Crowd Management

Adopting a New Paradigm

By Mike Masterson

Managing crowds is one of the most important tasks police perform. Whether or not members of the public agree with this practice, they often judge how well law enforcement officers achieve this—if it is done fairly and effectively. Of course, officers should treat everyone with respect and courtesy without regard to race, gender, national origin, political beliefs, religious practice, sexual orientation, or economic status. Although perhaps daunting, the primary function of police is relational, whether they respond to a domestic dispute, investigate a crime, enforce a traffic regulation, or handle a crowd. Once officers understand this, they will find it easier to determine what to do and how to do it.1

Lessons Learned

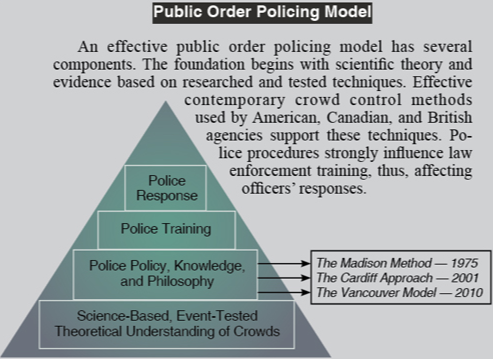

Studied by law enforcement for at least 40 years, crowd control is important due to the dangers posed by unruly gatherings. To this end, it proves fair to ask whether police leaders do all they can to share lessons learned and incorporate best practices into crowd management philosophy, training, and tactics.

As a young police officer in Madison, Wisconsin, in the 1970s, the author experienced the Vietnam War’s aftermath at home and the eruptions of student unrest. A state capital and home to a major university, Madison at times is a hotbed for protests. From antiapartheid demonstrations and dismantling of shantytowns on capitol property to an annual alcohol-laden Halloween festival, the author, along with fellow officers, monitored and managed partiers and protesters for over four decades. With groups ranging from 6 church members to 250,000 people celebrating in a city park, Madison police successfully balanced rights to assembly and free speech with citizen and officer safety.

The author benefited from those lessons on crowd management when becoming chief of the Boise, Idaho, Police Department in 2005. The city subsequently hosted the National Governors’ Conference and the 2009 Special Olympics World Winter Games. Boise police officers manage a wide variety of protests, parades, and demonstrations on issues, such as immigration, human rights, and most recently, a death penalty execution and Occupy Boise.

A police chief’s involvement and direction prove critical to officers’ ability to successfully manage emotional, potentially volatile crowds. The message received from top-level management greatly influences the behavior and mind-set of frontline officers. Shaping these attitudes begins with a solid understanding that police work involves building relationships with members of the public whom officers are sworn to serve and protect.

British Influence

The International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) have an increasing amount of information available on best practices in crowd management. PERF’s recent publication Managing Major Events: Best Practices from the Field contains insight offered by law enforcement leaders from the United States and Canada on what has worked for them.2 This report includes the Vancouver, British Columbia, Police Department’s new policy on tolerance and restraint when dealing with crowds. Police leadership in Vancouver recognized the success of British crowd control policies, sent their senior executives overseas to study the model, and brought back trainers to assist officers with implementing this new style of crowd control during the 2010 Winter Olympics.

Chief Masterson heads the Boise, Idaho, Police Department.

With British input, Vancouver police developed a meet-and-greet strategy. Instead of using riot police in menacing outfits, police officers in standard uniforms engaged the crowd. They shook hands, asked people how they were doing, and told them that officers were there to keep them safe. This created a psychological bond with the group that paid dividends. It becomes more difficult for people to fight the police after being friendly with individual officers.3

British research on policing crowds confirms the strategic need for proactive relationship building by police. In the 1980s, a professor at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland published early findings on how law enforcement tactics shape crowd identity and behavior.4

Later, a doctor at the University of Liverpool published research on hooliganism—rowdy, violent, or destructive behavior—at British soccer games. Named after fans of a soccer club involved in two riots with South Wales Police in 2001 and 2002, the Cardiff Approach is based on two leading theories of crime reduction—the Elaborated Social Identity Model (ESIM), the leading scientific theory of crowd psychology, and the Procedural Justice Theory (PSJ).

The ESIM maintains that crowd violence escalates if people think police officers treat them unfairly. PSJ proposes that group members comply with the law when they perceive that officers act with justice and legitimacy.5 When a crowd becomes unruly and individuals perceive unfair treatment by law enforcement officers, violence can escalate, and a riot can erupt. Recent research finds support for both perspectives and concludes that when police officers act with legitimacy, disorder becomes less likely because citizens will trust and support law enforcement efforts and behave appropriately.6

The Madison Method

Modern research supports a philosophy of public order policing from the 1970s referred to as The Madison Method of Handling People in Crowds and Demonstrations.7 This approach begins with defining the mission and safeguarding the fundamental rights of people to gather and speak out legally. The philosophy should reflect the agency’s core values in viewing citizens as customers. This focus is not situational; it cannot be turned on and off depending on the crisis.

