Intelligence-Led Policing in a Fusion Center

By David Lambert, Ph.D.

Much writing and discussion have focused on fusion centers as a key element of a homeland security strategy within policing. These centers have proponents in the homeland security and public safety policy-making structures, as well as critics from civil liberties groups and privacy advocates. A great deal of misperception exists on all sides of the issue regarding the role of fusion centers and intelligence gathering within policing in general.

The concepts of fusion centers, data fusion, and the associated philosophy of intelligence- led policing are abstract terms often misinterpreted and poorly articulated both in and out of law enforcement. While police departments traditionally have had an intelligence- and information-sharing function, the term fusion may be new to some in the profession.1 Similarly, intelligence-led policing, which has many similarities to community and problemoriented policing, might prove relatively unfamiliar to some officers.2 As a result, the incorporation of fusion centers and intelligence-led policing principles into routine law enforcement functions has been a slow and uneven process. However, doing so can make police agencies more effective.

DEFINITIONS

Data fusion is “the exchange of information from different sources—including law enforcement, public safety, and the private sector—and, with analysis, can result in meaningful and actionable intelligence and information” that can inform both policy and tactical deployment of resources.3 Building upon classic problemsolving processes, such as the scanning, analysis, response, and assessment (SARA) model, data fusion capitalizes on a wide array of available data to examine issues ranging from terrorism to traditional street crime. Through data fusion, personnel turn information into knowledge by collecting, processing, analyzing, and disseminating intelligence based upon end users’ needs.

A fusion center is a “collaborative effort of two or more agencies that provide resources, expertise, and information to the center with the goal of maximizing their ability to detect, prevent, investigate, and respond to criminal and terrorist activity.”4 Fusion centers can identify potential threats through data analysis and enhance investigations through analytical support (e.g., flow charting and geographic analysis).

Sergeant Lambert serves in the Massachusetts State Police Commonwealth Fusion Center.

Finally, intelligence-led policing (ILP) refers to a “collaborative law enforcement approach combining problem-solving policing, information sharing, and police accountability, with enhanced intelligence operations.”5 ILP can guide operational policing activities toward high-frequency offenders, locations, or crimes to impact resource allocation decisions.

ROLE OF FUSION CENTERS

Fusion centers allow for the exchange of information and intelligence among law enforcement and public safety agencies at the federal, state, and local levels. A variety of indicators, such as gang behavior, weapons violations, or metals thefts, span jurisdictions. The growth of fusion centers demonstrates that no one police or public safety organization has all of the information it needs to effectively address crime problems. Progressive fusion centers have access to a wide variety of databases, many of which previously were accessible only by individual federal, state, or local law enforcement organizations. Agency participation in multijurisdictional fusion centers diminishes “stovepipes” of information.

Pooling resources, such as analysts and information systems, can maximize limited assets at a time when all agencies face budget cutbacks. Collaboration across organizations blends subject-matter expertise in areas, such as homeland security, violent crime, and drug control. It builds trusted relationships across participating agencies, which encourages additional collaboration. Fusion centers foster a culture of information sharing and break down traditional barriers that stand in the way.6

Combining data from multiple agencies enables policy makers and police managers to see trends and patterns not as apparent when using a single information source. Employing multiple sources helps present a more credible picture of crime and homeland security issues, as when personnel examine field interview data in conjunction with crime incident reports. Personnel often underreport drug or gang offenses, while field interview cards collected by street officers with intimate knowledge of the community may provide a more valid measure of illegal drug use or gang behavior. Using multiple indicators strengthens the information and results in a more coherent and accurate intelligence product.

