Reading People: Behavioral Anomalies and Investigative Interviewing

By David Matsumoto, Ph.D., Lisa G. Skinner, J.D., and Hyisung C. Hwang, Ph.D.

While interviewing a crime suspect a police officer asks what happened. For an instant the interviewee’s eyes get wide so that the white above the irises is visible. The suspect’s story begins with details about memories from before the incident, including things the alleged offender did and did not do. The suspected criminal describes the event while wringing the hands and looking away, up and to the left, not making direct eye contact. The interviewee’s speech becomes slower and references to other people change with the use of pronouns. The suspect, whose left eyebrow is twitching, does not speak about the incident itself and finishes the story with “and that's about it.”

The description above makes much of this individual’s story suspicious from a credibility assessment standpoint. However, when conducting interviews, investigators must ask themselves some important questions based on their observation of behavioral anomalies.

- What cues contribute to the determination, and why?

- Which behaviors are meaningful signs, and which are not?

- Which actions are true signals of something important, and which are just noise?

- Which signs provide guidelines for further probing and questioning?

- What insights can be gained from the observed indicators, and why?

Indicators

Many law enforcement professionals understand and appreciate the importance of behavioral anomalies. These verbal and nonverbal signs of cognitions and emotions provide additional clues to what an individual is thinking and feeling beyond the content of the words being spoken. In the context of investigative interviewing, these behavioral anomalies are called indicators.

These anomalies provide important cues and valuable insight into the personality, motivation, and intention of suspects. They can be signs of hostile intent, suspicious behavior, veracity or lying, or topics and concerns that are important to the interviewee. These crucial bits of knowledge give investigators information superiority that can guide them through the process and help them complete interviews. Individuals typically do not know that they are revealing these indicators.

Dr. Matsumoto is a professor of psychology at San Francisco State University and director of a private training and consulting firm in California.

Ms. Skinner is a retired FBI Supervisory Special Agent and former instructor at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia.

Dr. Hwang is a research scientist and vice president of a private training and consulting firm in California.

When reading people, one important distinction interviewers must make is the difference between validated and nonvalidated indicators. Those that are validated have scientific and field evidence documenting the association between the behavior and specific cognitions or emotions. These anomalies are laboratory tested under strict scientific conditions and vetted in the field by practitioners. Nonvalidated indicators lack such data—either in scientific evidence, field operations, or both.1

Validation provides evidence for accuracy and consistency across various people in different contexts. Noticing that a suspect’s hands were held in a certain way when describing an incident that later turned out to be a lie is not evidence that the behavior is indicative of lying for other people in varying situations. Observation alone is not sufficient to label a certain behavior as a validated indicator because it has not withstood the scrutiny of rigorous testing in the laboratory and the field. Such testing would require establishing the conditions in which the indicator may or may not occur with multiple people. If the behavior ensued that would be evidence for its validation, and if it did not that would be verification for its nonvalidation.

There are validated and nonvalidated indicators imbedded in the example at the beginning of this article. The flash of the eyes so that the white above the iris is seen is a validated indicator of concealed fear, and the suspect’s comments about behavior that did not occur are indicative of a potential lie. Looking up to the left and twitching of the left eyebrow are not validated indicators of lying, even though many people believe they are.

Programs that teach nonvalidated indicators produce negative results in people’s ability to detect lies from truths.2 For example, a common belief is that a lack of eye contact is an indicator of lying; however, numerous studies have tested this and most do not support it. Therefore, this belief is more myth than reality.3 A recent study showed that liars know this too and compensate for it by looking the interviewer straight in the eye more than truth tellers.4

Categories

There are two categories of validated behavioral indicators that are relevant to interrogations. One involves linguistic markers used in words when individuals provide statements or answer questions. This category is entirely verbal—based on principles of human memory and recall—and suggests that lies are different from truths in their demands upon memory, which is reflected by changes in grammar and language. Research has indicated that lies comprise fewer words and more omissions of information; are less plausible, structured, and logical; are more discrepant and ambivalent; contain repeated details; lack contextual imbedding; and include more descriptions of what did not occur.5 These findings lead to specific linguistic and grammatical indicators of veracity and lying—such as the use of negation, extraneous information, and different types of adverbs—that may be identified in statements and interviews.

