Proactive Human Source Development

By Robin K. Dreeke and Kara D. Sidener

For years, many local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies have employed tried-and-true methods for investigating and solving both large and small cases. Most of these approaches relied on identifying human sources and witnesses derived from investigative case information. Law enforcement personnel found these individuals by reacting to this information, as well as by receiving details from Good Samaritans who felt it their civic duty to step forward.

In today’s society and law enforcement climate, investigators need to adapt and update this model. In mainstream investigative work, this methodology remains effective for developing the kind of information needed while reacting to new details gleaned through investigation. But, as law enforcement professionals encounter more complex investigations in the areas of terrorism, cyber crime, and counterintelligence, reacting to new investigative information is simply not good enough. By the time organizations develop the information that may lead to a specific individual, it may be too late. A terrorist attack could have happened, financial losses from a major cyber intrusion may have occurred, or classified national security information may have reached a foreign adversary. The challenge of countering these threats and avoiding the messy cleanup in their aftermath is to proactively develop a confidential human source base to help thwart individuals and groups that do not hold the best interests of the United States or its allies in their thoughts and actions.

Law enforcement training academies and continuing professional development opportunities throughout this nation do an excellent job of emphasizing and teaching the skills needed to both interview and develop a quality human source base identified by solid investigative work. It is widely accepted that no great case will be made without a great human source. However, law enforcement organizations need to shift their focus by emphasizing a more proactive approach to source development. Instead of employing a reactive mentality, they must look for sources of information before crimes occur. This leads to the stressful question for both veteran officers and new hires, “Where do I find a human source without having a crime to tell me where to look?” With seasoned law enforcement professionals in short supply to share this type of knowledge, the authors present one methodology for proactively identifying and finding a confidential human source. Having to get in front of the criminals is not a new problem for law enforcement; rather, the authors offer a refreshing approach to an ever-increasing demand to prevent violence, which—to do so—requires effective human sources.

The Situation

Susan Clark, a seasoned agent, has been assigned to a joint terrorism task force for the past 10 years. During her tenure, she has had some solid successes and is well respected by both peers and managers. Throughout her career, Clark has produced significant results because she paid attention to details and quickly reacted to new information as it developed during the course of her investigations.

Clark’s good friend and partner, Smith, has worked on the squad for many years, even more than she. During their years as partners, Smith taught Clark a great deal about human source development and had become a true master of proactively finding and developing the types of sources and information needed to counter threats to national security. Clark believed that Smith enjoyed a high level of success because of his sincere interest in people and his ability to suppress his ego, two of the strongest attributes of an effective interviewer and source developer.

As one of the leading investigators, Clark was asked to join a new cyber task force her office was forming to better address these issues that crossed multiple criminal and national security programs. Looking for a new challenge, Clark accepted the transfer, thinking that she could aptly adjust her tried-andtrue skills as an investigator to counter the ever-increasing cyber threat. After a few months on the squad, however, she began to feel a bit frustrated. Accustomed to routinely receiving tips or leads from multiple investigative sources, Clark quickly found that this did not occur. As she learned more about cyber threats, she discovered that the perpetrators of these crimes are not particularly obvious.

Hiding in technology can be effective, making it difficult for law enforcement to identify the actual criminals behind the computers. In addition, victims of cyber crimes, whether individuals or corporations, are not as forthcoming as those in other types of crimes. For example, if a major bank discovers a cyber intrusion, even with no apparent crime having occurred, it does not want this to become common knowledge as it could cause clients to lose confidence in the bank’s ability to protect their information. The bank would rather handle the matter internally and avoid any public disclosure. The same holds true not only in the banking industry but also with defense contractors, colleges and universities, private corporations, and nonprofit organizations. To further this problem, even if cyber criminals do not succeed, potential victims may not share how they discovered the efforts of these perpetrators or the activity they have observed and identified by those attempting to compromise their systems.

Special Agent Dreeke serves in the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division.

Special Agent Sidener is assigned to the FBI’s Washington, D.C., office.

What Clark learned from her colleagues with more experience working cyberrelated crimes was that these cases involved more offensive effort than defensive. The key was developing relationships with people who could provide trends and techniques of cyber criminals to proactively educate and inform others to prevent such occurrences. So, Clark had to find a way to get out in front of the cyber criminals.