MASSACHUSETTS EXPERIENCE

Commonwealth Fusion Center

In October 2004, Massachusetts officials opened the Commonwealth Fusion Center (CFC) to focus on terrorism, homeland security, and crime problems across the state. While addressing homeland security challenges is the driving force behind the center, traditional street crimes occur more frequently. The CFC constitutes part of the Massachusetts State Police (MSP), Division of Investigative Services, and employs state troopers and intelligence analysts. Committed staff members from the National Guard, Massachusetts Department of Corrections, FBI, Department of Homeland Security, and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) reflect its multijurisdictional nature. Other agencies participate in the CFC on a part-time or asneeded basis. In addition, the CFC is colocated with the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (NE-HIDTA). This program also incorporates a number of federal, state, and local police agencies to focus on drug control, interdiction, and narcotics intelligence.

Targeting Violent Crime Initiative

As an all-crimes information- sharing and intelligence center, the CFC devotes a significant portion of its analytical resources to examining emerging crime trends. In this regard, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Bureau of Justice Assistance, sponsored the Targeting Violent Crime Initiative, a grant program giving police agencies an incentive to use an ILP approach to address violence. The CFC, responding to a call from state policy makers to examine violent and, specifically, firearms crime throughout the state, proposed to develop a fusion process around weapons offenses.

This effort centers around answering questions about firearms in Massachusetts. First, where do guns used in crimes come from? In other words, do firearms used by criminals— many prohibited from legally owning guns—originate from traffickers bringing them into the state, individuals stealing them from businesses or homes, or other sources? Second, are the lesser-known illegal firearms markets in Springfield, Worcester, and Brockton the same as in Boston? Finally, what are the trends of firearms crime in various parts of the state? Is it on the rise in most large communities or do patterns vary? Which areas have the most stress from firearms crime? Answers to such broad questions can inform policy making.

“Through data fusion, personnel turn information into knowledge by collecting, processing, analyzing, and disseminating intelligence based upon end users’ needs.”

ILP for Firearms Violence

Like many other states, Massachusetts has a number of public safety entities involved in violent crime reduction efforts. To this end, one objective of the CFC’s DOJ-funded Intelligence-Led Policing for Firearms Violence project is to supplement, not duplicate, existing violent crime programs. Through the development of tactical and strategic intelligence products, the fusion center has sought to help these public safety agencies arrive at informed, data-driven decisions.7

Working cooperatively with the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Massachusetts State Police’s firearms identification section and its crime laboratory, Boston Police Department, ATF, Massachusetts Criminal History Systems Board, and other local police agencies, CFC began collecting, processing, and analyzing crime and weapons-trace data to provide policy makers with data on firearms crime patterns, the types of weapons recovered at crime scenes or during arrests, and the source cities and states of these guns.

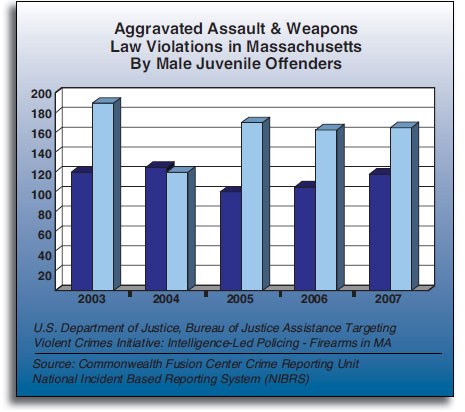

This project also has focused on leveraging existing information and supplementing it with new data to provide strategic and tactical intelligence to end users so that they can make informed decisions. The CFC serves as the state crime reporting repository using the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program’s National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) to collect crime information. This data provides details on crime incidents across jurisdictions on a year-to-year and month-tomonth basis and offers specifics on types of crime, such as aggravated assaults by firearm type and offender age and gender. For instance, the NIBRS data set allowed the CFC to closely examine firearms offenses committed by youths aged 10 to 17 across various communities to study juvenile gun crime.

