Building Better Candidates Through Technical High Schools

By David Cruickshank, M.S.

It is well-known that law enforcement and related trades will face many recruitment problems over the next several decades. Articles in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin have highlighted these challenges, and most law enforcement executives are looking for new strategies to hire and retain quality personnel in a growing sea of more enticing career options and benefits.1 It seems the greatest marketing tool these days is the proliferation of high-technology crime-solving television dramas that inspire young people to want to be profilers or crime lab analysts.

A teenager is typically motivated to follow the law enforcement career path because of personal experience, perception based on what they see and hear in multimedia, and/or familial influence. One pioneering technical high school in Connecticut has found a way to appeal to all three motivators while building better candidates in the process. Can working with these schools help agencies recruit better candidates?

Background

The Connecticut Technical Education and Career System (CTECS) comprises 17 tuition-free, diploma-granting high schools throughout Connecticut, offering education in 31 career paths, such as veterinary science, automotive repair, electric, plumbing, cosmetology, and culinary arts.

Founded in the early 1900s — before high schools were common and prior to their use as part of a national push for trade schools, brought on by the Connecticut Trade School Act of 1909 and the federal Smith-Hughes Act in 1917 — Connecticut’s technical high school program has remained career-focused to this day.2

Mr. Cruickshank, a former detective, EMT, dispatcher, and executive director of the Law Enforcement Research Group, is the department head and an instructor for the Criminal Justice and Protective Services program in Middletown, Connecticut.

Recently, CTECS recognized that Connecticut would soon be facing critical staffing shortages of police, fire, EMS, corrections, and dispatch personnel and decided to act. In 2017, the first Criminal Justice and Protective Services (CJPS) program opened at Vinal Technical High School in Middletown, Connecticut, to meet the state’s future needs. The program has grown significantly since its inception and today boasts full enrollment with lengthy annual waitlists.

Curriculum

The CJPS program provides high school students with more certifications than most 3- or 4-year officers have earned, while preparing them to be ideal candidates by instilling the importance of effective decision-making throughout their teenage years and the impact that social media can have on their futures.

Students are trained to be problem solvers and certified in a wide range of topics to help them adapt and overcome any scenario.

- CPR

- STOP THE BLEED3

- Hazardous materials

- Incident Command System4

- Report writing

- Constitutional, state, federal, and domestic violence law

- Basic and intermediate crime scene investigation

- Emergency medical technician practices

Students can even earn a Federal Aviation Administration remote pilot certificate to fly public safety drones.

The program is immersive as students are full-time “in shop” for 90 days of the school year, which affords instructors a tremendous amount of time with the students. Many topics not covered in-depth in professional academy settings because of time constraints have been built into the evolving CJPS curriculum, producing better, more-informed candidates. Topics such as dispatch operations, interviewing, warrant authoring, bias and profiling, and de-escalation techniques are comprehensively covered during a student’s 4-year high school education.

Students can also go to work instead of school in their junior and senior years, which further immerses them in the field of criminal justice and protective services. Currently, the program has students working with Connecticut Department of Consumer Protection and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigators conducting undercover tobacco buys, as well as working with a regional emergency medical services staffing agency. These work-based learning opportunities are rapidly expanding, with several state and local law enforcement internships on the horizon.

In short, these students are ideal future law enforcement candidates.