The Guidance

Feeling somewhat overwhelmed by what she had learned and beginning to miss the days of inherently knowing what to do, Clark realized the value of having worked with Smith for years and decided to talk to him about how she might tackle her new challenge. His approach differed from hers, but because of a common objective, they brought their mutual strengths to a problem and complemented each other. Clark viewed herself as a “by the book” individual who knew the rules and procedures inside and out. Once given a piece of information, no matter how small, she had the tenacity for running it to its logical conclusion and the acumen for piecing all of the elements together to solve a case.

On the other hand, Smith was an “idea guy.” Clark would start briefing him on the details of a case, and immediately all sorts of ideas would pop into his head. A patient person, Smith generally waited until Clark finished and then adeptly added his thoughts about what they should do with the case. His forte included identifying where they might find human sources of information and coming up with how to further their objectives. Not so concerned with the details and administrative requirements for working cases, Smith saw the “big picture.” Clark had taken these natural talents they both had for granted until she found herself without his added skills.

Clark walked down the hall to Smith’s office. Smith turned from his paperwork and said, “Hey, what’s up with you?” Clark bit her lower lip and took a deep breath. Smith offered her the chair he always kept next to his desk for guests. She flopped down with another sigh. Smith commented that he had not seen her look so stressed in many years. Clark explained that she could not get very far on her new squad without first proactively establishing a significant human source base willing to lend a hand. She noted the challenge of the cyber-threat world and how victim companies often are reluctant to come forward. Exasperated, Clark said, “I just need people to tell me what they’re seeing, even if no crime has been committed. How do I find sources with no crime to lead me to them?” Smith just sat and listened in his patient way and kept encouraging her to talk. When she finished, he gave her a lopsided smile and said, “I was worried at first that you had a problem. This is an easy fix for you and me.”

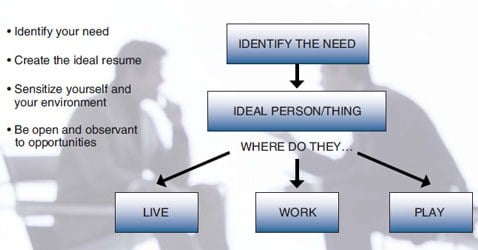

Smith asked Clark if she ever thought about why they were so successful together. She admitted that she had not until she recently remembered his ability to come up with ideas on finding human sources. Smith asked her if she ever considered how he came up with his ideas. She sat back, thought for a moment, and realized that she was starting to piece it together. Clark recalled that she would determine the information they needed based upon the specifics of the case. “Correct,” responded Smith, “then I took the need you identified and created what I thought of as the ideal resume of an individual who would know what you said we needed to find out.” Clark nodded, smiled, and recounted how he had told her to do the same thing when looking for her spouse by creating the ideal resume for someone she thought would be a good match. “The same process works here as well,” said Smith, who then asked what she did next. “Well,” said Clark, “I thought about where that type of person might enjoy socializing or hanging out.” “Excellent,” said Smith, who went on to explain what she knew but had yet to realize. “Once we have the ideal resume of the person we are looking for—that is, the person who can fill a need or information gap—we can start sensitizing ourselves and our environment to our needs and where these individuals may live, work, and play.”

Clark asked, “What do you mean by ‘sensitizing’?” Smith replied, “You recently purchased a new car, didn’t you?” Clark furrowed her brow and gave Smith an inquisitive look as she responded, “Yes, so?” Smith commented that it involves the same process. Smith took out a piece of paper and drew a pyramid-shaped flow chart (figure 1). At the top, he wrote the words identify the need inside a rectangular box. He then drew an arrow straight down to a second rectangular box where he wrote the words ideal person/thing inside. Smith paused and said, “What kind of car did you decide to purchase?” Clark named the make and model and Smith asked, “Why that car?” Clark replied that it had the proper amount of space she needed for her family, good fuel economy, and high safety ratings. Smith stated, “You just identified your need and then the ideal thing to fit that need.” Smith referred Clark to boxes one and two on his diagram. Smith asked what she did next. Clark explained that she had looked in classified ads and told her friends and family about the kind of car she wanted. Smith said, “Great, what you began doing was sensitizing yourself and your environment to your need. Did you start seeing that make and model of vehicle everywhere?” Clark responded that she had and that it seemed strange. Smith pointed out that it was not because a lot of people had suddenly purchased the same vehicle but because Clark had sensitized herself to her designated need and started to immediately recognize opportunities. Smith continued, “You then expanded your sensitizing by letting your friends and family know of your identified need.” Smith explained that by sensitizing her friends and family, they, in turn, started recognizing opportunities for her as well. He advised that this was exactly what they had done together when working on the terrorism task force. Clark would identify the need, and Smith would proactively find a source who could fill it.