The second category includes nonverbal behaviors (NVB). Research has shown that various emotions and cognitions are communicated through facial expression, voice tone, gesture, body movement, and posture.6 In the investigative context, NVB indicators occur because conflicting thoughts and feelings transpire when people lie and are under stress but attempt to hide their feelings and expressions. These anomalies often leak out nonverbally. Research has established that NVB indicators of lying include changes in the use of speech illustrators and symbolic gestures; subtle and microfacial manifestations of facial expressions; variations in blinking, pauses, and speech rates; and outward attempts to regulate emotions.7

It is possible to train individuals to identify verbal and nonverbal indicators of truthfulness and lying. Verbal indicators are acknowledged through analysis of specific linguistic markers and words using Statement Analysis (SA)—also known as Statement Validity Analysis, Criteria-Based Content Analysis, Reality Monitoring, and Scientific Content Analysis.8 Nonverbal indicators are identified as subtle or microfacial expressions of emotion, gestures, vocal changes, and body language.9

Real-Life

Statement and nonverbal analysis are not new to law enforcement as the techniques have been taught to investigators for years. However, in real-life, indicators of veracity and lying occur simultaneously, and awareness of both increases an investigator’s ability to identify meaningful content areas of an interview; detect clues to deceit; and provide additional insight into the thoughts, feelings, personality, and motivation of the interviewee. People sometimes produce verbal indicators with no NVB and NVB indicators without talking. Investigators who pay attention solely to one or the other may miss valuable information.

The importance of considering verbal and nonverbal indicators concurrently was highlighted in a recent study—published in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin—that examined the combined contributions to the prediction of deception or truthfulness.10 The study showed that members of ideologically-motivated groups committed one of two types of lies. In one, participants were placed in a situation where they could commit a crime—steal $50 in cash from a briefcase—and later were interviewed about whether they carried out the crime or not (the crime scenario). In another setting, individuals chose to lie or tell the truth about their beliefs concerning their political cause (the opinion scenario). Regardless of the circumstances, there were stakes involved—if they were judged as lying, they would lose their participation fee and face one hour of white noise blasts while sitting on a cold, steel chair in a small, cramped room.

Videos of 20 individuals—10 each from the crime and opinion scenarios, half truth tellers and half liars—were analyzed. Analyses of their words and NVB together led to a 90 percent accuracy rate for classifying the individuals as lying or telling the truth. Compared to the average accuracy rate of 53 percent—no better than chance—by observers in previous studies, the findings indicated that behavioral anomalies in verbal statements and NVB collectively provided a better source for determining veracity and deceit than basic observation.11

Example

Investigators gained valuable information within 40 seconds of an interview with a 42-year-old female suspect who allegedly assaulted a minor. After officers Mirandized and obtained background information from the suspected perpetrator the discussion ensued—nonverbal behaviors are italicized.

The investigator asked, “Mary, do you know the reason why you’re here today?”

Mary replied, “I have no idea.” She smiled, leaned forward, and showed concern on her face. Her voice sounded vulnerable.

The investigator said, “Okay…the reason why you’re here today is that an allegation has been made on you…”

Mary responded, “Okay.” She spoke softly while nodding her head.

The investigator continued, “…that you assaulted Joe.”

Mary’s brows went up and her eyes opened wide so that the whites above the eyes could be seen. Her jaw dropped and her mouth opened.

The investigator asked, “Do you know who Joe is?”

Mary replied, “I have no idea.” She shook her head quickly and gave a brief microfacial expression of disgust.

