Building Resilience to Violent Extremism: One Community’s Perspective

By Stevan M. Weine, M.D., and John G. Horgan, Ph.D.

In August 2011 the White House released a brief document titled “Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States,” which was the United States’ first attempt at a strategy to build community resilience to counter violent extremism.1 Four months later the White House released the more detailed “Strategic Implementation Plan for Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States.”2 These documents describe how the U.S. National Security Strategy’s approach to countering violent extremism (CVE) includes a focus on prevention.

The Strategic Implementation Plan (SIP) recommends several practical steps for prevention through empowering local partners. One recommendation highlights the need to “foster community‐led partnerships and prevention programming through expanding community‐based solutions.”3 Another suggests providing communities with “information and training, access to resources and grants, and connections with the philanthropic and private sectors.”4

However, for all of its recommendations, the SIP does not directly address how adversities linked to structural and environmental factors would impact implementation in communities under threat.5 Somali-Americans in Minneapolis-St. Paul comprise a disadvantaged refugee resettlement community with low parental education and high rates of violence exposure, unemployment, and poverty.6 Prevention efforts in other fields, such as public health, demonstrate that structural and environmental factors can drive unwanted outcomes, and programs that do not take these factors into account likely will fail.7

The challenges faced by Somali-Americans were recognized nationally in 2007 and 2008 when 18 boys and men secretly left their homes to travel to Somalia where they were taken to the Al Shabaab terrorist organization’s training camps. One of these men deployed as one of six suicide bombers who killed more than two dozen people on October 29, 2008, in Hargeisa‐Bosaso, Somalia. To address such problems, the authors strives to help agencies understand some key priorities and challenges for building community resilience to violent extremism based on the findings from a study of Somali-Americans in Minneapolis-St. Paul.8

ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY

Through a government-academic community collaborative effort, researchers used ethnographic methods to study 53 youth, parents, and community service providers in the Somali-American community. They derived an empirical model—Diminishing Opportunities for Violent Extremism (DOVE). The results of this study do not generalize to all Muslim-American or Somali communities. However, studying one community under threat enabled these researchers to examine the assumptions inherent in implementing the national CVE strategy. The study also provided valuable local community perspectives on some key challenges underlying its implementation.

The findings described risk and resilience as properties of the community and its families and showed how they could be modified by community-based and family-focused prevention activities. These results also identified how risk factors combined to create opportunities for entering into violent extremism and how protective resources could stop, delay, or diminish such opportunities.9 The study suggested that efforts to increase resilience should involve collaborative initiatives to enhance protective resources against those possibilities.

Dr. Weine is a professor of psychiatry and director of the International Center on Responses to Catastrophes at the University of Illinois, Chicago, College of Medicine.

Dr. Horgan is a professor of security studies at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell and director of the Center for Terrorism and Security Studies.

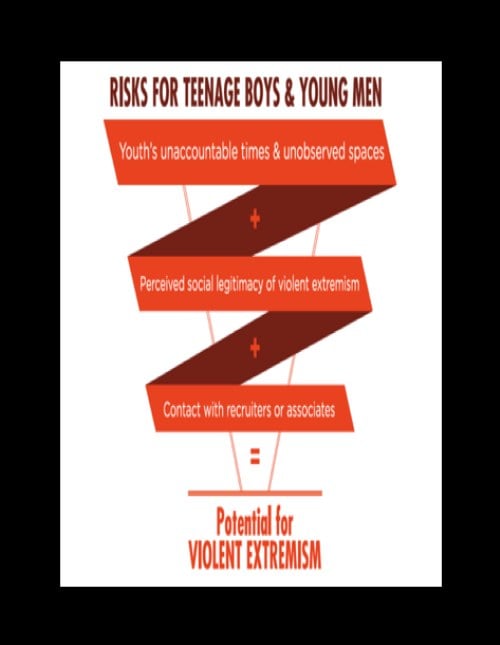

The DOVE model indicates that preventive initiatives should be directed at three risk levels contributing to potential involvement in violent extremism. The goals are to diminish youth’s unaccountable times and unobserved spaces, the perceived social legitimacy of violent extremism, and the potential for contact with terrorist recruiters or associates. At every risk level researchers found protective resources from three partnership groups—youth and family, community, and government.