“Smith reminded Clark of the types of human sources they had developed in the past and how most of the time, they would sit for hours listening to these individuals talk about the concerns and issues in their own lives.”

Smith said that they would tackle her challenge using the same model after she explained how she eventually found the vehicle. Clark said, “A friend who I had told about the type of vehicle I wanted informed me that her neighbor was selling one.” Clark elaborated, “I was so happy and thankful that my friend had found the car for me that I sent her a nice gift basket.” Smith commented, “You naturally did one of the most important things we need to do in any relationship: give when receiving.” He explained that solid relationships will continue to grow when a quality exchange of giving and receiving by both parties takes place. This concept is not limited to material items. In fact, in most cases, giving and receiving often involves just our time and listening to one another. Smith reminded Clark of the types of human sources they had developed in the past and how most of the time, they would sit for hours listening to these individuals talk about the concerns and issues in their own lives. Clark said that she remembered all too well how they had listened to one excellent source talk for over 3 hours about the problems at his work when all they needed from him took only 10 minutes to find out.

The Solution

Smith nodded his head, remembering that particular meeting, and said, “Now that we have our model started, let’s take a look at your situation and start applying it to your new challenge. What type of information do you need in your investigations to be proactive?” Clark began, “I need an individual who sees the type of activity that indicates someone trying to get access to a network, even if that person doesn’t have a specific crime to report. Someone like a network security administrator who not only has the technical know-how but also the access to describe the kind of activity. Someone who could say, ‘Yeah, last week someone attempted to hack into our network, and this is how they tried to do it.’ Perhaps even someone who is active in Web chatting or blogging, following different types of groups that may proactively share this kind of information with each other.” “Excellent,” Smith commented, “now that we know what you need, let’s create an ideal resume of the type of person who can give us that type of information.” Clark replied, “That’s easy, obviously someone in the IT industry who, perhaps, came in without a 4-year degree and got it later after gaining job experience and various computer certifications. I would bet someone who has spent time gaming, too. A network or systems administrator with management and security experience and access who could speak more openly with me than those not in a management position.” Smith quickly smiled before Clark even finished. She asked, “Why are you smiling at me?” Smith said, “I have someone for you to meet.”

Smith described his casual conversation with the person seated next to him on a recent plane trip. He explained that even though he often finds it exhausting, given that he is in the business of working with people, he always attempts to speak with individuals he encounters, make a favorable impression, and find out a little bit about them and where they work. Smith did not need to remind Clark of their motto, “Assess everyone you meet in your life as a potential source.” Smith described the woman he had met on the plane, explaining her personality and what he assessed as her preferred communication style and sharing some details about where she grew up, her family situation, and other identifying personal information he had elicited during the conversation.1 Clark asked, “Great, how does that help me?” Smith smiled as he said, “She is the network administrator for a major defense contractor right here in our city.” Smith gave Clark the woman’s business card, explaining that at the end of their flight, he had told the woman about his line of work and she, in turn, had said that she had really enjoyed chatting with him. Then, she had stated that if he ever needed anything, just call or e-mail her. Smith then asked Clark, “So, what do you think just happened?” She replied that by identifying her need and sensitizing her environment to that need (i.e., telling Smith the kind of source and information she needed and, in the process, externalizing her need and and expanding the sensitized environment), she had produced a result.

“She replied that by identifying her need and sensitizing her environment to that need (i.e., telling Smith the kind of source and information she needed and, in the process, externalizing her need and and expanding the sensitized environment), she had produced a result.”

Although extremely appreciative for the great start Smith had given her, Clark realized that she definitely needed a few more leads to start making a dent in her work. Smith said, “After we have sensitized our environment, we need to take a few more proactive steps to increase our chances of success. In this next step, we will come up with ideas about where this ideal person/thing might live, work, and play. Once we have identified some possible locations, we again will sensitize our environment in those types of venues. For example, let’s go back to your car purchase. You sensitized your environment and your friend came up with your solution. What would you have done next if your friend hadn’t found someone selling the car you wanted?” Clark thought for a minute and said she would have identified some car dealerships selling that type of car. “That’s exactly right,” exclaimed Smith. He added that a few years back when he was car shopping, he had done exactly that: selected the type of vehicle, identified some car dealerships, and sensitized a few salesmen to his needs. Within days, he had multiple calls and offers. “In other words,” said Smith, “I went to where my ideal thing might live or work and sensitized the environment.”

