Futures Orientation in Police Decision-Making Practices

The Promise of a Modified Canadian Model

By Michael Buerger, Ph.D., and John Jarvis, Ph.D.

Law enforcement officers are the guardians of the past. Whether out of personal proclivity or as a result of being immersed in the police subculture, their cognitive maps of American culture are flash frozen, an instant in time that encompasses a mythical past. They enforce laws created by legislatures who hold similar visions. At best, those laws reflect a past set of social circumstances and expectations. At worst, they embody a knee-jerk reaction to a crisis du jour long since subsided.

The inherent instability of a chief executive’s position means that a futures orientation cannot be vested in a single person. Although individual leadership is important, the entire law enforcement agency must be infused with a futures orientation. As a guide, the experience of community policing indicates that the most successful approach may be a covert one. Massive publicity that spoke to public concerns without addressing those of the officers often accompanied attempts to establish community policing. The result was raised expectations in one constituency and resistance in others.1 To avoid a repeat of that phenomenon, the first steps toward creating a futures orientation need to be practical, not exhortational.

In this case, being practical means recognizing both the possibilities and the limits of what can be done with police resources. Also, being practical requires developing more than just a conceptual vocabulary that describes the outcomes but, rather, defines intermediate action steps—both processes and results—in language meaningful to the officers who will make these happen.

Broadly speaking, the desired effect is not all that different from the changes sought by the community-policing movement. The task involves changing the police mind-set from that of a fraternity of protectors operating outside the community to one of a network of community-building agents integrated into the criminal justice system.

Leaders must develop a means to break out of the confinement of the immediate and instill a capacity for both recognizing and consciously seeking the small trends of change occurring within their areas. Effective officers always have done this as part of the creation of cognitive maps they call “street sense”; some have specialized in narrow interests, such as burglars and robbers, while others have developed a broader vision. But, these cognitive maps traditionally have resided in the individual. Law enforcement agencies rarely have developed the means to tap into the collective understanding of patrol officers and detectives, resulting in the fragmentation of institutional memory.2

The organizational response generally has been to invest the analytical power in special units, crime analysis, or crime mapping. Although they need not be, these functions tend to be centralized with command level officers as the primary recipients of the work. Individual officers or units can request specific analyses to supplement local investigations or problem-solving efforts. Moreover, some departments encourage officers to engage in their own crime mapping and crime analysis to augment their cognitive maps of their assigned, or beat, areas.

The difficulty in centralized functions of this nature is that they can process only that data routinely archived by the agency, including traditional crime reports and, perhaps, 911 data. Most other information remains ephemeral, resident in the memories of individual officers and small units but not accessible beyond the precinct boundaries. It also is vulnerable to absence (e.g., sick days, vacations, court attendance, and training assignments) and extinguished by transfer or retirement except in the rarest of circumstances. Yet, it is this information—not data, but information—that holds the greatest promise for developing anticipatory policing: that which positions itself to shape the immediate future, rather than to react to it.

Innovation fatigue is a real obstacle to creating change in law enforcement organizations. Rather than introduce a new term, such as anticipatory policing, it would be better to work within the existing law enforcement vocabulary. Problem-oriented or problem-solving policing is the most intuitive to officers at the line level and provides a logical framework for blending a futures approach with a familiar and reasonable accepted conceptual framework. As an example, the authors explore a Canadian approach that offers an alternative to the SARA (scanning, analyzing, responding, and assessment) model that gave the law enforcement world a foundation it could use at the line level of policing.3

THE MODEL

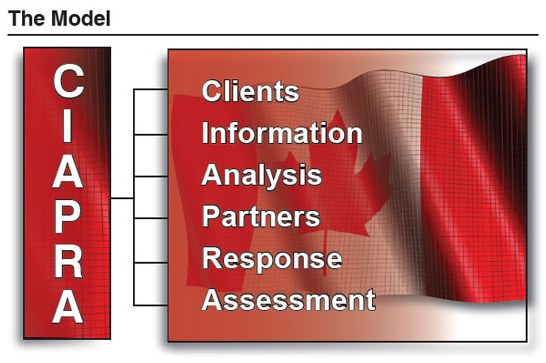

Clients, analysis, partners, response, and assessment make up CAPRA, which holds some promise for infusing futures thinking into policing. With a slight modification of this Canadian perspective to include information, the new acronym CIAPRA represents a second-generation model for problem solving. Such an approach lends itself well to a futures orientation on a small scale, a foundation upon which to build subsequent layers as an officer’s career progresses.

The additional element of information transforms the process from simple problem analysis to baseline intelligence gathering. Requiring officers to identify clients of a particular action moves them beyond the simple tactical view. Similarly, the partners element broadens the perspective of responsibility and capacity. It takes the solution out of the exclusive domain of the police and complicates the process of crafting one at the same time. Adding information to this mix should nudge the effort even further, as databases and repositories of knowledge exist outside the small core of those actors most affected by the problem. Pushing officers beyond the familiar channels of law enforcement thinking will lead to a new awareness of the depths of community resources and the multiple intervention tactics that might be brought to bear upon a problem.

Four critical elements of the CIAPRA model can be expanded. First, clients would include stakeholders who have a positive or negative influence and those possibly disenfranchised, such as targets of police action.4 Second, information needed would cover two primary questions: Where to obtain it? and How to develop it if not readily accessible? Third, analysis, at least initially, would involve the driving forces behind the problem, guardianship issues, possible points of intervention, impact of such intervention (e.g., changes in recent times and trajectory of these), unintended consequences, means of mitigating them, and realistic expected outcomes in light of the intervention and its consequences and mitigation. And, finally, partners would include resources and limitations, as well as motivations and inhibitors.