The investigator said, “Joe lives down the street from you.”

Mary (displaying another microfacial expression of disgust) asked, “What?” She spoke incredulously, leaned forward, and smiled.

The investigator inquired, “An allegation came out that you assaulted him. He’s 13 years old. I’m just going to point blank ask you, did you have anything to do with it?”

Mary (smiling) responded, “No. He was definitely hitting on…. It was one night when they spent the night over (smiling) and he was acting kind of strange that night and nothing happened.”

At the beginning when Mary was asked if she knew why she was in the interview, Mary smiled, leaned forward, looked concerned, and said in a vulnerable voice, “I have no idea.” Her coy, almost flirtatious demeanor suggested that this may be a major characteristic of her personality. Mary said “Okay” when the investigator stated that an allegation had been made about her. This implied that she knew what the investigator was talking about and could speak to her participation in the incident. It also could have indicated that Mary merely was tracking the conversation by acknowledging what was being said—known as back-channel communication. Knowing her baseline would help the investigator make this distinction.

Mary’s eyes widening for an instant indicated fear, suggesting that she was afraid of something but trying to control her outward display—as opposed to someone who was innocent but afraid of being misbelieved, in which case the fear would not be displayed as a microexpression. When Mary said that she had no idea who Joe was but exhibited two microexpressions of disgust, this suggested that she knew exactly who Joe was—part of her brain was processing information that was incongruent with what she was saying. She then revealed that she did know Joe, despite having just denied it, by stating, “He was definitely hitting on…” before she stopped herself. Mary saying “It was one night…” indicated that this was an incident she knew about. When Mary tried to stop the conversation by saying that “nothing happened” this signified that something actually had happened, but she was omitting the facts.

This example demonstrates how verbal and nonverbal indicators of veracity and deceit occur simultaneously during communication. They are woven into the ongoing interaction and convey a wealth of information above and beyond the surface meaning of the words. It would benefit officers to identify these indicators when conducting interviews. Their detection provides valuable assistance for guiding the investigator to meaningful content areas, helping build cases strategically and tactically, developing themes for use in interrogations, and arriving at ground truth quickly and accurately.

Training

The techniques for both statement and NVB analysis typically have been taught separately to law enforcement officers, providing them with increased skill in one particular technique but resulting in their missing much of the useful information that interviewees impart. A few years ago the FBI National Academy (NA) began offering a course on investigative interviewing that united the techniques of statement and NVB analysis. Merging these techniques into a single application was a risk; however, it was possible that training in both could produce an information overload such that their practical application would have been unsuccessful. Trainees learning both techniques independently often reported that they were overwhelmed by the amount of detail to which they had to attend. Fortunately, combining the techniques produced positive results and the benefit of more real-life circumstances.

Mid-to-upper-level career law enforcement officers concurrently enrolled in two courses—one was a traditional course on statement analysis (trainees had to learn the basics of SA) and the other was a combined SA and NVB analysis course. Both courses covered validated indicators of truthfulness and lying culled from research and included lectures, discussions, video reviews, group projects, and individual practicum. After learning the basic principles of both statement and NVB analysis, trainees practiced on realistic source materials—actual statements and videos of suspects, witnesses, and informants telling truths and lies—to hone their skills. The combined course also required trainees to learn how to recognize microfacial expressions of emotion.