Law enforcement agencies facilitate and protect the public’s right to free speech and assembly. When officers realize they are at a protest to ensure these rights, they direct their responses accordingly, from planning to implementing the plan. Officers must have a well-defined mission that encourages the peaceful gathering of people and uses planning, open communication, negotiation, and leadership to accomplish this goal.

Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) commanders achieved success in planning and communicating their agency’s mission during an Occupy Los Angeles gathering. Throughout the event, officers’ objective was to facilitate the peaceful removal of all people and their belongings from the city hall park area. Participants received a reasonable amount of time to leave, after which officers issued a dispersal order. Anyone refusing to exit the park faced arrest.8

Officers should begin with constructive engagement, dialogue, and a soft approach. British law enforcement agencies call this the “softly-softly approach.” Law enforcement personnel mingle and relate to the crowd using low-key procedures based on participants’ behavior, rather than their reputation or officers’ preconceived notions of their intent.

Police and demonstration organizers should coordinate prior to an event. This re-enforces law enforcement’s role as facilitator, rather than confronter. Maintaining dialogue throughout the event helps minimize conflict. Of course, dialogue involves two-way conversation—sometimes this means listening to unpopular opinions and suggestions. There is only one crowd; however, individuals comprise that mass. If the event is peaceful, officers should remain approachable to, for instance, give the location of the nearest ATM, provide the phone number for a taxi, or supply directions to a parking lot.

Officers must avoid donning their hard gear as a first step. They should remember lessons learned from the 1960s civil rights movement and Vietnam War protests. Police should not rely solely on their equipment and tools.9 Experience shows that when used as a primary tactical option in public order policing, dialogue is invaluable. Law enforcement officers must defuse confrontations to ensure strong ties with the community. If they fail, rather than stronger community goodwill, the effect will be less civility and the erosion of constitutional rights.10

Negotiation and Education

“Officers should begin with constructive engagement, dialogue, and a soft approach.”

Officers must negotiate, educate, and maintain continual dialogue with organizers and crowd members. Police personnel initially must state that they defend the public’s right to demonstrate, but cannot allow the crowd to hurt others or destroy property. Whether officers support the crowd’s position or if the group holds an unpopular view, law enforcement agencies must remain neutral and prevent physical injuries or property destruction. If arrests become necessary, police officers must respect individuals and avert harm to anyone in custody. Officers must convey that they expect cooperation in return.

Recently, an elected leader in Boise recognized the need for officers to address crowd management questions. It became apparent that some demonstrators misinterpreted law enforcement agencies’ approach. While police engaged in reasonable, steady conversation, the public sometimes saw this as uncaring, which indicated the importance of educating demonstrators early. In Vancouver, officers quickly relayed to Winter Olympics fans the strategy to keep everyone safe.

Protection and Professionalism

Protecting officers who work with a crowd is important. The Stockholm, Sweden, Police Department uses highly visible and identifiable “dialogue police,” while British law enforcement agencies use “communication police.” The Boise Police Department, maintains a tactical unit with full protective equipment on standby in an out-of-sight location near the demonstration. The unit serves as an emergency response to protect officers and the public from harm. Its mission is to safeguard people first and property second. Deploying the emergency response team is a last alternative when soft crowd control tactics prove ineffective.

Law enforcement agencies can show leadership in preparation and training for events by using specially qualified police officers. The best officers to use in crowd control situations are those specifically selected and trained who have the personality to use a soft approach under difficult circumstances. Self-control proves essential.

Not all police officers can manage multitudes effectively. Crowd control offers a rare opportunity for agencies to cultivate a positive public image. When officers operate as a team, the public observes confidence and professionalism far above any uniformed presence.

“British research on policing crowds confirms the strategic need for proactive relationship building by police.”

Accountability and Visibility

While restraining from the employment of force is important, its use may become necessary at large gatherings, especially those born out of passion. Officers working at large events must realize that someone watches and records all arrests. Police officers with up-to-date training in making team arrests ensure efficient apprehensions.

Avoiding the use of outside agencies can be wise. Officers from other locations may differ in philosophy, training, or ability to work together during a conspicuous event. External resources could lack soft crowd management experience or community knowledge. It proves important to local agency leaders that officers take personal responsibility for crowd management in their city.

Occasionally, outside help proves necessary. A recent event in Boise required the participation of five large agencies consisting of state, county, and city forces. The effort was well-planned and coordinated. Success came from all stakeholders’ early planning and clear understanding of the mission.

Avoiding anonymity and promoting accountability are essential. By ensuring police officers assigned to crowd control are identifiable, with names and badge numbers clearly visible, agencies prevent their officers from becoming anonymous agents. Obscurity or depersonalization of officers encourages negative crowd behavior and leads to unaccountable actions.