Figure 1. Risk Levels.

PREVENTION GOALS

Diminishing Unaccountable Times and Unobserved Spaces

There are times when adolescent boys and young men are out of sight and not accountable to their parents or other adults. A community service provider explained, “You get out of school at 3:00 p.m. and you have 4 or 5 hours with nothing to do.” Research findings identified 20 protective resources that could help counter this risk. One resource, awareness of risks and safeguards, was illustrated by a parent who said, “I think the parents should be educated…. They should have meetings about what is happening with the youth and they should talk to the youth. That would help oppose it. Educate the families first and then talk to the youth.”

Table 1. Prevention Aim #1

| Levels | Protective Resources |

| Youth and Family | Awareness of Risks and Safeguards Parental Monitoring and Supervision Family Confidants Family Social Support Family Involvement in Education Access to Services and Helpers Parental and Youth Help Seeking Parental Involvement in Mosques and Religious Education |

| Community | Trusted Accurate Information Sources Increased Activities in Supervised Community Spaces Mentoring of Youth Increased Civilian Liaisons to Law Enforcement Interactions with Community Police Social Entrepreneurship Interfaith Dialogue Social Support Networks |

| Government | Community Policing Support for Parenting and Parent Education Support for After-School Programs and Mentoring Support for Youth and Family Social Services |

Decreasing Perceived Legitimacy

The study revealed that perceptions about the appropriateness and necessity of violent extremist ideology and its actions were common. For example, one youth said, “We were the generation that was going to help Somalia become a better country.” This attitude predisposed some youth to solutions proposed by violent extremists to restore Somalia. One youth spoke of the protective resource of family confidants. “The media sometimes lies. So I’d rather ask my dad or uncle who were there. I ask my dad how the war started.” Strengthening 17 protective resources indicated in table 2 could inhibit the perception of legitimacy.

Table 2. Prevention Aim #2

| Levels | Protective Resources |

| Youth and Family | Focus on Youth’s Future in the United States Parental Support for Youth Socialization Rejecting Tribalism and War Parental Talk with Youth Regarding Threats Youth Civic Engagement Youth Political Dialogue |

| Community | Islamic Education and Imam Network Community Support for Youth Socialization Understanding of Islam as a Peaceful Religion Youth Opportunities for Peace Activism Messaging to Challenge Legitimacy of Violent Extremism Youth Civic Engagement Youth Political Dialogue |

| Government | Empowering Critical Voices Support for Youth Community Services Support for Youth Leadership Training Support for Parenting and Parent Education |

Countering the Potential for Contact

Adolescent boys and young men sometimes interacted with recruiters or companions who facilitated their increased engagement with violent extremism. One youth described a lecture in the community. “They’ll say ‘Hey do you love your country? Do you want to do something for your people? They’re dying.’” One protective resource, community messaging, was explained by a service provider. “Somali elders can take a role to educate people. Elders should organize meetings, discuss the consequences of poor communication with our kids, and explain our culture and true religion, so that nobody can take advantage of our youth.” Findings indicated that supporting the 11 protective resources listed in table 3 could help counter the potential for contact with terrorist recruiters and associates.

Table 3. Prevention Aim #3

| Levels | Protective Resources |

| Youth and Family | Parents Informing Law Enforcement Parental Messaging in Community Regarding Youth Protection |

| Community | Cooperation with Law Enforcement Monitoring by Community Members Messaging to Ward Off Recruiters Bloggers and Websites Against Violent Extremism Emergence of Critical Voices in the Community |

| Government | Training for Community Leaders and Providers Support for Community Messaging Community Policing Bloggers and Websites Against Violent Extremism |

PREVENTION PROGRAMS

The DOVE model indicates that building community resilience to violent extremism should involve sustaining, strengthening, or initiating the aforementioned protective resources at each of the three risk levels. This requires cooperation and collaboration among youth and family, community, and government. At every risk level, all partners should strengthen the protective resources they can and work with partners to enhance their capacity to do the same thing.

