Optimizing Facebook for Public Assistance in Investigations

By Kimberly Brunell, J.D., and Sarah Craun, Ph.D.

Law enforcement agencies face a unique challenge when using social media platforms to request public assistance regarding important cases. Officers are trained to conduct thorough investigations and follow facts as they unfold, rather than communicate and market a message in a way that captures people’s attention and ultimately obtains their help.

Historically, departments have relied on traditional media outlets to take portions of their communications—often sound bites or quotes—and deliver them to the public. Sometimes, the edited version sounds better, but in other cases the intended message gets lost in translation.

When communicating with the public directly through social media, agencies must choose their words carefully—as they would with traditional media—to respect the privacy rights of victims, witnesses, and subjects; avoid harming a case referred for prosecution; and deliver the desired message.

To this end, the authors recently examined how departments can use social media most effectively and appropriately to procure the public’s help with investigations. They focused on the most commonly used site—Facebook.

Using the Platform

Data from the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) showed that 94 percent of departments have a Facebook page, 71 percent a Twitter account, and 10 percent a YouTube channel.1 Agencies use such social media sites for help with various tasks, such as recruitment, dissemination of crime prevention tips, community announcements, public relations, and requests for assistance from the public with investigations.2

Of the 76 percent of agencies that use social media to solicit tips about crimes, 95 percent employ Facebook.3 Public users generally have altruistic motives and either respond if they can help or share such posts so that even their distant connections on Facebook, not just their closest friends, will see the content.4

With so many departments using Facebook to reach these social media users, the authors wanted to determine the appropriate tone law enforcement should strive for to achieve the most widespread distribution of posts requesting assistance.

Adding Humor

One police department’s public relations official recommended that law enforcement agencies add humor to their Facebook pages and, further, that departments can improve their image by using humor while still managing the delicate balance required in public communications.5

Another agency provided an anecdotal illustration of how it caught three criminals by using humor, Facebook, and community assistance.

Three years ago, we would have been lucky to identify one out of the three involved. That is because of you. The Facebook reader, sharer and/or stalker. You know who you are. We have had a few laughs and at the same time we are closing out cases that would not have been possible in the past. We appreciate it. Thanks for helping us out and we feel strongly theft will no longer exist in 2017.6

“Historically, departments have relied on traditional media outlets….”

The authors sought to systematically determine: Is humor is the best way to learn additional information about an unsolved crime? Or, should agencies write posts soliciting crime tips in a way that makes people sad? Angry? Do the emotions elicited have any impact on how often users share the post?

Gaining Shares

Facebook offers users the ability to share their reaction to a post by clicking an associated icon—like, love, “haha,” “wow,” sad, or angry. This provides an effective proxy for the emotions that people experience.

The authors wanted to explore the relation between emotional reactions and the number of shares. With the support of the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division (CJIS), they randomly selected 100 law enforcement agencies that had active warrants in the National Crime Information Center (NCIC). They located each department’s Facebook page and examined the number of clicks for each emotion as well as the total shares pertaining to the 10 most recent requests for the public’s help.7

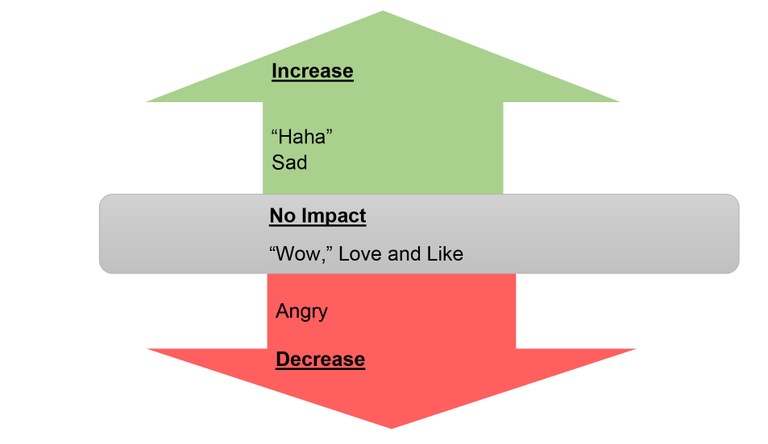

Among the 100 sampled agencies, the emotional impact of the post sometimes increased the number of shares. Each “haha” or “sad” click recorded under an investigative assistance post resulted in increased shares. However, a higher number of “angry” clicks correlated with a decreased number of shares. “Wow,” “love,” and “like” clicks had no impact.

These findings shed light on how agencies can write such posts on Facebook to reach the widest possible audience.

Impact of Emotions on the Number of Facebook Shares

“Among the 100 sampled agencies, the emotional impact of the post sometimes increased the number of shares.”

Results concerning the impact of emotions relate to all crime types. Additional research could explore how different combinations of emotions and crimes affect the number of shares. For example, using humor may lead to the most shares of posts pertaining to crimes like theft and burglary, while, conceivably, evoking sadness could result in more frequent shares of investigative requests relating to missing persons.