Agencies should videotape events. Segments recorded by participants, bystanders, and media are useful; however, when departments record their own documentation, they ensure its value for case review, accountability, and context. The University of California, Berkeley, Police Department has such a practice. Normally, it videotapes all demonstrations or crowd situations to ensure complete records of the event. During periods in which violations, police actions, or other significant activities occur, the agency employs at least two video cameras.11 To safeguard the First Amendment and privacy rights of those participating in the event, agencies should adopt a policy governing retention and destruction of these tapes.

During high-profile or large demonstrations, police command officers must remain on the scene, visible, interactive, and willing to take charge. This provides an excellent opportunity to assess the mood of the crowd and reinforce the agency’s outlook and crowd management tactics.

Communication and Preparation

With 24-hour news, cell phone cameras, Facebook, Twitter, and hundreds of other social media connections, it becomes important to prevent potentially dangerous rumors from appearing as facts. Because of erroneous witness statements and other misleading or false information, justifiable use of force has triggered riots. Law enforcement agencies play a major role in responsibly reporting accurate information quickly and continually for the benefit of officers, the public, and the media. Although officers are not responsible for inaccurate reporting, developing a proactive, engaged media plan is important. Social media serves as an excellent way to directly communicate department messages and obtain information on events.

“Participants perceive the legitimacy of police actions based on how officers interact with the crowd throughout an event.”

Law enforcement agencies must have a plan to de-escalate conflict situations. If an arrest becomes necessary, the individual taken into custody should be one who threatens the peace of the event. Sometimes, officers disperse a crowd to preserve harmony and prevent injuries and property damage. Police officers with specialized skills and equipment do this best. Law enforcement agencies must prepare for circumstances that suddenly can turn a crowd confrontational.

At any large demonstration, law enforcement officers primarily serve as peacekeepers facilitating lawful intentions and expressions. Participants perceive the legitimacy of police actions based on how officers interact with the crowd throughout an event. Communicating expectations, negotiating continually, and emphasizing the goal of safety are vital. Officers should not confuse the actions of a few with those of the group. Law enforcement personnel must remain firm, fair, and professional.

Conclusion

Commonplace instant, mass, and social media provide an opportunity to highlight and improve the public’s view of law enforcement legitimacy. Using communication and best practices in crowd management, officers reinforce their position as peacekeepers. Police, the most visible form of government, must continue to ensure that the First Amendment rights of the public they serve are protected and guaranteed.

“Law enforcement agencies play a major role in responsibly reporting accurate information quickly and continually for the benefit of police, the public, and the media.”

Endnotes

1 D. Couper, Arrested Development: One Man’s Lifelong Mission to Improve Our Nation’s Police (Madison, WI: Dog Ear Publishing, 2012).

2 D. LePard, Managing Major Events: Best Practices from the Field (Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum, 2011).

3 LePard, Managing Major Events.

4 S.D. Reicher, “The St. Paul’s Riot: An Explanation of the Limits of Crowd Action in Terms of a Social Identity Model,” European Journal of Social Psychology 14 (1984): 1-21; and S.D. Reicher, “Crowd Behavior as Social Action,” in J.C. Turner, M.A. Hogg, P.J. Oakes, S.D. Reicher, and M.S. Wetherell, Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self Categorisation Theory (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1987).

5 C. Stott, “Study Identifies Best Approach to Policing Football Matches,” University of Liverpool, UK, University News, October 20, 2011, https://news.liv.ac.uk/2011/10/20study-identifies-best-approach-to-policing-football-matches/?utm_source=University+News&utm_medium= email&utm_term=26-10—11&utm_campaign=fortnightly+update (accessed April 19, 2012).

6 C. Stott, “Crowd Psychology and Public Order Policing: An Overview of Scientific Theory and Evidence” (presented to the HMIC Policing of Public Protest Review Team, University of Liverpool, UK, School of Psychology, September 2009).

7 The Madison Method of handling people in crowds and demonstrations was created by Chief David Couper, Madison, WI, Police Department, and staff in the 1970s.

8 U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Incident Management System, Incident Command System (ICS) Form 202, National Commander’s Intent, Occupy Los Angeles, November 29-30, 2011.

9 L. Reiter, “Occupy and Beyond: Practical Steps for Reasonable Police Crowd Control,” Legal and Liability Risk Management Institute (LLRMI), http://www.llrmi.com/articles/legal_update/2011_ crowd_control.shtml (accessed December 13, 2011).

10 A. Baker, “When the Police Go Military,” The New York Times, December 3, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/04/sunday-review/have-american-police-become-militarized.html?_r=1&sq =When%20the%20Police%20Go%20Military&st=cse (accessed June 19, 2012).

11 University of California, Berkeley, Police Department, “Crowd Management Policy,” http://administration.berkeley.edu/prb.PRBCrowdPolicy.pdf (accessed December 12, 2011).