Leveraging Data to Predict Outcomes in Hostage and Barricade Incidents

By Timothy C. Healy, M.A., Daniel J. Neller, Psy.D., and Mark W. Flores

Two Arizona prison inmates violently overpower corrections officers and take two guards captive, barricading themselves in a guard tower and brandishing weapons. During 15 days of negotiations, the inmates use the hostages to keep tactical teams at bay.1

An Alabama man kills a school bus driver and takes a 5-year-old boy hostage, then barricades himself and the child in an underground bunker wired with explosives. After seven days of negotiations, the subject escalates his threats and promises death if authorities do not meet his demands.2

In Mississippi, a suspect kills a young girl’s father, then barricades himself with the girl inside the residence. During two days of negotiations, the armed subject allows the girl to speak to police over the phone while he aims a pistol at her.3

Learning to Assess Crises

If officers responded to one of these incidents, how would they assess it? How would they appraise violence risk to law enforcement officers, hostages, barricade victims, or others? How would they estimate the probability of successful resolution by negotiation or surrender? On what would they base their assessment and decisions — prior training, previous experience, gut feeling, teammates’ opinions, expert consultation, or something else?

The FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit (CNU) has instructed generations of negotiators on how to assess indicators of progress and violence risk in hostage and barricade incidents. Consistent with best practices across several areas of prediction, CNU teaches negotiators to consider both static (i.e., unchangeable) and dynamic (i.e., changeable) variables when conducting such assessments.

Without question, CNU’s approach has helped countless negotiators and incident commanders structure their appraisals of the most likely outcomes of crisis incidents. Yet, offering numerical probabilities with reasonable confidence has remained elusive — until now.

Using New Tools

Based on rigorous statistical analyses of 7,216 hostage and barricade incident reports covering a 35-year period, CNU has incorporated two tools that aid in assessing important outcomes of crisis incidents. Tool 1 estimates the probability that an incident will involve violence after its onset. Tool 2 assesses the probability that an incident will successfully resolve by negotiation or surrender.

Each contains eight items that a negotiation team can respond to within minutes, enabling members to rapidly assess an incident in the field. Both are statistically validated across several large samples, timeframes, and geographic locations and are reasonably accurate. Tool 1 correctly predicts violence after onset in 4 out of every 5 incidents, and tool 2 correctly predicts successful resolution by negotiation or surrender in 2 out of every 3 incidents.

Supervisory Special Agent Healy serves with the FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit in Quantico, Virginia.

Dr. Neller is a board-certified forensic psychologist based out of North Carolina.

Mr. Flores, a retired supervisory special agent from the FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit, currently serves as watch commander at the bureau’s Strategic Information and Operations Center.

Data-Driven Prediction of Outcomes in Hostage and Barricade Incidents

A couple of comparisons may put the tools’ high accuracy rates into perspective. Statistically, the correlations between the tools’ scores and crisis incident outcomes are about as strong as those observed between standardized test scores and academic performance in college and graduate school. Further, they appear capable of predicting outcomes in crisis incidents almost as well as mammograms predict breast cancer.4

This level of accuracy enables law enforcement to assess a crisis and, based on statistical analyses of thousands of cases across the United States, assert with reasonable confidence, “An incident with these features tends to involve violence after onset X% of the time and successfully resolve by negotiation or surrender Y% of the time.”

Finding Success

CNU’s innovative tools resulted from a collaborative effort that began in 2012, when a special agent invited a forensic psychologist to help teach law enforcement to assess violence risk in crisis incidents. The forensic psychologist off-handedly remarked that CNU could use the thousands of incident reports contained in the FBI’s Hostage Barricade Database System (HOBAS) to improve the prediction of outcomes in crises. Immediately, the agent set the project in motion.

Three teammates joined them — another FBI agent who teaches graduate-level statistics, an FBI victim services psychologist who teaches criminology, and a data analyst who works in the private sector. The Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG) facilitated the first meeting at the FBI’s Denver office in 2014 and, along with an interagency partner, offered ongoing, steady support until the tools were finalized in 2020.

A technical write-up of the project was recently published in an international peer-reviewed journal.5 The article has already generated positive responses from law enforcement and other professionals outside the United States.