Implementing Methods

CIAPRA assessments must be built into the regular calendar and stress the officer’s role as the center of an information-gathering network. While quarterly assays are useful, officers should attend to the process in real time, adding observations about changes as they are made. The first round can identify the main players in the officers’ beats and include legitimate citizens and knowledgeable informants on the fringe of the criminal element.

Shift supervisors should emphasize and facilitate ongoing interaction among officers working the same beat area in different time frames. For example, the main players likely will have some variation by time of day, and the officers’ own observations certainly will prove diverse. The process of comparing information will build a more comprehensive understanding of the beat for all officers, regardless of whether they work rotating assignments or steady shifts.

Agencies will need to develop a metric for assessing officers’ work. They must discover when officers are:

- doing a good job;

- just providing lip service;

- adopting a “this too shall pass” attitude; or

- attempting to meet the new demands but encountering difficulties through a lack of skills or an intuitive understanding of the concepts.

Supervisors will know their own people well enough to make these distinctions, assuming the supervisors themselves are on board with the program. In the initial stages, upper-level command staff may need to encourage supervisors, as well as line officers, to give the process a fair hearing.

Active or passive resistance should be relatively easy to detect as the quality of information developed will be inferior to that done by enthusiastic and willing participants. The task of distinguishing between resistance and unskilled but goodfaith attempts at compliance will be more difficult.

The first few training endeavors cannot be expected to produce uniformly successful results; each round of CIAPRA assessments should be considered as an iterative learning experience, further refining the process. CIAPRA can be built into recruit training or agency orientation, but retraining or reorienting serving officers may prove difficult. It will be necessary to develop a new training regimen to assist those who seem to be trying to do a good job but not succeeding. In short, merely setting up the scheme will not be sufficient. Instead, agencies must build in a structure that makes visible use of the officers’ efforts—an intelligence bank.

How supervisors elect to manage the new CIAPRA requirements probably will vary by personality. For instance, some may mandate individual assessments and nothing more. Others may elect to make CIAPRA a group exercise. And, some supervisors may coordinate their squad’s efforts with those of other personnel who cover the same area on different shifts or days.

“Leaders must develop a means to break out of the confinement of the immediate and instill a capacity for both recognizing and consciously seeking the small trends of change...”

The Future of Policing

The FBI actively explores the future of policing through the Futures Working Group (FWG), a partnership between the agency and the Society of Police Futurists International (http://www.policefuturists.org). The mission of the FWG is to promote innovation through the pursuit of scholarly research in the area of police futures to ethically maximize the effectiveness of local, state, federal, and international law enforcement bodies as they strive to maintain peace and security in the 21st century. Members have completed projects on such topics as the use of augmented-reality technology, neighborhood-driven policing, homeland security, policing mass casualty events, and the future of policing. As part of the FWG, the Futurists in Residence program, operational since 2004 and housed within the Behavioral Science Unit of the FBI Academy, affords researchers and practitioners an opportunity to conduct original research.

Developing Applications

Using the information developed productively at the beat and precinct level will pose the greater challenge. CIAPRA as a training guide or a problem-solving template is task focused and finite. In other words, the exercise has an end. As an intelligence-gathering tool or a futures perspective, it is open-ended and subject to constant revision, which goes against the grain of the operational expectations of incident-based policing.

The first round will establish a baseline, but, without follow-up, it simply will be an exercise without utility. The organizational challenge will be to maintain consistency, to repeat the process on a quarterly basis, and to have all officers participate. It also will be an agency responsibility to put the information developed to some visible use.

Sharing Information

Quarterly CIAPRA assessments at the beat level will not be uniform nor lend themselves to traditional computer databases. Much of the beat-level interpretations will be intuitive, nonlinear, and narrative. Making links between reports and across time will be a human endeavor, not a computerized one. Each collection of CIAPRA reports will vary according to the observations made by the officers and their individual writing styles. Agencies can preserve the raw material as a text file or a bound volume, but may find it more useful to invest in text-analysis programs for distilling what inevitably will become huge libraries over time.

In the worst-case scenario (where no useful archiving and retrieval process is developed), a residual, if unstructured, archive still will reside in the human memory of the officers. The greater the amount of purposive interaction and sharing, the greater the probability that the information will be retrieved when the need arises.

CONCLUSION

CIAPRA is not the only model for developing a futures orientation throughout all levels of law enforcement agencies. It does have the advantage of tapping into elements of the police culture that are in place. To be successful, however, it will need to be properly managed, not only at the onset but consistently into the future.

Dr. Buerger, a former police officer, is an associate professor of criminal justice at Bowling Green State University in Ohio and a member of the Futures Working Group.

Dr. Jarvis serves in the FBI Academy’s Behavioral Science Unit and heads the Futures Working Group.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Bernard H. Levin and Richard W. Myers, “A Proposal for an Enlarged Range of Policing: Neighborhood-Driven Policing (NDP),” in Neighborhood- Driven Policing Proceedings of the Futures Working Group, ed. Carl Jensen III and Bernard H. Levin (January 2005), 4-9, http://futuresworkinggroup.cos.ucf.edu/publications/ Vol1-NDP-FWG.pdf (accessed August 10, 2009).

2 Lawrence Sherman, Evidence-Based Policing (Washington, D.C.: Police Foundation, 1998), 5.

3 John Eck and William Spelman, Problem Solving: Problem-Oriented Policing in Newport News (Washington, D.C.: Police Executive Research Forum, 1987).

4 Society as a whole (a given, as in “everything we do is for the community”) as an answer alone is so bland and attenuated as to be useless and, therefore, should be discouraged by supervisory review.