Accomplishments

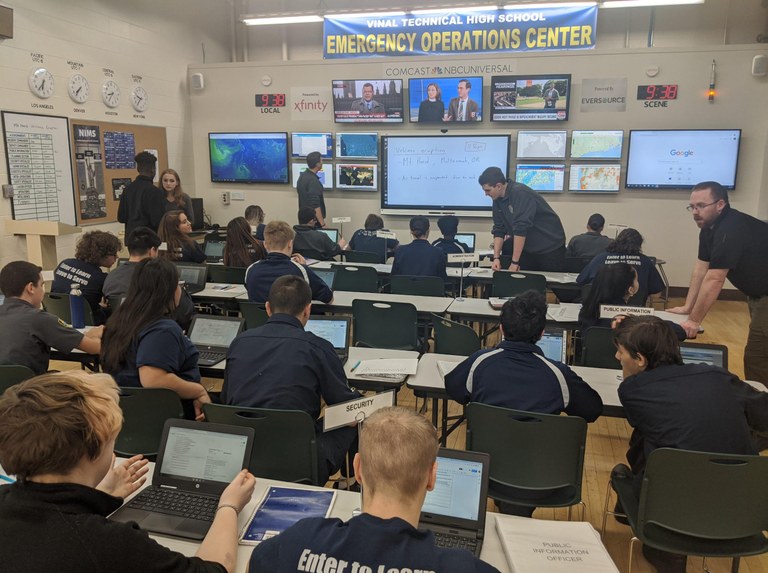

The CJPS program partnered with two large corporations that generously helped build a $40,000 emergency operations center for the students to take their skills and acquired knowledge to a new level. Through the center, students are taught collaboration, teamwork, communication, and critical thinking skills that can be applied to their future careers.

Students are not only learning but also doing. They successfully assisted in two national disasters, providing extensive daily information using a 26-page incident action plan, all on proper federal forms, to federal medical teams deployed to California and Wyoming. The students’ work was so impressive that it earned them recognition from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and they plan to continue providing support for all future national disasters.

Recommendations

The most surprising aspect of developing Connecticut’s CJPS program has been how hungry high school students are to learn and make a real difference in their communities, much like what the best law enforcement candidates express to hiring panels. So, why not start recruiting earlier? Even if students in these programs decide to do other things after graduation, they will have a profound appreciation for the trade and become some of the best witnesses, good Samaritans, and even prosecutors. Local, state, and federal agencies can use five simple ways to cultivate these candidates to join their ranks.

“The CJPS [Criminal Justice and Protective Services] program provides high school students with more certifications than most 3- or 4-year officers have earned, while preparing them to be ideal candidates. … ”

1) Find or suggest CJPS programs.

There are a few states that offer programs similar to the CJPS, and in the ones that do not, it is usually because no one has suggested it. Finding these programs or suggesting their development is the first step. Schools want students to be successful. If there is no program nearby, educators can tailor a smaller version to fit their traditional high school model.

When faced with a roadblock, great candidates can be found outside of the area. The CJPS pulls students from dozens of surrounding communities. One of the program’s biggest supporters in terms of training personnel and equipment is a fire department located over an hour away from the school, and students remember that. They want to be a part of that department after graduating.

2) Build relationships.

These technical programs do not require the dedication of a school resource officer. In fact, it is just the opposite. Students want to meet an agency’s training staff, participate in training exercises as actors, use the equipment that is being thrown away, and tour specialized units. They want to feel like they are part of an organization and be able to call on the people they meet when they have class questions.

The CJPS program uses local responders as panel judges for fun class activities, which builds a strong bond using humor and positive feedback. The program has also provided over 40 students at a time for local full-scale exercises, which adds to the training realism for an agency’s personnel while giving students a school day they will never forget.

3) Offer experiences and internships.

Interning and working with an agency lets students know what it will be like working at that department. It lets them build friendships, future references, and valuable skills, all while benefiting the agency.

The FDA’s Youth Inspector program is an excellent example. Under the supervision of an adult compliance officer, part-time youth inspectors get paid to participate in actual field work, posing as customers attempting to buy tobacco as minors to ensure that retailers are abiding by the law. The program operates in all 50 states, and openings can be found periodically.

Explorer programs are an excellent way to court future candidates, but in the absence of such programs, internship opportunities, ride alongs, and shadowing are effective tools. Students feel much more connected when given a meaningful project. Even if a project needs to be reviewed, giving students tasks that are not just busy work and require them to do research gives them the sense of pride everyone seeks in their careers.

“The most surprising aspect ... has been how hungry high school students are to learn and make a real difference in their communities, much like what the best law enforcement candidates express to hiring panels.”

