Performance Management Strategies for Effective Leadership

An Accountability Process

By Gary Ellis, Ph.D., and Anthony H. Normore, Ph.D.

An organization is only as good as the sum of its parts, and in law enforcement agencies these parts are both the sworn and unsworn staff who engage in collaborative efforts to serve the community. Capable supervision of these valuable human resources is critical and essential to ensure that the organization meets its strategic objectives in an effective, efficient, ethical, and coordinated manner. Similar to other organizations, this is not a new concept for police agencies.

The direct challenges affiliated with managing employee performance in law enforcement are as predominant now as ever. Nowhere are these tribulations more evident than in the current litigious environment of police labor grievances, accommodations and entitlements, increased public accountability, and fast-tracked promotions. Many law enforcement leaders manage the performance of their employees without difficulty. However, if individuals act inappropriately or do not do their share, the team and the agency’s reputation suffer.

Research indicates the need for leaders to have a deep knowledge base and varied skill sets to effectively lead and manage their organizations.1 Being a police leader requires highly developed management skills; however, sometimes in the quest for leadership, management tools can fall by the wayside.2

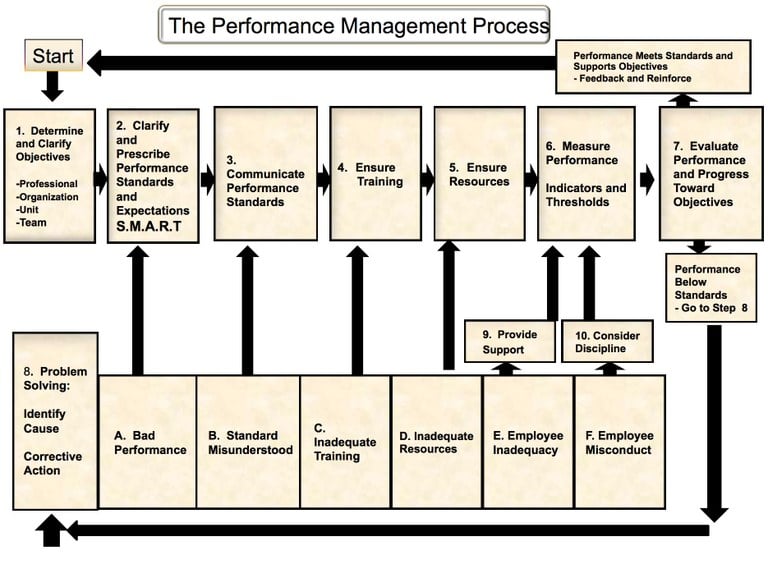

Two instructors in the Toronto Police Service Sergeants Training Course brought their leadership experience to the classroom and translated theory into practice.3 During this course, the instructors distributed a performance management chart (figure 1) they had developed that outlines sequential steps to follow for helping employees improve performance. They based an entire lesson on this chart, which also has been used to counsel employees, connect organizational priorities to employee performance, obtain assistance for troubled staff members, review misconduct cases, implement progressive discipline, testify in arbitrations, and teach managers how to hold employees responsible and accountable for their performance.

Figure 1

Dr. Normore is a program chair and professor at California State University Dominguez Hills, and chief officer of leadership and ethics at the International Academy of Public Safety, Los Angeles, California.

Dr. Ellis is the program head of the Department of Justice Studies at the University of Guelph Humber in Toronto, Ontario, Canada and a retired executive of the Toronto Police Service.

Adapted from Performance Management. Chuck Lawrence and Richard Coulis (1986). Reproduced with Permission.

Step 1: Determine Objectives

The performance management process begins with the supervisor facilitating a discussion regarding the employee’s performance. The supervisor should record this conversation in writing for future review to clarify objectives for employees. An annual evaluation or a concern about an individual’s performance or conduct could initiate this dialogue. At this stage it is important for the employee to understand the professional responsibilities of the position and the legal and moral expectations involved. This discussion also should include a general synopsis of the priorities and goals of the organization, the work unit, and the team, with specific focus on the employee’s role. The supervisor must ensure the employee’s understanding and eliminate any misconception.

Step 2: Clarify Expectations

Once the objectives are presented, the manager must establish the performance standards and expectations. The S.M.A.R.T. (specific, measurable, attainable, reasonable, and timely) goals method is a suitable process to follow to ensure reliability and validity. First, the standards and expectations need to be specific. Next, they must be measurable and demonstrate that they have been met with compliance. The standards have to be attainable and reasonable and consider all factors. Finally, timelines for achievement and measurement must be clarified and well established.

Step 3: Communicate Standards

The third step is one of the most crucial. The supervisor must communicate the standards clearly and make certain that the employee understands in case any future action is necessary for substandard performance. The manager should convey the information verbally and in writing and provide a copy to the employee for reference. Following the S.M.A.R.T. goals method, specific timelines must be established for reviewing the employee’s performance.

Steps 4 and 5: Ensure Resources

When performance standards are set, it is important that the employee is afforded the training, support, and resources necessary to attain them. Sometimes supervisors ask employees to perform tasks that they are not trained to do. In some cases individuals do not have access to the essential equipment, time, or support, which means they do not have the appropriate resources to do the job.

