew Joseph Stack, who flew his plane into a Texas IRS building; James von Brunn, who allegedly killed a security guard at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.; and Scott Roeder, sentenced to life in prison for murdering a doctor who performed abortions.1 More well-know lone offenders include Timothy McVeigh, Ted Kaczynski, and Eric Robert Rudolph.

The FBI, the U.S. Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and numerous outside experts assess that the homegrown, lone-offender terrorist, such as Smadi, proves the most difficult to identify and likely will become more common in the West as extremist ideologies spread globally.2 English-speaking Islamic extremists are increasing their use of the Internet to recruit and radicalize Western Muslims and converts.

Carrying out the U.S. government’s counterterrorism mission requires a preemptive strategy so threats can be interdicted before they manifest into a terrorist attack. In response to this challenge, the FBI has created several initiatives designed to identify the lone offender, including some programs that are cyber based, not unlike the Innocent Images National Task Force in the Crimes Against Children Program.3 They seek out those who may be lone-offender terrorists or on the path of radicalization.4 Smadi was identified through one of these initiatives, illustrating a significant success in these identification programs that provides an outstanding model for similar counterterrorism cases.

Identifying Smadi

In January 2009, the FBI’s Chicago field office discovered Smadi within an online group of extremists where the FBI maintained an undercover presence. Unlike many others in the group who espoused and endorsed violence, Smadi stood out based on his vehement intention to conduct terror attacks in the United States and because of his zealous devotion to Usama Bin Ladin and al Qaeda. The FBI initiated a terrorism investigation to assess whether he posed a tangible threat to national security.5 After Smadi repeated these comments, the undercover program made online contact with him. During those communications, Smadi made clear his intent to serve as a soldier for Usama Bin Ladin and al Qaeda and to conduct violent jihad (acts of terrorism in the name of Islam) in the United States.

FBI Dallas quickly determined that Smadi was a citizen of Jordan, illegally residing in the United States in rural Italy, Texas, where he worked as a clerk at a gas station and convenience store. He entered the United States on March 14, 2007, on a nonimmigrant B1/B2 visa (temporary visitor for business or pleasure) that expired on October 30, 2007. Smadi was in violation of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) when he overstayed his visa and, therefore, was deportable at any time.

Establishing the Undercover Operation

The FBI JTTF in Dallas stood up a complex sting operation in which Smadi believed he had found in the United States an al Qaeda sleeper cell planning the next large-scale attack.6 Smadi believed he was in online contact with a senior member of the cell and continued to communicate his intent to commit an act of terrorism in the United States despite consistent attempts by undercover agents to dissuade him.7

After approximately 3 months and 25 online covert conversations with Smadi, the JTTF determined the UCO would transition to an in-person context to allow a more accurate assessment. Another FBI undercover agent in the role of a lower level operational soldier in the sleeper cell was introduced to Smadi, who remained in online contact with who he believed to be the senior leader of the cell.

All authors served on the joint terrorism task force responsible for the Hosam Smadi investigation.

Special Agent Petrowski is a supervisor in the FBI’s Dallas, Texas, office.

Special Agent Howell is assigned to the FBI’s Dallas, Texas, office.

Special Agent Marshall is assigned to the FBI’s Dallas, Texas, office.

Ms. Sheeren Zaidi is an intelligence analyst in the FBI’s Dallas, Texas, office.

Administratively, the UCO was both difficult and burdensome. As a national security UCO, the entire investigation was classified. Virtually all communications with Smadi were in Arabic, his native language (all three undercover agents also were native Arabic speakers). Every communication with Smadi was electronically recorded, and the in-person meetings between Smadi and the undercover employees were recorded through multiple recorders and video. Meticulously recording and documenting all communications with Smadi proved critical because of the inevitable entrapment defense raised during prosecution.

Assessing Smadi as a Threat

From the day the FBI identified Smadi, the agency analyzed intelligence to assess his potential as a unilateral threat and lone offender with no direct connections to a terrorist organization. Behavioral Analysis Unit experts from FBI Headquarters were brought into the investigation to help assess what, if any, threat he posed. Within a few months, the FBI assessed that Smadi was a self-directed Sunni extremist, lone offender determined to commit an act of terrorism on the scale of the 9/11 attacks. He also was assessed to be obsessed with Usama Bin Ladin and the idea of being a soldier of al Qaeda.8 Because of this and the prospect of his belief that he actually contacted al Qaeda, it was likely he would not do anything impetuous. The challenge was keeping the investigation secret. If he ever realized his sleeper cell actually was a sting operation, he likely would have done something very violent, very quickly.

