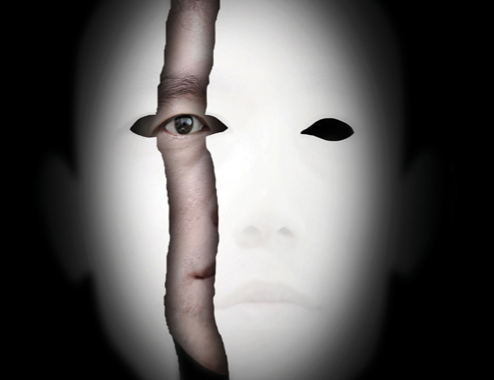

Looking Behind the Mask

Implications for Interviewing Psychopaths

By Mary Ellen O’Toole, Ph.D.; Matt Logan, Ph.D.; and Sharon Smith, Ph.D.

Gary Leon Ridgway, the infamous Green River Killer, sat calmly as he casually described how he murdered, sexually violated, and disposed of the bodies of at least 48 women in King County, Washington.1 He talked about his victims as mere objects, not human beings. He said things, like “I feel bad for the victims,” and even cried at times. However, genuine feelings of remorse for his actions and empathy for the pain he caused the victims and their families were absent. Like many serial sexual killers, Ridgway exhibited many of the traits and characteristics of psychopathy that emerged in his words and behaviors during his interviews with law enforcement.

Ridgway had a lot to lose by talking to investigators. So, why did one of America’s most prolific serial sexual killers spend nearly 6 months talking about his criminal career that involved egregious and sexually deviant behavior? Because of the strategies investigators employed to look behind the mask into the psychopathic personality, Ridgway was highly motivated to take them inside his criminal mind.

The Interview Experience

There are no materials in criminology textbooks on interviewing an evil person or a monster, terms frequently used to describe a psychopath. These terms have no meaning in the legal or mental health nomenclature. A psychopathic individual is not necessarily evil nor a monster. A psychopath is someone with specific personality traits and characteristics.

Many law enforcement professionals consider themselves skilled interviewers because of their training and the volume of interviews they have conducted throughout their careers. However, when interviewing psychopaths, the dynamics change, and existing skills can prove inadequate. Interviews with these individuals quickly can derail unless investigators understand what to anticipate and how to use the psychopath’s own personality traits as tools to elicit information.

Psychopathic Traits

A knowledgeable investigator can identify a multitude of psychopathic traits and characteristics by reviewing crime scene information, file data, prior interviews, mental health assessments, and relevant information provided by associates and family members. When sorting through this documentation, interviewers should look for lifetime patterns of behavior that manifest traits of psychopathy.

Glib and Charming

Psychopaths often exude charm and charisma, making them compelling, likeable, and believable during interviews. They can display a sense of humor and be pleasant to talk with. Their charm allows them to feign concern and emotion, even crying while they profess their innocence. Because it is in their best interest, throughout their lives they have convinced people that they have normal emotions. If they perceive that their charm is not working, it quickly will vanish, being replaced by a more aggressive or abrasive approach. Interviewers are inclined to lecture or scold the psychopath; however, these strategies likely will not work.

Psychopaths often appear at ease during interviews that most people would find stressful or overwhelming. Several explanations exist for their apparent lack of concern, including an absence of social anxiety. They seek or create exciting or risky situations that put them on the edge.

Interviewers often are nervous or anxious. During the first 5 minutes of the interview, when impressions are being formed, engaging in small talk, fidgeting with cell phones or notepads, or showing uncertainty regarding seating arrangements can communicate to psychopaths that interrogators are nervous or unsure of themselves. Psychopathic individuals view this as a weakness.

Stimulation Seeking

Their need for stimulation and proneness to boredom means psychopaths often become disinterested, distracted, or disconnected during interviews. A single investigator may not provide sufficient stimulation and challenge. Consequently, the dynamics need to change to keep the psychopathic offender engaged. This may involve using multiple interviewers, switching topics, or varying approaches. The interviewer’s strategies may include using photographs or writings to supplement a question-and-answer format, letting suspects write down ideas and comments for discussion, or having the psychopath act as a teacher giving a course about criminal behavior and providing opinions about the crime.