There are multiple ways for prevention programming to diminish the risk of violent extremism. Four strategies focused on youth and young adults, which were devised from the study of Somali-Americans in Minneapolis, St. Paul, also may apply to other communities.

Supplying Information

Many parents and youth need help recognizing current risks and strategies to mitigate them. Parents need to know how to talk with their children about the dangers of violent extremism. For many, new parenting strategies are necessary, particularly in managing common urban problems. Somali-American community members reported that parents typically do not rely on mainstream media, which they regard as inaccurate, incomplete, and biased against their community. Information and advice for most parents and youth comes from the Somali media or word of mouth. New ideas and knowledge could be disseminated through these sources.

Changing Norms

Community members suggested providing logistical support and training to elders and other critical voices. These initiatives could develop messaging to challenge the desire of young people to return to Somalia to fight. Support and coordination would be essential to ensure that efforts were focused on at-risk youth and young adults, effective, and sustainable. The goal would be to reframe these young people’s passion for helping Somalia into other ways to serve the Somali-American community.

Enhancing Services

Prior to the mobilization of youth to Somalia, community members and academics identified the need for youth services, housing, employment, and reduction of violence.10 Youth and families face obstacles to accessing services and often must fend for themselves. To address these problems, new and expanded services from law enforcement and other community-based providers—mutual assistance associations, schools, and resettlement agencies—are needed. Alleviating pressing problems could reduce the risks for violent radicalization for some youth and improve communitywide perceptions about American society and government.

Providing Service Opportunities

Prevention programming could provide the means for young people to engage in public service. Community members critiqued several small-scale initiatives for insufficient opportunities and lack of sustainability. Somali community advocates have called for an expansion of humanitarian and peace-work opportunities.11 New programs for diasporic youth create alternatives for channeling their passion for their homeland and people.

PARTNERSHIPS

The SIP states that collaborative partnerships are necessary for building resilience to violent extremism. It calls for sharing sound, meaningful, and timely information; responding to concerns; and supporting community-based solutions.12 The present study highlighted three challenges to implementation through partnerships and ways to approach them.

Establishing Trust-Building Partnerships

One hindrance to collaborative partnerships is community mistrust of law enforcement and government. This is a significant obstacle for Somali-Americans because as refugees they fled from a totalitarian state where government officials, especially law enforcement, were perceived as dangerous and threatening.13

One community leader, referring to work with at-risk youth, indicated, “The challenge is determining how to win their trust.” Some community leaders regard partnering with law enforcement and government as a liability without clear benefits. Establishing collaborative partnerships involves building trust and emphasizing the benefits of collaboration.

Enhancing Organizations’ Capacities

Another challenge is addressing structural and environmental factors, which requires not only law enforcement but organizations and individuals involved in immigration, education, health, employment, and housing. Implementation should incorporate several partners—faith-based organizations, mutual assistance associations, social service agencies, schools, health care providers, mental health organizations, and the media.

An important question is whether these organizations are being asked to do what they typically do—provide support to refugee families—or something new, such as offer security-focused education and support. If the former is true, nobody should expect different results; if the latter, this requires new knowledge, skills, structures, leadership, and relationships.

Extending the Reach of Prevention

Another implementation challenge is that at-risk individuals often are not linked with community-based organizations. Current knowledge from other fields with successful prevention programs suggests that efforts should directly reach those who are at high-risk for violent extremism.14 For that reason, some initiatives in other disciplines have attempted indirect strategies—for example, engaging high-risk populations via informal social networks or communitywide efforts to change cultural and social norms.15

Implementation plans for broader or multilevel efforts may be appropriate but should avoid an “everything approach” toward prevention, which could be costly and defy feasibility.16 Organizations conducting prevention programming must reach out to high-risk youth and young adults or partner with associations already in contact with them.

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

Building community resilience to violent extremism involves promoting public safety—the prevention of events that present a risk from significant danger, injury, harm, or damage, such as crimes or disasters. Therefore, CVE could be approached like other public safety activities that call for community participation, such as child protection.17 However, the nature of that involvement is distinct because of ethnic and religious identity, citizenship, and national allegiance concerns. Three themes emerged from the research findings.