Investigation revealed that Smadi was not a practicing Muslim and was not affiliated with a mosque or the mainstream Islamic community in north Texas. He stated to the undercover agents numerous times that “they” (his family and the local Islamic community) “don’t get it,” that they did not share his extremist, violent view of jihad. Postarrest interviews of the extended family indicated they were outstanding members of the Dallas Islamic community, gainfully employed and regular members of a large local mosque. Smadi’s estrangement from his extended family and the mainstream Muslim community was a significant factor in his assessment as a threat.

Addressing Smadi

By summer 2009, Smadi’s inevitable and significant threat to the United States had become clear. In evaluating options to interdict the threat, numerous issues were presented. Because Smadi was a Jordanian citizen and illegally in the United States, the easiest choice for quickly addressing the threat Smadi posed was to arrest him on an immigration charge and deport him. While attractive as a short-term remedy, it was clear he was going to commit an act of terrorism against U.S. interests at some point. Deporting him would only move that threat overseas, not terminate it. Overseas, Smadi likely would have found members from al Qaeda or another terrorist organization (as he said he would do if he lost contact with his perceived sleeper cell). The FBI assessed that if he came in contact with these terrorists overseas, they would have provided him with false identification so he could return to the United States to conduct attacks.

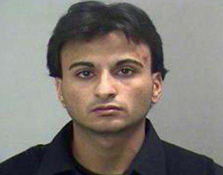

Smadi—still photo from his 7-minute video to Usama Bin Laden

The possible courses of action to address the threat Smadi posed were limited. Conspiracy charges, often used to take down a group or an individual associated with a group planning an attack, were not available as he was acting as a lone offender. After lengthy consultations with prosecutors in Dallas and the U.S. Department of Justice, the only viable strategy was to give Smadi what he sought: the opportunity to perpetrate the terrorist attack he was planning in a controlled manner and then prosecute him for that attempt.

Conducting the UCO

The UCO lasted approximately 9 months. Despite consistent efforts to dissuade Smadi throughout the operation, his planning and actions showed unrelenting determination to commit a large-scale terrorist attack on American soil as a soldier of al Qaeda.

During one of the later in-person meets, the undercover agent indicated that the cell had the capability to forward a video of Smadi to Bin Ladin. Smadi was emotionally overwhelmed. He spent hours researching on his computer and drafting a statement. With surreptitious cameras recording in the hotel room where they met, the undercover agent set up a tripod and video camera and made the recording. Smadi covered his face and made a compelling 7-minute video for Bin Ladin, which he believed would be delivered to the al Qaeda leader after Smadi’s attack. The video resulted in one of the most compelling pieces of evidence against him.

The Smadi UCO shared many common issues with typical undercover operations: maintaining the integrity of the operation, ensuring the safety of the undercover agents, resolving translation issues, and addressing entrapment. Eventually, a total of six in-person meetings and about 65 online and telephonic communications occurred. An additional issue with running long-term UCOs targeting active terrorists is the constant concern that the subject is moving about freely in America, which creates perpetual physical and technical surveillance challenges.

Smadi—surveillance photo

Smadi—booking photo

Planning by Smadi

Through spring 2009, Smadi, on his own, was aggressively conducting research, physical reconnaissance, and analysis of targets he wished to attack. His first plans involved targeting large credit card companies (he indicated hope this might further harm the ailing economy). He also said he was considering military targets and the baggage claim area of a Dallas airport. His initial plans also focused on him planting smaller explosives at multiple locations, which he believed would have a more dramatic effect.

After months of researching targets, Smadi decided to confine his plan to using a sizable explosive to attack one large target. By late June, Smadi had made several selections and then changed those targets either because they were too secure or not big enough. He put a significant amount of individual effort into developing and refining his planned attack. He settled on a 60-story building in downtown Dallas known as Fountain Place and asked his perceived sleeper cell to make him a car bomb big enough to bring down the entire building.

FBI headquarters and Dallas bomb technicians constructed the VBIED Smadi asked for. It included a clock timer, a safe-arm switch, 550 pounds of explosive-grade fertilizer, and inert blasting caps placed within inert C-4 explosive blocks. All of the components of the VBIED were contained within a 2001 sport utility vehicle. The VBIED had been designed to be readily adaptable, yet inert for public safety purposes.

Surveillance indicated that Smadi took several operational steps in the days before his attack that he did not completely share with his perceived al Qaeda associates. On September 22, in preparation for driving the VBIED into the garage and then walking out of Fountain Place, Smadi purchased an elaborate disguise, planning on wearing a cross around his neck and dressing as a parking valet for the day of the attack. The day before the incident, he moved his residence to a rural, isolated trailer in the event he was identified and needed to hide.

“The investigation... highlights the growing threat of lone offenders who operate without any ties to terrorist groups or states....”

Vehicle that housed the vehicle-borne improvised explosive device with the target location in the background.

Vehicle-borne improvised explosive device.