Step 6: Measure Performance

During the performance interview the manager should cover these important steps and address the employee’s concerns. Prior to the review, the supervisor must gather and examine the performance data to determine if the employee has met the standards. The manager should examine carefully all available data in preparation for the next step. Sometimes, when an employee does not meet the standards, the supervisor must investigate any reasons beyond the employee’s control by looking at events during the period that may have hindered performance. All such data are valuable for the performance evaluation meeting.

Step 7: Evaluate Progress

At the performance review meeting, the supervisor evaluates the employee’s measured results against the previously set standards. If the employee meets or exceeds the standards, the meeting is a success. When this occurs performance standards are reset, and the process moves forward starting over at step 1.

If the employee does not meet the standards, the supervisor must begin a formal problem-solving process. If it is determined that noncompliance was beyond the employee’s control, the supervisor should “reset the clock” and reinitiate the performance standards at step 1.

Step 8: Solve Problems

In the problem-solving stage, supervisors sometimes assume that noncompliance is willful, and, thus, employees are subject to disciplinary action. Managers must give careful thought and consideration to the need for such action to avoid potential embarrassment if it is administered unnecessarily. Deciding too quickly may demoralize the employee and cause the team to lose trust in the organization and its leadership. The supervisor must take time to cover several other steps before considering disciplinary sanctions.

If the supervisor determines that there is no justification for poor performance, supervision should be enhanced by resetting the standards and increasing observation of the employee’s activities. This involves returning to step 2 (reiterating the performance standards) and setting new, tighter timelines for compliance. At this stage the manager must identify and record clear consequences for noncompliance and ensure that the employee understands the performance standards. If it is apparent that the standards are misunderstood, the manager must repeat and perfect step 3. It is equally important to reassess the training and resources accessible to the employee to confirm that they are sufficient. Questions regarding whether the employee had adequate instruction and means to do the job arise during discipline and labor hearings. If it is determined that these are lacking, the supervisor must return to steps 4 and 5 to ensure that they are made available.

Step 8 E (employee inadequacy) is an area that is sensitive and often overlooked. Sometimes employees are unable to complete tasks due to lack of personal capacity. After they are hired and have completed their probation, it can be difficult to hold them accountable if it is determined that they do not have the intellectual capacity or physical attributes to meet the standards. During probationary periods, supervisors should employ due diligence and enhanced supervision to ensure that employees can achieve the assigned performance standards.

Other reasons, such as physical or emotional health problems, sometimes cause employees to become inadequate. Supervisors must be sensitive to this possibility, even if the employee is unaware of any health issues. A change in performance without any other explanation may be a clue to an underlying problem. Alcohol or other substance abuse could be the underlying cause of performance noncompliance. Many agencies have employee assistance programs to provide help and support to employees who have such issues. Other situations that cause performance to fall short include such things as severe family stress, workplace bullying, burnout, PTSD, or vicarious trauma. These tribulations, among others, may lead to employee inadequacy that negatively affects work performance.

Step 9: Provide Support

If properly identified and appropriately dealt with, performance issues often can be corrected. In these cases step 9 (provide support) is the logical step for connecting the employee with the appropriate assistance. The supervisor should determine if this is the right action to take.

Step 10: Consider Discipline

When all other steps have been followed, but performance still falls short, the supervisor should consider step 8 F (employee misconduct and discipline). If the supervisor properly communicated the performance standards, supplied training and resources, and provided assistance and support, but poor performance continues, discipline to attempt to correct the behavior is the next step. Disciplinary action should be progressive. If successive attempts to improve performance fail after revisiting the performance management steps, sanctions should increase. This eventually could result in dismissal of the employee. If supervisors and managers have followed all of the steps, the case for severe sanctions is strengthened.

Conclusion

There are 10 steps in the performance management process. Missing any step probably will render any attempts to improve performance unsatisfactory. The authors recommend that managers consistently follow these steps with any working agreements and existing policies. For further reliability, supervisors should use the same performance management process for all employees, and their reports should reflect that they covered all the steps in the performance interview. By having a process to follow, law enforcement supervisors, executives, and governing bodies can ensure that their teams understand the expectations. The process also will provide managers with a foundation for dealing with inadequate performance.

For additional information Dr. Ellis may be contacted at gary.ellis@guelphhumber.ca, and Dr. Normore may be reached at anormore@csudh.edu.

Endnotes

1 Warren G. Bennis and Burt Nanus, Leaders: Strategies for Taking Charge, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: HarperBusiness, 2007); Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap...and Others Don't (New York, NY: HarperBusiness, 2001); Michael Fullan, Leadership and Sustainability: System Thinkers in Action (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2005); and Peter M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Doubleday Publishing, 2006).

2 Jack E. Enter, Challenging the Law Enforcement Organization: Proactive Leadership Strategies (Dacula, GA: Narrow Road Press, 2006); and Mike Wynn, Rising Through the Ranks: Leadership Tools and Techniques for Law Enforcement (New York, NY: Kaplan Publishing, 2008).

3 Richard Coulis and Charles Lawrence, “Performance Management” (presentation, Toronto Police College Supervisors Course, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1986).