Transforming Values and Practices

Building community resilience to violent extremism is ambitious. The goal is to impact social and psychological processes that will reduce risks and strengthen community and family protection. This means making changes to mitigate not only terrorist threats but also crime, drugs, delinquency, and human trafficking, which are co-occurring problems in many Somali-American communities.

Enhancing Cooperation

Law enforcement organizations alone cannot build community resilience to violent extremism. The goals are to promote security by diminishing radicalization, mobilization, and recruitment via prosocial community involvement of those who may be difficult to engage. Similar to community policing, building community resilience to violent extremism requires a proactive, multilevel, intensive, collaborative, and ongoing effort.18 It should engage local communities and help them approach and solve problems.

Evolving Political Expression

The public safety issues involved with protecting youth and families cannot be disentangled from the political issue of who is a friend or enemy to a community.19 Establishing the social legitimacy of violent extremism depends on making a convincing political argument, which Al Shabaab and its affiliates did. Thus, challenging that legitimacy requires convincing political counterarguments directed toward young people. Building community resilience should involve facilitating efforts for opinion leaders to voice their ideas via community spaces, social media, and other networks.

CONCLUSION

The SIP proposes an approach that focuses on activities with “the greatest potential to prevent violent extremism.”20 For that potential to be realized, law enforcement must forge collaborative partnerships with community-based organizations. Together they must develop and implement effective programs and get youth, family, and community to participate. These programs must have a significant impact on targeted outcomes that diminish risks for violent extremism. The SIP indicates that this is a first-time effort and that over time more will be learned about its effectiveness.21

Presently, little scientific evidence exists for the effectiveness of CVE programs; however, indirect evidence supports the prevention approach based upon studies in other fields such as criminology, public health, and mental health.22 Policymakers and programmers should draw from this evidence to guide new initiatives by sponsoring lesson-sharing forums. Yet, going forward, indirect evidence is not adequate scientific support to establish the value of these initiatives and determine if adjustments and adaptations are needed.

The rationale and acceptance of CVE through building community resilience is likely to be challenged over time. Critics and skeptics may call for proof of the effectiveness of these policies, heightening the urgency to establish monitoring and evaluation tools to demonstrate that SIP-inspired prevention programming works. Presently, the SIP recommends developing indicators for key benchmarks; assessing impact; and examining gaps, areas of limited progress, and resource needs, all of which represent significant challenges.23

The underlying question remains whether policymakers will invest in a scientific approach to building community resilience to violent extremism like they have for other social ills such as HIV transmission and juvenile violence. Such an investment could ensure public confidence that the necessary learning will take place.

Dr. Weine may be contacted at smweine@uic.edu, and Dr. Horgan may be contacted at John_Horgan@uml.edu.

This project was funded through START by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Science and Technology Directorate, Human Factors/Behavioral Sciences Systems Division(now the Resilient Systems Division).

Endnotes

1 The White House, “Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States, 2011,” http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/empowering_local_partners.pdf (accessed November 18, 2013).

2 The White House, “Strategic Implementation Plan for Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States, 2011,” http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/sip-final.pdf (accessed November 18, 2013).

3 The White House, “Strategic Implementation Plan,” 10.

4 The White House, “Strategic Implementation Plan,” 10.

5 K.M. Blankenship, S.R. Friedman, S. Dworkin, and J.E. Mantell, “Structural Interventions: Concepts, Challenges, and Opportunities for Research,” Journal of Urban Health 83, no. 1 (January 2006): 59-72, http://link.springer.com/article/10-1007/511524-005-9007-4# (accessed December 16, 2013).

6 Helen Silvis, “Somali-American Council of Oregon Seeks to Unite Frightened Community,” The Skanner News, February 27, 2013, http://www.thescanner.us/article/Somali-American-Council-Oregon-Seeks-to-Unite-Frightened-Communities/2013-02-27 (accessed December 16, 2013).