Moreover, it is easier to get a person to like a post than to share it.8 Because a reaction click or comment on a public Facebook post may make it appear on a friend’s news feed, future research should determine how to increase readers’ tendency to comment or click on any of the available reactions.

Analyzing Data

With tools such as Facebook Analytics, law enforcement agencies can take a data-based approach to decide which of the presented suggestions work best for obtaining public investigative assistance in their own jurisdiction. They can do this by reviewing such data as the viewer count for a post; total likes and shares; and number of people who have interacted negatively, such as hiding the page or reporting it as spam. Further, departments can examine how time of day affects the success of posts, who their audience is, and what other agencies are doing.9

Spreading the Message

Fortunately, some of the rules of traditional media apply when using social media. Be focused. Be concise. Do not mislead. Use crisp, high-impact words, not inflammatory ones. Do not condescend. Avoid police jargon and acronyms. Do not use big words, hoping to sound intelligent but perhaps confusing the reader.

When crafting a message with the right emotional tone, officers might become concerned about themselves as the author, even while following appropriate protocols. Instead, they should focus on the message’s consumers. In general, people care most about how a story impacts them and makes them feel.10 This could explain why agency requests for information regarding theft had the most shares; perhaps people see themselves as most likely to become a victim of property crime.

Posts requesting information without specifying a crime, which also had a high number of shares, have benefited from the marketing principle of subtlety—less can be more. In other words, the fewer details departments reveal about an investigation, the more powerful the story becomes. Agencies are fortunate from an attention-seeking perspective in that many of their cases offer stories interesting enough to tell as they are, and allowing the public to form their own conclusions sometimes can prove more effective.

Agencies also should ask directly for shares from the public in their posts. This creates a feeling of “deputization” and may lead to further distribution of the message. Additionally, IACP stresses the importance of both posting information about specific suspects and notifying the public when they are apprehended.11 Further, compelling photos can help increase shares.

Conclusion

Agencies can find something interesting or unique about any case. Officers should discuss publicizing investigations and perform a simple balancing test, weighing the risks against the need for public assistance. If the need for a tip is greater, they should craft a message and succinctly convey the essential idea in a way that the reader will absorb. Further, as social media platforms evolve over time, departments must change their practices accordingly.

“Fortunately, some of the rules of traditional media apply when using social media.”

Ms. Brunell, a retired supervisory special agent, serves with a private corporation as an associate director of a crisis and security consulting team. She can be contacted at Kimberly.brunell@controlrisks.com.

Dr. Craun is a research coordinator in the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit-5 in Quantico, Virginia. She can be contacted at swcraun@fbi.gov.

Endnotes

1 2015 Social Media Survey Results (Washington, DC: International Association of Chiefs of Police), accessed July 23, 2019, http://www.iacpsocialmedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/FULL-2015-Social-Media-Survey-Results.ressed.pdf.

2 Lori Brainard and Mariglynn Edlins, “Top 10 U.S. Municipal Police Departments and Their Social Media Usage,” The American Review of Public Administration 45, no. 6 (2015), accessed July 23, 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0275074014524478.

3 2015 Social Media Survey Results.

4 Pei-Wen Fu, Chi-Cheng Wu, and Yung-Jan Cho, “What Makes Users Share Content on Facebook? Compatibility Among Psychological Incentive, Social Capital Focus, and Content Type,” Computers in Human Behavior 67 (February 2017): 23-32, accessed July 23, 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.010.

5 Katie Nelson, “Finding Your Social Media Funny Bone,” The International Association of Chiefs of Police Official Blog, January 25, 2017.

6 Bangor, Maine, Police Department, Facebook post, May, 23, 2016, accessed July 24, 2019, https://www.facebook.com/bangormainepolice/.

7 This research occurred in 2017. While the data are approximately 3 years old, the behavior measured remains applicable today, with social media so abundant in modern life. For a more comprehensive description of the study’s methodology, see Kimberly F. Brunell, Sarah W. Craun, and Briana Davis, “The Relationship Between Facebook Reactions and Sharing Investigative Requests for Assistance,” Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, November 7, 2018, accessed July 24, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9297-6.

8 Saleem Alhabash, Anna R. McAlister, Chen Lou, and Amy Hagerstrom, “From Clicks to Behaviors: The Mediating Effect of Intentions to Like, Share, and Comment on the Relationship Between Message Evaluations and Offline Behavioral Intentions,” Journal of Interactive Advertising 15, no. 2 (2015): 82-96, accessed July 24, 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2015.1071677.

9 For additional information, see “Facebook Analytics,” Facebook, accessed August 5, 2019, https://analytics.facebook.com/.

10 Seth Godin, All Marketers Tell Stories (New York, NY: Penguin, 2012).

11 Building Your Presence with Facebook Pages: A Guide for Police Departments (Washington, DC: International Association of Chiefs of Police), accessed July 24, 2019, http://www.iacpsocialmedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/FacebookPagesGuide.pdf.