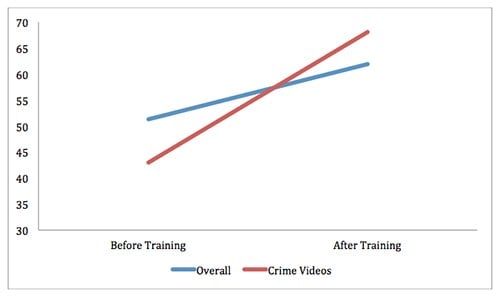

By the end of the courses, trainees had improved their capacity to recognize verbal and nonverbal indicators of veracity and deceit and to incorporate those skills into their interview strategies. Pre- and post-test data on their ability to detect truths from a standardized set of videos were obtained in three sessions. At the beginning of the courses, attendees viewed a set of 10 videos prior to any training in SA or NVB analysis. Participants watched a different set of 10 videos at the end of the courses. The videos were switched across both courses so that any findings were not specific to one set. A sizable increase in accuracy rates—between 10 and 25 percent—in the trainees’ ability to detect lies from truths resulted (Figure 1). These improvement rates were remarkable since the test videos lasted only 60 to 90 seconds. If the trainees had been able to question the interviewees in person, in a longer interview, with other typically available sources of evidence—forensics, witness statements, and physical evidence—the increase could have led to substantial differences in the efficacy by which investigators obtain ground truth and close cases.

Figure 1 - Accuracy Rates Before and After Training, Separately for All Videos and Crime Videos Only

Although trainees initially reported being overwhelmed by the details, they expressed greater comfort with the techniques by the end of the sessions. Many students reported that after learning and applying both statement and nonverbal behavior analysis they recognized so many indicators that too many potential clues providing insight into interviewees’ minds became apparent. They had to prioritize and determine which ones to act on, thereby producing the collateral benefit of improving their thinking about interrogation strategies and tactics.

Conclusion

Behavioral anomalies—the verbal and nonverbal indicators of veracity and deceit—occur simultaneously in real-life. Recognizing these indicators helps investigators detect lies and gain insight into the personality, motivation, and internal conflicts of interviewees and identify content areas necessitating further exploration and discovery. Law enforcement officers must imbed these techniques within their strategic interview methodology.

Behavioral anomalies are signs investigators can use to determine truth; however, they should not be interpreted strictly given that research has not identified any behavior or behavior combinations that are unique to lying.12 They are highly dependent upon the interviewer’s skills and should be used strictly as a means to an end.

Using behavioral anomalies in investigative interviewing will not solve every case. Interviews should be augmented by witness statements, forensics, and other evidence. Investigators must prepare and plan for interviews, develop questions, and guide discussions as they recognize indicators. Those who have lie detection training must be cautious of post-training biases.13 However, identifying valid indicators—both verbal and nonverbal—remains a useful tool for any law enforcement investigator.

Additional information may be obtained from the authors at dmatsumoto@humintell.com, hshwang@humintell.com, or lisaglennskinner@gmail.com.

Endnotes

1 There are different types of nonvalidated indicators. For example, potential indicators that have never been tested scientifically should be considered unvalidated indicators. Potential indicators that have been tested scientifically but did not produce reliable findings would be considered invalidated indicators. For the purposes of this article, both are called nonvalidated indicators.

2 S.M. Kassin and C.T. Fong, "I'm Innocent: Effects of Training on Judgments of Truth and Deception in the Interrogation Room,” Law and Human Behavior 23, no. 5 (1999): 499-516; and N. Smith, Reading Between the Lines: An Evaluation of the Scientific Content Analysis Technique (SCAN) (London, UK: Police Research Series, Policing and Reducing Crime Unit, 2001), http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.114.2971&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed December 5, 2013).

3 The Global Deception Research Team, “A World of Lies,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 37, no. 1 (January 2006): 60-74; and M.G. Frank and E. Svetieva, “Deception,” in Nonverbal Communication: Science and Applications, ed. D. Matsumoto, M.G. Frank, and H.S. Hwang (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2013), 121-144.

4 S. Mann, A. Vrij, S. Leal, P.A. Granhag, L. Warmelink, and D. Forrester, “Windows to the Soul? Deliberate Eye Contact as a Cue to Deceit,” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 36, no. 3 (September 2012): 205-215.

