Leadership Storytelling

By Lance Lamoreaux, M.L.S., and Mari Shine, M.Ed.

Stories are a powerful tool to connect with and be inspired by others. As such, they are the best, most impactful way to persuade someone. A compelling, well-crafted narrative unites an idea with an emotion, motivating and influencing listeners much more than statistics and data.1 For example, a story of one starving child can inspire action to a greater degree than simply sharing about the number of hungry children in the world.

While storytelling does not solve all leadership challenges, it is a valuable aid in several leadership tasks, including sharing a vision, leading change, building trust, improving engagement, imparting knowledge, and addressing conflict.2

History

Storytelling is an ancient practice. Wisdom, advice, culture, history, and explanations were all shared through stories. This is why ancient religious accounts, origin stories, fairy tales, and fables exist. Although the history of storytelling is rich, it is often underutilized in leadership.

Through stories, leaders feel empowered to share their organization’s mission, vision, and ideas in a compelling, memorable, and interesting way. Empirical research shows that highly influential educational leaders are usually talented storytellers.3 For centuries, Native American Ute tribes have promoted their best storytellers to leaders.4 In business, many executives of the world’s most successful companies proactively tell stories to inspire and influence employees.5

Physiological Influence

Storytelling is powerful because of its impact on the brain in four key ways: neural activity, neural coupling, memory, and trust.

Neural Activity

Functional MRI machines show what happens to the brain when it receives different types of information. When processing facts, only a small portion of the brain lights up with neural activity, merely decoding the words into their dictionary meaning. But, when listening to a story, many other parts of the brain are engaged.6

Neural Coupling

Neuroscientists have discovered that those listening to a story synchronize their brains with the person telling it. This is called neural coupling, where the neural patterns in the listener’s brain match those of the speaker’s, creating a connection between both brains.7

Mr. Lamoreaux is a supervisory program manager and leadership instructor in the FBI’s Leadership Development Unit in Quantico, Virginia.

Ms. Shine is a program manager and leadership instructor in the FBI’s Leadership Development Unit in Quantico, Virginia.

Memory

Leadership messages will lack influence if forgotten. During lectures, talks, or meetings, dates and facts are difficult to recall, but a story and its takeaway might be memorable. This is because stories cause the brain to release dopamine, which, when combined with neural coupling and mirroring, improves memory by 22 times compared with data alone.8 Further, the brain can remember and connect distant and disjointed events into a cohesive narrative when told through stories.9

Trust

Listening to a story causes the brain to release oxytocin, creating trust in and increased empathy toward the storyteller.10 Vulnerability also builds trust. Leaders connect best with their team when they talk about their mistakes, challenges, and lessons learned. Heads of large departments can use narratives to develop trust since it may be impossible to get to know each employee.

Framework

Telling a story does not need to entail some miraculous feat. A simple framework involves setting the scene, defining the main character, stating the problem, explaining how it was overcome, and sharing the lesson learned.11

Setting

Listeners need to visualize the story in their minds. Anchoring the narrative to a location can capture the audience because it helps them feel as if they were there. This is a key distinction between a story and a recitation of facts.

A story should begin with a detailed and descriptive account of the setting. For example, instead of saying, “I called a staff meeting to discuss a new policy,” immerse the audience by saying, “I’m sitting at the head of a conference table surrounded by my command staff, and I can feel my face turning redder and redder.” This helps listeners stay engaged and interested.

Main Character

Ideally, this would be the leader. Telling an authentic story about a personal or professional experience increases vulnerability and helps to connect with employees.12 The result is increased trust, familiarity, and understanding.

At times, the most appropriate story is someone else’s, especially one from history. If such is the case, leaders should let their audience know it is a secondhand story to avoid losing trust.

Problem

Every impactful story contains a problem the main character attempts to overcome. An account about how awesome the leader is will not motivate anyone. The problem or challenge makes the narrative interesting. This is also a time to build curiosity. It is important for the storyteller to illustrate the struggle and how they felt about it.

The leader should describe the steps taken to overcome the problem. Continued failure during this step adds texture to the story.

Lesson Learned

Stories must contain a moment of transformation or realization.13 A simple anecdote involving a typical occurrence (e.g., leaving headphones on an airplane) can be compelling and effective if there is a meaningful lesson for the audience. Leaders must tell their team what they want them to take away from the narrative. Otherwise, the story’s purpose may be misinterpreted.

“A compelling, well-crafted narrative unites an idea with an emotion, motivating and influencing listeners much more than statistics and data.”

Considerations

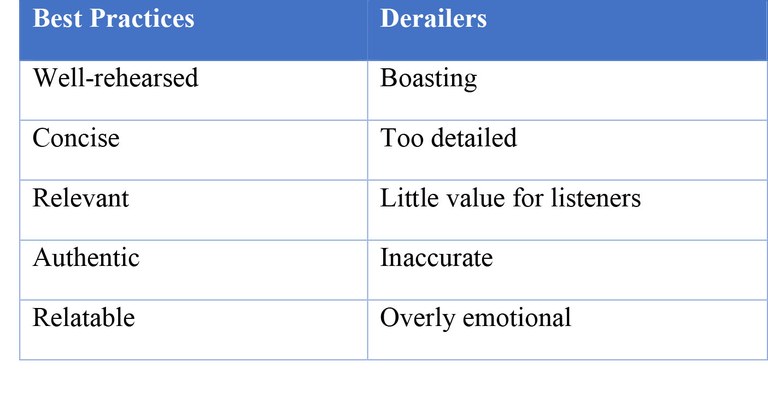

To tell effective leadership stories, there are a few best practices and derailers to consider.14

“Telling a story … involves setting the scene, defining the main character, stating the problem, explaining how the problem was overcome, and sharing the lesson learned.”