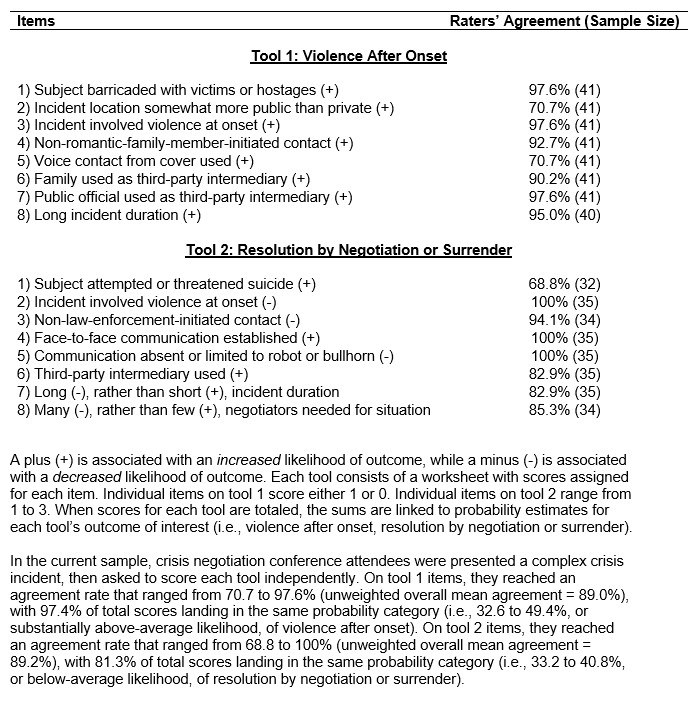

In addition, CNU introduced a 45-minute instruction block to teach law enforcement officers about the tools during its annual Crisis Negotiations Coordinator Conference (CNC). Attendees provided overwhelmingly positive feedback on the tools’ practical usefulness, and they contributed to CNU’s growing understanding of the tools’ statistical properties. A sample of CNC attendees provided preliminary evidence that, when presented with a complex historical scenario, law enforcement officers can independently agree on how each item should be scored about 90% of the time (see table).

For illustrative purposes, CNU has also applied the two tools retrospectively to three crisis incidents that are well-known to crisis negotiators and commonly used as case studies in training scenarios.

A) 2013 Midland City, Alabama, underground bunker hostage incident, briefly discussed at the beginning of the article

B) 1999 St. Martin Parish, Louisiana, prison takeover by eight Cuban inmates, which resolved following six days of negotiation6

C) 1996 Honolulu Seal Masters of Hawaii hostage incident, a six-hour standoff that resolved via tactical action7

“ … offering numerical probabilities with reasonable confidence has remained elusive — until now.”

Tool 1 correctly indicated the risk for violence after onset was substantially above average for each incident. Tool 2 indicated the likelihood of resolution by negotiation or surrender was below average for incidents A and C and as average for incident B.

Conclusion

Although current research indicates both tools can be reliably scored and are reasonably accurate in predicting outcomes, incident commanders are discouraged from using them as substitutes for professional judgments or continuous assessments. Rather, the tools should be used as aids to make informed, defensible, and data-driven decisions in hostage and barricade incidents.

Additional research will help users better understand the tools’ accuracy, usefulness, strengths, and limitations. The FBI’s Crisis Negotiation Unit intends to continue to conduct research on the tools, offer training on them, and solicit ongoing feedback from local and state law enforcement partners.

“Each [tool] contains eight items that a negotiation team can respond to within minutes, enabling members to rapidly assess an incident in the field.”

Law enforcement professionals and researchers can obtain the tools by contacting Supervisory Special Agent Healy at tchealy@fbi.gov. Dr. Neller can be reached at danieljneller@gmail.com and Mr. Flores at mwflores@fbi.gov.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this manuscript are the authors’ and are not necessarily shared by the U.S. government, U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, or any other organization with which they are affiliated.

Endnotes

1 Courtland Jeffrey, “Old Time Crime: Longest Prison Hostage Standoff in U.S. Took Place in Buckeye in 2004,” ABC 15 Arizona, January 14, 2018, https://www.abc15.com/news/region-west-valley/buckeye/old-time-crime-longest-prison-hostage-standoff-in-u-s-begins-in-buckeye-in-2004.

2 Associated Press, “Authorities Storm Alabama Man’s Hideout, Rescue 5-Year-Old Boy,” Florida Times-Union, February 5, 2013, https://www.jacksonville.com/story/news/crime/2013/02/05/authorities-storm-alabama-mans-hideout-rescue-5-year-old-boy/15839174007/.

3 William Moore and Teresa Blake, “10-Year-Old Girl Safe After 32-Hour Hostage Situation,” Itawamba County (MS) Times, December 31, 2018, https://www.djournal.com/news/10-year-old-girl-safe-after-32-hour-hostage-situation/article_fa53e25d-eaa5-5cb0-b82e-de9a71b0e84e.html.

4 Gregory J. Meyer et al., “Psychological Testing and Psychological Assessment: A Review of Evidence and Issues,” American Psychologist 56, no. 2 (February 2001): 128-165, https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.128.

5 Daniel J. Neller et al., “Situational Predictors of Negotiation and Violence in Hostage and Barricade Incidents,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 48, no. 12 (2021): 1770-1787, https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548211017926.

6 Britt Lofaso, “20 Years Ago: Woman Recalls Being Taken Hostage by Inmates in St. Martin Parish Jail,” KLFY.com, December 19, 2019, https://www.klfy.com/top-stories-news/hostage-recalls-being-taken-prisoner-by-inmates-in-st-martin-parish-jail-20-years-ago/.

7 Mary Vorsino, “20 Years Ago, a Sand Island Standoff Riveted Hawaii TV Viewers,” Hawaii News Now, February 6, 2016, https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/story/31157308/20-years-ago-a-sand-island-standoff-riveted-hawaii-tv-viewers/.