Sentencing Smadi

In May 2010, Smadi pleaded guilty to one count of attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction and was sentenced to 24 years in prison in October 2010. As is typical in UCOs that result in overwhelming evidence against a defendant, Smadi’s defense attorneys argued entrapment and mental health issues early in the prosecution. After discovery was completed, the defense team conceded there was no plausible way for an entrapment defense. The complete rejection of entrapment was a result of the issue being identified early on in the investigation and addressed throughout the case. In virtually every undercover conversation with Smadi, the operation attempted to discourage his planned course, and all communications—written, online, or in person—were recorded.

Conclusion

The Smadi investigation is significant not only because it prevented a terrorist attack but because it serves as a model for future lone-offender terrorism cases. Exposing self-radicalized lone offenders, such as Smadi, is an enormous challenge in preventing terrorism and will only become more common and necessary.

The most significant aspect of the Smadi investigation is that it demonstrates an overall capability of the JTTF to bring to bear the efforts of countless employees in the FBI and partner agencies working together in support of the domestic counterterrorism mission. The capacity to coordinate these entities and partner agencies into a unified effort from the street level to the highest levels in the U.S. intelligence community illustrates the evolving innovation and capability of the FBI, state and local law enforcement, and other agencies involved in the domestic counterterrorism mission.

Endnotes

1 Major Nidal Hasan allegedly committed his attack on Fort Hood on November 5, 2009. Muhammad, aka Carlos Bledsoe, an American convert, attacked a military recruiting office in Little Rock, AK, on June 1, 2009. Stack flew a small personal plane into the IRS building in Austin, TX, on February 18, 2010. Brunn attacked the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC, ostensibly motivated by anti-Jewish hatred. Roeder murdered Dr. George Tiller on May 31, 2009, in church because he was a well-known abortion advocate and provider.

2 U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, A Ticking Time Bomb: Counterterrorism Lessons from the U.S. Government’s Failure to Prevent the Fort Hood Attack, a Special Report (Washington, DC, 2011); http://hsgac.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?FuseAction=Hearings.Hearing&Hearing_ID=9516c9b9-cbd4-48ad-85bb-777784445444 (accessed June 20, 2011). The report noted “[w]e recognize that detection and interdiction of lone-offender terrorists is one of the most difficult challenges facing our law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Every day, these agencies are presented with myriad leads that require the exercise of sound judgment to determine which to pursue and which to close.”

FBI and U.S. intelligence community (USIC) products addressing this point are generally classified. An example of a leading terrorism expert addressing this point consistent with USIC assessments is Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism expert at Georgetown University and previously at the Rand Corporation and the CIA. Hoffman and other leading experts have published works that identify the homegrown, lone-offender terrorist as the hardest to detect and likely to become more common.

Bruce Hoffman, Inside Terrorism (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1999); in this book, Hoffman noted, “the new strategy of al Qaeda is to empower and motivate individuals to commit acts of violence completely outside any terrorist chain of command.”

3 In the national security context, these programs are worked with USIC partners, and virtually all aspects related to them are classified. In keeping this article unclassified, it is impossible to give complete details of the work and accomplishments of these programs. Notwithstanding the sensitivity of these programs, the large majority of the details of the Smadi investigation were declassified for use during the prosecution.

4 In support of the preventive mission of identifying lone-offender terrorists, the FBI has developed a Radicalization Continuum that identifies attributes of these subjects from preradicalization (developing sympathies for a perceived cause) through the final stages of taking action and committing a terrorist act.

5 Like all international terrorism investigations conducted in the United States, the Smadi investigation was completely classified and worked closely with other USIC partners with whom the FBI now freely can exchange information due to the USA PATRIOT Act. For a detailed source on the legal aspects of conducting domestic national security investigations, see David Kris and J. Douglas Wilson, National Security Investigations & Prosecutions (Eagan, MN: Thomson/West, 2007).

6 The FBI Dallas Joint Terrorism Task Force, which conducted this UCO, was comprised of members of the FBI; the U.S. Transportation Security Administration; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; the Dallas, Texas, Police Department; the Garland, Texas, Police Department; and the Texas Department of Public Safety. Run out of the Dallas Division, the UCO was closely managed by the FBI’s Counterterrorism Division collocated with the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) in northern Virginia.

7 Because of the brevity of this article, specific examples of the online communication between Smadi and the undercover employees are not provided. The affidavit submitted in support of the arrest is available at http://www.txnd.uscourts.gov/judges/smadi/smadi.html (accessed July 14, 2011).

8 The FBI assessed with high confidence that the factors that shaped Smadi’s identity as a violent jihadist were the combination of childhood trauma, the Internet, social networking Web sites, Middle Eastern geopolitical issues, and consuming personal identification with Usama Bin Ladin and Abu Mu’sab al-Zarqawi. Smadi is a product of al Qaeda’s global strategy to inspire potential youth recruits and lone offenders in the making through its militant Salafist ideology.