Investigating Scam Phone Calls

By Keven Hendricks

Police departments receive numerous reports of scams related to taxes or social security or perhaps schemes of some other sort. Often, these types of fraud target elderly or disabled individuals and involve perpetrators who claim to work for a government agency collecting money owed immediately.

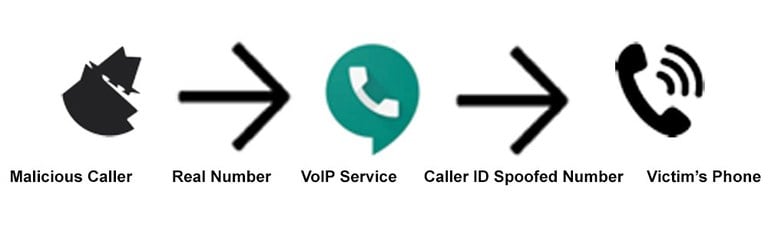

Scammers commonly use a technique known as “caller ID spoofing,” likely facilitated through abuse of a Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) service. This article aims to shed light on how these services work and what information is available for cases.

Modern Services

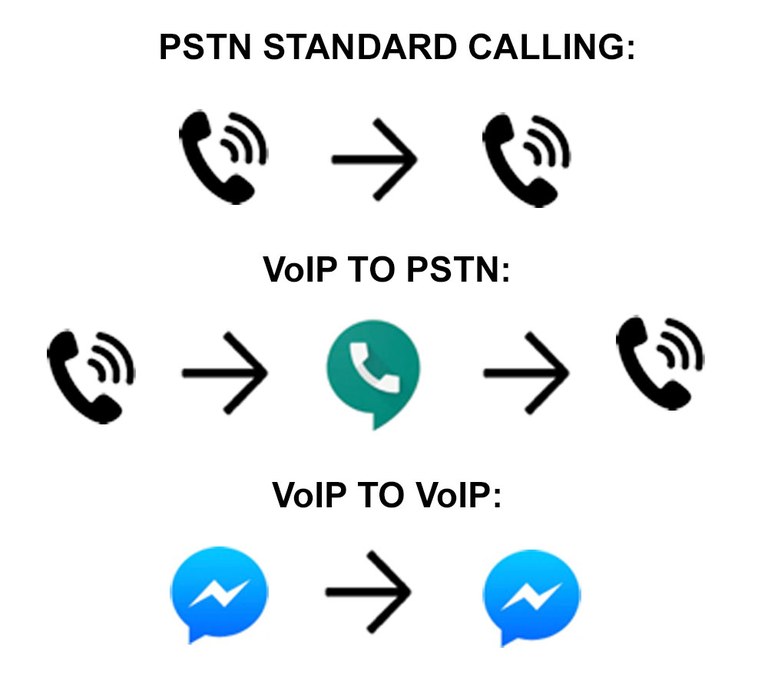

Understanding VoIP services requires fundamental knowledge of how phone calls—cellular or landline—work. Most go through the long-established Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) via one or more service providers.1 This system was designed and implemented at a time when these companies faced high barriers for entry; as a result, people trusted the connections made during calls.

However, much has changed in the last several decades, with Internet-based services growing in popularity and supplanting many traditional telephony technologies. While these new technologies have lowered costs and created a more communication-rich environment, they also allow communicating parties to mask or hide their identities.

Detective Hendricks, a certified cybercrime examiner and investigator, serves with the New Brunswick, New Jersey, Police Department and also works on a DEA cybercrime task force.

Opportunities to spoof, or fake, identifying information pertaining to communications on the PSTN become available when VoIP services interconnect with the traditional network. For instance, the Google Voice app, free with a verified Gmail account and active cellular service, allows a VoIP number to call and connect to landline and cell numbers that use the PSTN and lack VoIP capability. Services such as telzio and Grasshopper can be used similarly.

Spoofing Techniques

Victims may contact law enforcement after encountering scammers who abuse VoIP services to engage in caller ID spoofing. In this well-known tradecraft of telephonic scams, a suspect spoofs the caller ID of the victim’s phone so as to appear as a caller from a legitimate number, perhaps associated with a bank or government agency. This practice violates the Truth in Caller ID Act, in which the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) prohibits “…transmitting misleading or inaccurate caller ID information with the intent to defraud, cause harm, or wrongfully obtain anything of value.”2

Investigators should gain an understanding of how caller IDs work. Traditionally, when someone places a phone call via the PSTN, the originating service provider (OSP) populates information from its system into the signaling to identify the initiating party’s phone number. Today, the OSP may be a VoIP provider that does not validate the data, which allows customers to provide false or misleading information.