Smith turned the conversation back to Clark’s issue and said, “Now that we have identified the ideal type of person, let’s focus on where that person might work and play.” Smith asked Clark to think about what types of groups, organizations, and clubs the individuals she was looking for would belong. Clark sat silently for a moment as she thought through her mental lists and came up with a quick match. “InfraGard meetings,” she exclaimed.2 “Perfect,” said Smith. Clark said that she would attend an upcoming meeting the following week and try to sensitize the environment to her need. “That sounds like a great place to start,” said Smith.Clark thanked Smith for taking time with her and asked him if he had any last thoughts. Smith took out a worn 3” x 5” card from his wallet. Clark immediately recognized it as the one he looked at prior to every source meeting that the two had conducted. Smith stated, “I know you know the stages of the relationship-building process, but it’s always good to remind ourselves of these ideals before we converse with the individuals we need to help

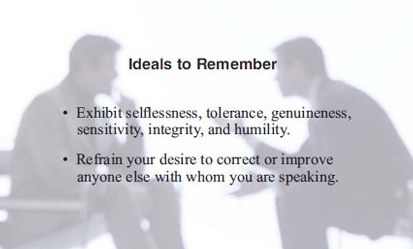

Clark thanked Smith for taking time with her and asked him if he had any last thoughts. Smith took out a worn 3” x 5” card from his wallet. Clark immediately recognized it as the one he looked at prior to every source meeting that the two had conducted. Smith stated, “I know you know the stages of the relationship-building process, but it’s always good to remind ourselves of these ideals before we converse with the individuals we need to help us.”3 Smith then read the words selflessness, tolerance, genuineness, sensitivity, integrity, and humility and the phrase refrain your desire to correct or improve anyone else with whom you are speaking from his worn card. Clark thanked Smith for the insights and the fun of working together again and went off with renewed energy.

The Result

A few weeks later, Smith took a break from his work and strolled down the hall to Clark’s office. He had not seen her since their last conversation and was curious about how she was doing. She was not at her desk, but it was piled with a stack of newly opened files, scribbled with notes, that exuded an overall sense of organized chaos that he had seen in their years of working together when cases were going well.

Smith looked up to see Clark briskly walking down the aisle toward her desk with a broad smile. She greeted Smith and stated, “Simple genius.” “Huh?” responded Smith. Clark quickly commented that all of the things they had talked about were common sense but seemed like a mystery until thinking about them and writing them down. Clark described how she went to the InfraGard meeting and made a few friends. A week later, she received several leads and ideas from these people and many others willing to help. She said, “I now have more work than I know what to do with. I just finished speaking with our management regarding more resources for our ever-increasing workload.” “Congratulations,” said Smith with a wry grin, “be careful what you wish for, you might just get it.”

Conclusion

While leveraging collective strengths is an obvious benefit of teamwork, being able to adapt that symbiotic relationship to different, ever-changing challenges is a talent that the law enforcement community has embraced. As law enforcement professionals, we need to continue our efforts in proactively developing human sources who can provide us with the types of information that will allow us to combat crime, of any nature, before criminals have the opportunity to act.

The methodology of identifying a need, sensitizing the environment, and then externalizing that need to others, along with expanding the environment in which we look for an answer to the need, is one of many ways we can proactively identify people who can help us before crimes occur. It helps to articulate the need and go through the steps of who would be the ideal person to provide the information to fill that need and then go about finding that person in a variety of environments (i.e., where they live, work, and play). In today’s ever-changing and challenging environment, it is important for law enforcement to employ as many tools as possible to stay ahead of the criminals.

Readers interested in discussing this topic can contact Special Agent Dreeke at Robin.Dreeke@ic.fbi.gov or Special Agent Sidener at Kara.Sidener@ic.fbi.gov.

Endnotes

1 Robin K. Dreeke and Joe Navarro, “Behavioral Mirroring in Interviewing,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, December 2009, 1-10.

2 InfraGard is an association of businesses, academic institutions, law enforcement agencies, and other participants dedicated to sharing information and intelligence to prevent hostile acts against the United States. Its website is http://www.infragard.net.

3 Robin K. Dreeke, “It’s All About Them: Tools and Techniques for Interviewing and Human Source Development,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, June 2009, 1-9.