Narcissistic

A psychopath’s inherent narcissism, selfishness, and grandiosity comprise foundations for theme building. Premises used in past successful interviews of psychopathic serial killers focused on praising their intelligence, cleverness, and skill in evading capture as compared with other serial killers.2 Because of psychopaths’ inflated sense of self worth and importance, interviewers should anticipate that these suspects will feel superior to them. Psychopathic individuals’ arrogance makes them appear pseudointellectual or reflects a duping delight—enjoyment at playing a cat-and-mouse game with the interrogator.

Stressing the seriousness of the crime is a waste of time with psychopathic suspects. They do not care. As distasteful as it might be, investigators should be prepared to stroke psychopaths’ egos and provide them with a platform to brag and pontificate. It is better to emphasize their unique ability to devise such an impressive crime, execute and narrate the act, evade capture, trump investigators, and generate media interest about themselves.

Irresponsible

The possibility that psychopaths’ actions may result in them going to jail has little impact on their decisions. Therefore, pointing out the consequences of their behavior will not work. Their unrealistic goal setting causes many psychopathic offenders to believe they will escape charges, win an appeal, have a new trial, or receive an acquittal. Unable to accept blame, these individuals quickly minimize their involvement in anything that negatively reflects on them. They usually avoid responsibility for their actions and frequently deny that real problems exist. Investigators can connect with psychopathic offenders by minimizing the problem or the extent of the damage. This facilitates the suspect’s disclosure of details about the offense.

Pathologically Deceptive and Manipulative

Most psychopaths are pathological liars who will lie for the sake of getting away with it. They will lie about anything, even issues that are insignificant to the crime or investigation. Lying is not a concern for them, and they do not feel anxious or guilty about doing it. Challenging a psychopathic individual’s statements will be counterproductive, especially if done too early in the interview. Investigators should keep psychopaths talking so their contradictions and inconsistencies mount. Their arrogance and impulsive nature result in bragging, preaching, trying to make an impression, or just showing off. This is when they slip and provide important information about themselves and their crimes.

Interviewers should be prepared for a psychopathic suspect to hijack the interview by bringing up topics that have nothing to do with the crime. This can result in a loss of valuable time. To bring the discussion back on track an interrogator could say “You raise important issues that I had not thought of, but right now I want to get back to discussing the crime.”

Predator

“…when interviewing psychopaths, the dynamics change, and existing skills can prove inadequate.”

Generally, psychopaths are predators who view others around them as prey. Whether the suspect is dressed in a suit or in dirty, ragged street clothes, this mind-set carries over and impacts the interview. This means the psychopathic individual may attempt to invade the interviewer’s personal space. These offenders might note and react negatively when interrogators write things down and when they do not. They will watch the interrogator’s behavior for signs of nervousness, anxiety, frustration, and anger and react to those signs. Psychopaths use what they can to their advantage.

While incarcerated in San Quentin State Prison in California, infamous cult leader Charles Manson participated in an on-camera interview with a well-known national news correspondent. Prior to the interview, prison officers set up the room and told Manson where to sit. There were three armed correctional officers present to monitor Manson’s behavior. Upon entering the room, Manson immediately walked around the tables to the other side where the reporter stood. He physically leaned into the reporter, touched him on his shoulders, and shook his hand. This display of arrogance, dominance, and invasion of personal space, which took less than 1 minute, caught the reporter completely off guard. When they sat down, in an effort to build rapport, the correspondent tried to talk with Manson about the beautiful California weather. Manson ignored him, but said that he had just come out of solitary confinement. The reporter asked Manson to talk about a routine day there at the prison.

Some interviewers would reprehend Manson on his behavior, order him to the other side of the room, and let him know who is in charge. Invading another’s space and trying to take charge are behaviors that a psychopath will exhibit throughout an interview. Investigators should anticipate these actions.

Manson had just come out of solitary confinement, where he likely was bored. Asking what his routine was like would have catapulted Manson back into a state of mind—boredom—inconsistent with a psychopath’s need for thrill and excitement. Manson’s actions suggested that he needed to feel dominant and in control. In this case, an interviewer could have focused on Manson and let him feel that he decided the topic by asking open-ended questions, such as “What do you want to talk about?” Interrogators needed to minimize personal views and insights; seek Manson’s opinion; and ask about his greatness, crimes, and notoriety compared with others. Law enforcement officers should be aware of the psychopath’s early onset boredom and be prepared to incorporate strategies to keep the individual stimulated and interested.