Then, the calls are routed through the PSTN and transmitted to the terminating service provider (TSP), which services the subscriber receiving the phone call. The TSP connects the subscriber’s call and uses—without validation—the information populated by the OSP to identify the caller. This originating party identification data is forwarded to the subscriber’s phone and reflected by the receiving party’s caller ID unit.

Currently, some major service providers are setting up techniques to mitigate the threat of spoofed calls from VoIP services by informing subscribers that an incoming call may present a fraud risk due to previously seen activity on their networks.

Investigative Approaches

When assigned a case involving a spoofed phone call—for instance, an individual fell victim to a scam resulting in monetary loss or somebody called in a bomb threat to a school—where do investigators begin?

They should start by obtaining the call detail records (CDRs) for the victim’s phone, landline or cell. These records may contain information about how the call was routed through the PSTN and, in turn, identify the OSP. While the originating number could be spoofed, the OSP may have additional details that will help reveal true information pertaining to the call’s originator. Although not always successful, this is a wise first step.

While investigating malicious calls facilitated through cellphone apps, a simple open-source search of the phone number displayed on the CDR may reveal it as an intermediary calling service for the app. Or, it could be a VoIP number (via providers such as Bandwidth or Inteliquent). Unfortunately, some services do not maintain subscriber information.

“Scammers commonly use a technique known as “caller ID spoofing,” likely facilitated through abuse of a Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) service.”

Ideally, the CDR will identify the originating provider or intermediary that ultimately can lead investigators to the communication’s source. However, investigators may encounter services, such as GlobalPOPs or Twilio, that offer wholesale providers for VoIP users. If the company is based in the United States, investigators should proceed with legal notice to obtain information pertaining to the call. In turn, this will lead to another service that also will respond to legal notice.3

Additionally, some of these companies require subscription payments because they can make calls to authentic numbers, often involving another service to facilitate these contacts. Such companies require a nondisclosure order due to applicable state laws to prevent them from notifying the suspect.

By following this process, investigators can find valuable information, such as the number that called the service, subscriber payment information, and even perhaps the International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) number or media access control (MAC) address associated with the phone if an app is installed.4

Investigators also should provide case details to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3).5 Similar cases likely exist, and IC3 will use this data to identify criminal enterprises. For instances of “swatting,” bomb threats, and other threatening acts, investigators should notify proper channels to ensure their regional intelligence center is aware of the case.6

Conclusion

Cases involving spoofed caller IDs derived from the misuse of VoIP services can prove challenging, but they are not insurmountable. Of course, international numbers and service providers can present additional obstacles, but investigators must remain confident.

Law enforcement officers may mistakenly believe that nothing can be done on the local level. Such officers run the risk of disenfranchising victims and, thus, discouraging them from calling the police in the first place. Further, they risk emboldening perpetrators to continue their nefarious ways.

Conversely, officers can navigate these cases successfully, investigate the crimes, bring perpetrators to justice, and protect the people they serve.

“While these new technologies have lowered costs and created a more communication-rich environment, they also allow communicating parties to mask or hide their identities.”

Detective Hendricks can be reached at Keven.Hendricks@leo.gov.

Endnotes

1 For additional information, see “PSTN (Public Switched Telephone Network),” Lifewire, June 24, 2019, accessed November 19, 2019, https://www.lifewire.com/pstn-public-switched-telephone-network-818168.

2 Truth in Caller ID Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 111-331 (2010), accessed November 19, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-bill/30.

3 For information on where to serve legal notice, see “ISP List,” accessed November 19, 2019, https//www.search.org/resources/isp-list/.

4 For further information on IMEIs, see Miguel Leiva-Gomez, “Everything You Should Know About Your IMEI Number,” maketecheasier, August 6, 2018, accessed November 19, 2019, https://www.maketecheasier.com/imei-number/; and for MAC addresses, “Difference Between MAC Address and IP Address,” TechDifferences, August 10, 2016, accessed November 19, 2019, https://techdifferences.com/difference-between-mac-and-ip-address.html.

5 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), accessed November 19, 2019, https://www.ic3.gov.

6 For additional information on swatting, see Dakin Andone, “Swatting Is a Dangerous Prank with Potentially Deadly Consequences. Here’s What You Need to Know,” CNN, March 30, 2019, accessed November 19, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/03/30/us/swatting-what-is-explained/index.html.