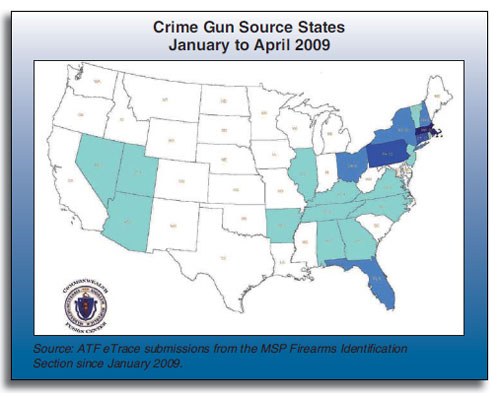

As another valuable source of information, the ATF’s National Tracing Center collects and disseminates data on firearms recovered from crimes. Participating police departments submit a request to ATF, which traces the origins of the firearm through various databases and then provides information on the first retail purchaser, the licensed dealer that sold the firearm, and the type and manufacturer of the weapon. This trace data provides both tactical and strategic intelligence to investigators, patrol officers, intelligence analysts, and decision makers. For instance, identifying the city and state of the first retail purchase of a firearm involved in a crime, as well as the amount of time elapsed between purchase and offense, provides a possible indicator of firearms trafficking.

In addition, the project has accessed summary data collected from the MSP crime laboratory and the state’s criminal justice information system to track firearms patterns in the commonwealth. These sources provide information on the varieties of weapons, types of crimes, and patterns of ownership for guns used in offenses. Employing these data sources— rarely used for analysis prior to this—the project determined the number of firearms recovered at crimes and identified the weapons’ journey to crime.

Fusing this criminal offense data with information on gun tracing, recovered firearms, and state weapon sales information provides investigators, police executives, and policy makers with a more comprehensive picture of firearms crimes in the state. Over the last year, the project has produced a number of intelligence briefs and analytical reports that outline gun violence by youth offenders or violent trends across communities.

The CFC disseminates intelligence briefs, analyses, and crime maps to policy makers and police administrators across the state to assist with resource deployment and the design of best practices to address firearms crime. In addition, the fusion center feeds these products back to information collectors, such as investigators and patrol officers, to reinforce their information-gathering efforts. This creates buy-in from collectors and illustrates the need for high-quality, accurate data.

“Fusion centers allow for the exchange of information and intelligence among law enforcement and public safety agencies at the federal, state, and local levels.”

As the map indicates, this type of data illustrates the geographic journey to crime for guns used in crimes in Massachusetts. Rather than confirming the common wisdom that only southern states fuel gun trafficking in Massachusetts, the project found that crime-related guns can originate from a number of states within the Northeast, the South, and beyond. This has important statewide implications for criminal justice policy.

CONCLUSION

The fusion center concept involving various criminal justice agencies opens a number of possibilities for enhancing intelligence-led policing. It establishes relationships among federal, state, and local agencies, which leads to improved information sharing and access to data that often was isolated in a single agency. It also brings together subject-matter expertise that provides a more relevant and credible intelligence end product. It creates buy-in from various agencies because they had input into its design.

This particular ILP project outlines a practical application of data fusion for traditional violent crime policy, easily transferable to homeland security and terrorism issues. Using existing and newly acquired data, fusion center analysts collect, process, analyze, and disseminate timely intelligence to decision makers at the federal, state, and local levels. More knowledgeable operational, strategic, and tactical deployment choices can be made on the basis of these data-driven products. This initiative provides an example of how data fusion and fusion centers can assist in everyday law enforcement challenges.

Endnotes

1 Bart Johnson, “A Look at Fusion Centers,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, December 2007, 28-32.

2 David Carter, “The Law Enforcement Intelligence Function: State, Local, and Tribal Agencies,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, June 2005, 1-9.

3 U.S. Department of Homeland Security and U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Fusion Center Guidelines: Developing and Sharing Information and Intelligence in a New Era (Washington, DC: 2006).

4 Fusion Center Guidelines.

5 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Navigating Your Agency’s Path to Intelligence-Led Policing (Washington, DC: 2009).

6 Navigating Your Agency’s Path to Intelligence-Led Policing.

7 Navigating Your Agency’s Path to Intelligence-Led Policing.