Leaders should also empower others to tell stories that align with the organization’s intended culture. For example, before a meeting, someone could be invited to tell a story about a time they witnessed the agency at its best, an ethical dilemma, or why they chose a career in law enforcement.

One bestselling novelist gave the key to telling a great story: “It cannot be about anything big. Instead, we must find the small, relatable, comprehensible moments in our larger stories. We must find the piece of the story that people can connect to, relate to, and understand.”15

Example

A surveillance team leader shared the following story during a team meeting because the cases had become slow and tedious. He sensed that he, along with the rest of his team, was becoming complacent.

Sitting on my cot at the end of the day, I still need to clean my weapon before finally getting some sleep. In the morning, I leave for my first combat mission as a U.S. Marine deployed to western Iraq. It has been an exhausting day ensuring the platoon is prepared.

I open my weapon, visually inspect the bolt, and run my finger inside looking for dirt. I think to myself, “It’s clean.” Slamming the bolt back, I replace the pins and set the weapon aside to go to sleep.

The following morning, as we leave the base at “zero dark thirty,” we stop at a large dirt berm. Everyone exits their trucks and loads their weapons. I walk up to the berm, pull back on the charging handle, release it, and the bullet jams. A wave of fear, anger, and adrenaline flows through my body. I dislodge the bullet and try again. But, to my chagrin, the bullet jams again.

Most people have returned to their trucks. As a leader, I failed to lead by example. For the third time, I clear the jam, pull back on the charging handle, and success! The fear I once felt changed to relief, and I return to my truck.

As the convoy exits the base, I see the phrase “COMPLACENCY KILLS” spray-painted on a cement barrier. After my embarrassing and potentially dangerous experience at the berm, these words left an indelible impact on me.

As a team, we must ensure that we are not complacent like I was in not thoroughly cleaning my rifle. The cases are slow, but we must do our best.

After the leader shared this story, the team’s collective attitude immediately changed. People remembered the story and brought it up months later. If he had just said, “Let’s make sure we are not complacent out there,” that statement would not have left the same impression. Several years later, a team member foresaw an operational issue. The leader asked what motivated him to act, and he responded that he did not want to be complacent like the leader had been in his story.

Conclusion

Developing storytelling skills will enable leaders to make a positive impact. The mission and vision become clearer, change initiatives are better understood and embraced, and employees are more inspired by the work. A team is more likely to trust its leader and remember the intended message when it is conveyed through a story.

“A team is more likely to trust its leader and remember the intended message when it is conveyed through a story.”

Mr. Lamoreaux can be reached at ldlamoreaux@fbi.gov and Ms. Shine at mmshine@fbi.gov.

Endnotes

1 Bronwyn Fryer, “Storytelling That Moves People,” Harvard Business Review, June 2003, https://hbr.org/2003/06/storytelling-that-moves-people.

2 Shannon Cleverley-Thompson, “Teaching Storytelling as a Leadership Practice,” Journal of Leadership Education 17, no. 1 (January 2018): 132-140, https://doi.org/10.12806/v17/i1/a1.

3 Barry Aidman and Tanya Alyson Long, “Leadership and Storytelling: Promoting a Culture of Learning, Positive Change, and Community,” Leadership and Research in Education 4, no. 1 (2017): 106-126, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1160822.pdf.

4 Paul Smith, Lead with a Story: A Guide to Crafting Business Narratives That Captivate, Convince, and Inspire (New York: American Management Association, 2012).

5 Francesca Gino, “The Unexpected Influence of Stories Told at Work,” Harvard Business Review, September 15, 2015, https://hbr.org/2015/09/the-unexpected-influence-of-stories-told-at-work.

6 Alan Quintero, “The Power of Storytelling,” Linkedin, March 30, 2017, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/power-storytelling-alan-quintero; and Susana Martinez-Conde et al., “The Storytelling Brain: How Neuroscience Stories Help Bridge the Gap Between Research and Society,” Journal of Neuroscience 39, no. 42 (October 2019): 8285-8290, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1180-19.2019.

7 Uri Hasson et al., “Brain-to-Brain Coupling: A Mechanism for Creating and Sharing a Social World,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16, no. 2 (February 2012): 114-121, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.007; and Greg Stephens, Lauren Silbert, and Uri Hasson, “Speaker-Listener Neural Coupling Underlies Successful Communication,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, no. 32 (July 2010): 14425-14430, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1008662107.

8 Quintero.

9 Christopher Bergland, “How Storytelling Narratives Come Together Inside the Brain,” Psychology Today, September 29, 2021, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-athletes-way/202109/how-storytelling-narratives-come-together-inside-the-brain.

10 Tanya Procyshyn, Neil Watson, and Bernard Crespi, “Experimental Empathy Induction Promotes Oxytocin Increases and Testosterone Decreases,” Hormones and Behavior 117 (January 2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2019.104607.

11 Fryer; Cleverley-Thompson; Stephen Denning, The Leader's Guide to Storytelling: Mastering the Art and Discipline of Business Narrative (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2005); Stephen Denning, The Springboard: How Storytelling Ignites Action in Knowledge-Era Organizations (London: Routledge, 2011); Matthew Dicks, Storyworthy: Engage, Teach, Persuade, and Change Your Life Through the Power of Storytelling (Novato, CA: New World Library, 2018); and Kindra Hall, Stories That Stick: How Storytelling Can Captivate Customers, Influence Audiences, and Transform Your Business (New York: HarperCollins, 2019).

12 Aidman and Long, 112.

13 Dicks.

14 Denning, The Springboard.

15 Dicks.