4) Take advantage of the students’ technical prowess.

Current high school students were born no earlier than 2003 — during the digital age — and have not lived in a world without WiFi (1997), Bluetooth headsets (2002), USB flash drives (2000), or smartphones (2003).5 This can be used as an advantage. The CJPS program is continually passing along valuable social media intelligence, such as what apps are becoming popular, how to use them, how they can be abused, and what to look for, to local law enforcement. Why not enlist the help of some local students to find social media profiles of low-level fugitives or help uncover fraudulent operations? They are more mature than most realize, and if given the proper direction, their responsibility will impress.

5) Reward hard work.

Give students a reason to come to one agency over another. The CJPS is working, one by one, on getting local agencies to change their hiring language from requiring an associate’s or bachelor’s degree to either minimally accepting, or at least awarding hiring points for, completion of the CTECS CJPS program. The students worked hard to complete the program and are coming into the workforce with multiple certifications and real-life experience — rewarding their achievements will only make them more interested.

Additional Resources

- Law and Public Safety Education Network, https://lapsen.org/

- Vinal Criminal Justice and Protective Services, https://www.vinalcjps.com

- Career Technical Education, https://careertech.org/cte

- Tobacco Compliance Check Inspections, https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/compliance-enforcement-training/ctp-compliance-enforcement

Mentorship Opportunities

- Youth Preparedness Council, https://www.ready.gov/kids/youth-preparedness-council

- FBI National Academy Associates Youth Leadership Program, https://www.fbinaa.org/FBINAA/Training/Youth_Leadership_Program.aspx

- CyberStart America, https://www.cyberstartamerica.org/

- Skills USA, https://www.skillsusa.org/about/why-career-technical-education/

“Integrating an agency with a high school program such as Connecticut’s is simple, does not have to drain resources, and can be started small.”

Conclusion

Building the best candidates has always been about starting as early as possible. As such, the CTEC CJPS program is ever-expanding to meet the needs of the field to accomplish that goal. From the first time the students handle a CPR mannequin to their experiences running a real emergency operations center, these students are eager and driven to be successful.

Integrating an agency with a high school program such as Connecticut’s is simple, does not have to drain resources, and can be started small. The first step is to locate local programs and reach out. Instructors are always excited to bring in more opportunities for their students and will want to build those relationships regardless of the agency size or resources. In absence of a similar program, departments can offer mentorship or internship opportunities to the local schools, and the students will remember those interactions. Finally, agencies should take advantage of the students’ technical prowess and reward their dedication so they will want to be a part of the organization.

Connecticut will reap the success of the CJPS program as it grows, and, hopefully, other departments can benefit from it as well.

Mr. Cruickshank can be reached at David.Cruickshank@cttech.org.

Endnotes

1 Chris Skinner, “Recruiting with Emotion and Market Positioning,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, July 1, 2010, https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/recruiting-with-emotion-and-market-positioning; and Susan Hilal and James Densley, “The Right Person for the Job: Police Chiefs Discuss the Most Important Commodity in Law Enforcement,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, October 9, 2015, https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/the-right-person-for-the-job-police-chiefs-discuss-the-most-important-commodity-in-law-enforcement.

2 Connecticut General Assembly, Office of Legislative Research Report, Milestones in Connecticut Education: 1912-2012, Carrie Rose, 2012-R-0094, February 28, 2012, https://www.cga.ct.gov/2012/rpt/2012-R-0094.htm.

3 American College of Surgeons, “STOP THE BLEED,” accessed August 3, 2021, https://www.stopthebleed.org.

4 U.S. Department of Homeland Security, National Incident Management System, Federal Emergency Management Agency, (Washington, DC: October 2017), 24-33, https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_nims_doctrine-2017.pdf.

5 Kevin Smith, “10 Game-Changing Pieces of Tech from the 2000s,” Business Insider, August 2, 2012, https://www.businessinsider.com/game-changing-tech-from-the-2000s-2012-8.