7 Kathleen E. Etz, Elizabeth B. Robertson, and Rebecca S. Ashery, “Drug Abuse Prevention Through Family-Based Interventions: Future Research,” in Drug Abuse Prevention Through Family Interventions, ed. Rebecca Singer Ashery, Elizabeth B. Robertson, and Karol Linda Kumpfer (Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1998), http://archives.drugabuse.gov/pdf/monographs/monograph177/001-011-Etz.pdf (accessed December 16. 2013).

8 Stevan Weine and Ahmed Osman, “Building Resilience to Violent Extremism Among Somali‐Americans in Minneapolis‐St. Paul,” National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), http://www.start.umd.edu/start/publications/ Weine_BuildingResiliencetoViolentExtremism_SomaliAmericans.pdf (accessed November 18, 2013).

9 Weine and Osman, “Building Resilience.”

10 Rose French and Kevin Diaz, “Mary Jo Copeland Receives Presidential Medal,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN), February 15, 2013, http://www.startribune.com/local/minneapolis/ 191405671.html (accessed December 16, 2013).

11 Cindy Horst, International Peace Research Institute (Oslo, Norway), “Connected Lives: Somalis in Minneapolis, Family Responsibilities and the Migration Dreams of Relatives,” (July 2006), The UN Refugee Agency, http://www.unhcr.org/44b7b6912.html (accessed January 6, 2014).

12 The White House, “Strategic Implementation Plan,” 7.

13 Bill Meyer, “Somali Militants Use Many Tactics to Woo Young Americans to Jihad,” Cleveland.com, August 25, 2009, http://www.cleveland.com/nation/index.ssf/2009/08/ somali_militants_use_many_tact.html (accessed November 21, 2013); Andrea Elliott, “A Call to Jihad Answered in American,” New York Times, July 11, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/ 12/us/12somalis.html?pagewanted=all (accessed November 21, 2013); and Andrea Elliott, “Charges Detail Road to Terror for 20 in U.S.,” New York Times, November 23, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/24/us/24terror.html (accessed November 21, 2013).

14 Alice E. Hunt, Kristin M. Lord, John A. Nagl, and Seth D. Rosen, Beyond Bullets: Strategies for Countering Violent Extremism (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, 2009), http://www.cnas.org/files/documents/publications/LordNaglRosen_Beyond%20Bullets%20Edited%20Volume_June09_0.pdf (accessed November 21, 2013).

15 Mary Ellen O’Connell, Thomas Boat, and Kenneth E. Warner, eds. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009), http://www.whyy.org/news/ sci20090302mentalprepub.pdf (accessed December 16, 2013); and Carl A. Latkin, Valerie Forman, Amy Knowlton, and Susan Sherman, “Norms, Social Networks, and HIV-related Risk Behaviors Among Urban Disadvantaged Drug Users,” Social Science and Medicine 56, no. 3 (February 2003): 465-476, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s0277953602000473 (accessed December 16, 2013).

16 Andrew Zolli and Ann Marie Healy, Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back (New York, NY: Free Press, 2012).

17 Kamaldeep S. Bhui, Madelyn H. Hicks, Myron Lashley, and Edgar Jones, “A Public Health Approach to Understanding and Preventing Violent Radicalization,” BMC Medicine 10, no. 16 (February 2012): 1-8, http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/10/16 (accessed December 17, 2013).

18 Michael P. Downing, “Policing Terrorism in the United States: The Los Angeles Police Department's Convergence Strategy,” The Police Chief, February 2, 2009, http://www.policechiefmagazine.org/magazine/index.cfm?fuseaction=display_arch&article_id=1729&issue_id=22009 (accessed November 21, 2013).

19 Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political trans. George Schwab (1932; repr., Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996).

20 The White House, “Strategic Implementation Plan,” 6.

21 The White House, “Strategic Implementation Plan,” 6.

22 Stevan Weine and Saif Siddiqui, “Family Determinants of Minority Mental Health and Wellness,” in Determinants of Minority Mental Health and Wellness, eds. Sana Loue and Martha Sajatovic (New York, NY: Springer, 2009), 221-254.

23 The White House, “Strategic Implementation Plan,” 7.