Unremorseful and Nonempathetic

Psychopathic offenders are not sensitive to altruistic interview themes, such as empathy for their victims or remorse over their crimes. Their concern is for themselves and the impact the meeting will have on them. Psychopaths blame their victims for what happened and consider the victims’ fate irrelevant.

Many psychopaths have the intellect to understand that others experience strong emotions. These individuals have learned to simulate sentiment to get what they want. When pressed to explain in detail their feelings about their victim, the crime, or the damage caused, a psychopath’s words, descriptors, and concomitant behaviors will be lacking.

Throughout the interview, interrogators should include detailed questions about the psychopath’s emotions, such as “How did you feel when you learned the police were investigating you?” or “What do sadness and regret feel like to you?” Probing with emotional questions likely will rattle and frustrate psychopaths because they cannot explain feelings they do not have or consider important. Often, these questions evoke agitated responses that are helpful to interviewers.

After asking feeling questions, interviewers should pose intellectual ones about the crime scene, victim, or offense, suggesting that mistakes occurred during the crime. The combination of frustration with emotional questions and inferences of a flawed crime will result in irritation because psychopaths’ grandiosity in thinking means that they feel they do not make mistakes. This annoyance results in psychopaths making impulsive, uncensored statements that may help investigators.

Rapport Building

Interviewers establish trust and bond with psychopaths by finding common ground. This involves disclosing personal information, including opinions, thoughts, observations, and feelings. Bonding or emotionally connecting with psychopathic individuals does not work because they have a myopic view of a world that revolves solely around them. They do not care about the interviewer’s feelings or personal experiences. Interviewers must connect with psychopaths by making them think the interview is about them.

Conclusion

Through their behavior, psychopaths’ convince interviewers that they have remorse when they have none and that they feel guilt when they do not. Their glib and charming style causes law enforcement officers to believe the suspects were not involved in the crime. The psychopathic individual’s grandiosity and arrogance offends investigators. Their pathological lying frustrates and derails the interviewer’s best efforts. However, with the proper preparation, knowledge, and understanding of psychopathy, law enforcement investigators can go behind the mask and see the true psychopathic personality beneath. Using dynamic and subtly changing strategies during interviews can create an environment where psychopaths less likely will predict the next steps and more likely will talk about their offenses and criminal superiority.

“Psychopaths blame their victims for what happened and consider the victims’ fate irrelevant.”

Dr. O’Toole has served with the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit and is a private forensic behavioral consultant and an instructor at the FBI Academy.

Dr. Logan, a retired staff sergeant with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and a psychologist, provides forensic behavioral consultation and training for the law enforcement and criminal justice communities.

Dr. Smith, a retired special agent with the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, is a consultant on criminal and corporate psychopathy for intelligence- and security-related government and law enforcement agencies.

Endnotes

1 King County Sheriff’s Office, “Green River Homicides Investigation,” http://www.kingcounty.gov/ safety/sheriff/Enforcement/Investigations/GreenRiver/aspx (accessed January 30, 2012).

2 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Serial Murder: Multidisciplinary Perspectives for Investigators (Washington, DC, 2005), http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/ publications/serial-murder (accessed January 18, 2012).

Additional Resources

H. Cleckley, The Mask of Sanity (St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1982)

R.D. Hare, The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multihealth Systems, 2003)

R.D. Hare, “Psychopaths and Their Nature: Implications for the Mental Health and Criminal Justice Systems,” in Psychopathy: Antisocial, Criminal, and Violent Behavior, ed. T. Millon, E. Simonson, M. Burket-Smith, and R. Davis (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 188-212

R.D. Hare and M.H. Logan, “Introducing Psychopathy to Policing,” in Psychologie de

L’enquête: Analyse du Comportement et Recherche de la Vérité, ed. M. St-Yves and M.

Tanguay (Quebec, PQ: Editions Yvon Blais, 2007)

M.H. Logan, R.D. Hare, and M.E. O’Toole, “The Psychopathic Offender,” The RCMP

Gazette, no. 66 (2005): 36-38

M.E. O’Toole, “Psychopathy as a Behavior Classification System for Violent and Serial Crime Scenes,” in The Psychopath: Theory, Research, and Practice, ed. H. Hervé and J. Yuille, (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, 2007), 301-325

U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Serial Murder: Multidisciplinary Perspectives for Investigators (Washington, D.C., 2005), http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/ publications/serial-murder