5 B.M. DePaulo, J.J. Lindsay, B.E. Malone, L. Muhlenbruck, K. Chalrton, and H. Cooper, “Cues to Deception,” Psychological Bulletin 129 no. 1 (2003): 74-118; N.D. Duran, C. Hall, P.M. McCarthy, and D.S. McNamara, “The Linguistic Correlates of Conversational Deception: Comparing Natural Language Processing Technologies,” Applied Psycholinguistics 31, no. 3 (July 2010): 439-462; M.L. Newman, J.W. Pennebaker, D.S. Berry, and J.M. Richards, “Lying Words: Predicting Deception from Linguistic Styles,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29, no. 5 (May 2003): 665-675; S. Porter, A.R. Birt, J.C. Yuille, and D.R. Lehman, “Negotiating False Memories: Interviewer and Rememberer Characteristics Relate to Memory Distortion,” Psychological Science 11, no. 6 (November 2000): 507-510; S. Porter and L. ten Brinke, “The Truth About Lies: What Works in Detecting High-stakes Deception?” Legal and Criminological Psychology 15, no. 1 (February 2010): 57-75; and A. Vrij, “Criteria-Based Content Analysis: A Qualitative Review of the First 37 Studies,” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 11, no. 1 (2005): 3-41.

6 D. Matsumoto, M.G. Frank, and H.S. Hwang, eds., Nonverbal Communication: Science and Applications (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012).

7 B.M. DePaulo, J.J. Lindsay, B.E. Malone, L. Muhlenbruck, K. Chalrton, and H. Cooper, “Cues to Deception,” 74-118; C.M. Hurley and M.G. Frank, “Executing Facial Control During Deception Situations,” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 35, no. 2 (June 2011): 119-131; S. Porter and L. ten Brinke, “Reading Between the Lies: Identifying Concealed and Falsified Emotions in Universal Facial Expressions,” Psychological Science 19 (2008): 508-514; S. Porter and L. ten Brinke, “The Truth About Lies: What Works in Detecting High-stakes Deception?” 57-75; S. Porter, L. ten Brinke, and B. Wallace, “Secrets and Lies: Involuntary Leakage in Deceptive Facial Expressions as a Function of Emotional Intensity,” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 36, no. 1 (March 2012): 23-37; L. ten Brinke, S. Porter, and A. Baker, “Darwin the Detective: Observable Facial Muscle Contractions Reveal Emotional High-stakes Lies,” Evolution and Human Behavior 33, no. 4 (July 2012): 411-416; and G. Warren, E. Schertler, and P. Bull, “Detecting Deception from Emotional and Unemotional Cues,” Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 33, no. 1 (March 2009): 59-69.

8 U. Undeutsch, “The Development of Statement Reality Analysis,” in Credibility Assessment ed. J.C. Yuille (Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic, 1989), 101-119.

9 D. Matsumoto and H.C. Hwang, “Evidence for Training the Ability to Read Microexpressions of Emotion,” Motivation and Emotion 35, no. 2 (April 2012): 181-191; and D. Matsumoto and H.C. Hwang, “Judgments of Subtle Facial Expressions of Emotion” (forthcoming).

10 D. Matsumoto, H.C. Hwang, L. Skinner, and M.G. Frank, “Evaluating Truthfulness and Detecting Deception,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin (June 2011): 1-8.

11 C.F. Bond and B.M. DePaulo, “Accuracy of Deception Judgments,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10, no. 3 (August 2006): 214-234.

12 M. Zuckerman, B.M. DePaulo, and R. Rosenthal, “Verbal and Nonverbal Communication of Deception,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 14, ed. L. Berkowitz (New York, NY: Academic Press, 1981), 1-59.

13 J. Masip, S.L. Sporer, E. Garrido, and C. Herrero, “The Detection of Deception With the Reality Monitoring Approach: A Review of the Empirical Evidence,” Psychology, Crime, and Law 11, no. 1 (2005): 99-122.

“Investigators must ask themselves some important questions based on their observation of behavioral anomalies.”