Saving One Overdose Victim at a Time

By Patrick Gallagher, M.P.A.

In the United States, drug overdoses cause more deaths than do gunshots or automobile crashes.1 Every day, over 115 such instances involve opioids—including legally obtained substances—alone.2 This epidemic touches all classes of people.

The Virginia Beach, Virginia, Police Department (VBPD) has seen a recent increase in opioid overdoses and related deaths among people in its jurisdiction. In response, the agency has equipped officers with the rescue drug naloxone and educated them on how to initiate lifesaving measures. This effort has spared the lives of many victims and hopefully put them on the path to recovery.

Problem

This issue relates not only to the use of illegal opioids, such as heroin, but also the abuse of prescription drugs. Many people become addicted to opioid-based medications, such as oxycodone, given by doctors for pain management. In fact, in no other nation do persons consume more of these drugs.3

Addicts often find that despite developing their habit while under a doctor’s care, they have the same potential for death as persons enslaved through poor life choices. Perhaps some pharmaceutical advertisements contribute to the problem by minimizing risks.

Deputy Chief Gallagher serves with the Virginia Beach, Virginia, Police Department.

These legal drugs have transitioned into the black market. To make matters worse, fentanyl—a synthetic opioid pain medication—has become the primary choice for many addicts.4 Cheaper and easier to make than heroin, it is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine.5

Persons addicted to opioids continually search for their next “fix.” They may exhibit physical changes, such as sunken eyes, rotting teeth, and a pale complexion. Other signs may include aggression, clumsiness, decreased empathy, lack of self-control, impaired cognitive function, inability to effectively communicate, and loss of dignity.6

The outcome is predictable and the results tragic. Sometimes, death occurs, whether by suicide, accidental overdose, or homicide by another addict.

Indeed, these individuals may engage in violent and murderous behavior. For example, one oxycodone addict killed a Virginia Beach pharmacist. Afterward, he drove to another pharmacy and robbed employees at gunpoint to obtain painkilling drugs. The subject then led police on a high-speed chase and shot at several officers prior to his arrest. He later was convicted and sentenced to life plus 48 years in prison.7

Initiative

Solutions to this epidemic will not come from the criminal justice system. Police departments, courts, and correctional facilities cannot solve the problems of drug abuse and addiction, nor can they impact the conditions that create these issues.

Social or criminal sanctions will not deter addicts. These individuals do not fear arrest or incarceration; they only feel pain as a result of their dependency.

Addicts constantly ingest variations of what they think is the same drug. Further, if they cannot obtain what they feel they need, these persons may choose to experiment with something new. They have limited options for feeding their addiction. When seeking that high, addicts recognize the inherent risks. The margin of error depends on potency and quality of the drug, user tolerance, and availability of needed medical treatment.

“This effort has spared the lives of many victims and hopefully put them on the path to recovery.”

9hile law enforcement cannot solve the addiction epidemic as a whole, it can impact the last criteria. To this end, in March 2016, VBPD became the first police agency in the state to deploy the naloxone antidote to counter potentially deadly opioid overdoses.8 The department has become a partner in the local emergency medical strategy to address the area’s increase in opioid overdoses.

VBPD developed a plan to provide the necessary training to its officers and to deploy naloxone in ample amounts throughout the city’s four precincts. Officers carry or have access to the antidote while on patrol, thus reducing the time delay in administering medical care. Providing naloxone to the addict in a timely manner literally can mean the difference between life and death.9 Police often respond first to such incidents and can initiate lifesaving efforts quickly.

The drug itself costs VBPD approximately $53 per unit—far less than the value of a human life. For an agency of its size, 500 antidote units cost over $26,000.

Many agencies do not allow their officers to administer the medication because of potential liability. However, as of 2016, over 40 states have passed laws shielding individuals who deploy naloxone to apparent overdose victims.10 Further, police departments in New York, Massachusetts, and other locations have begun equipping officers with the antidote and have seen success with the practice.11

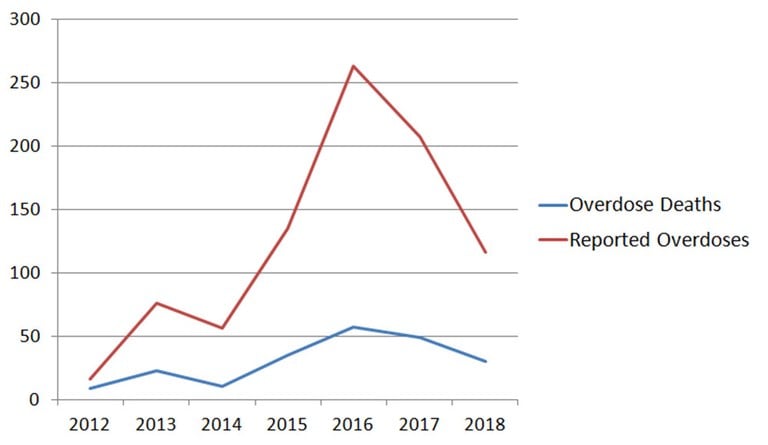

Virginia Beach opioid deaths rose to 57 in 2016, up from 9 in 2012. In 2017—the first full year in which officers carried naloxone—the number of opioid-related deaths decreased to 49. During 2018, 30 fatalities occurred.12

Opioid Overdoses and Deaths

“Addicts often find that despite developing their habit while under a doctor’s care, they have the same potential for death as persons enslaved through poor life choices.”

Source: Virginia Beach, Virginia, Police Department

So far, VBPD has administered the drug over 100 times before emergency personnel arrived on scene. Without the antidote, many of the victims would have died. Fortunately, citizens in Virginia have received access to the medication (other states have instituted similar policies), and they also play an important role in helping to save lives.13

Law Enforcement Naloxone Toolkit

The U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, offers a one-stop clearinghouse of information and resources for state, local, and tribal law enforcement entities interested in establishing a naloxone program. It gives officers and their agencies the knowledge and tools they need to prevent overdose incidents from becoming fatalities before emergency medical personnel arrive.

Eighty resources from 30 contributing law enforcement and public health organizations include data collection forms, standard operating procedures, officer training guides, community outreach materials, and memoranda of agreement. All can be downloaded and customized. Police agencies also can request technical assistance to help them implement or enhance a naloxone program.

This toolkit is available at https://www.bja.gov/justicetoday/1_21_2015.html.

Conclusion

Of course, the Virginia Beach Police Department’s naloxone program does not solve the larger problem of addiction. However, the agency has found success in each application of the antidote, and it hopes that each revival will lead to treatment, one addict at a time. Other agencies should take the bold step and follow this practice.

“So far, VBPD has administered the drug over 100 times before emergency personnel arrived on scene.”

Deputy Chief Gallagher can be reached at pgallagh@vbgov.com.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Drug Overdoses Kill More Than Cars, Guns, and Falling, September 2014, accessed July 27, 2018, https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/drug-overdoses-kill-more-than-cars-guns-falling.

2 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Understanding the Epidemic, August 30, 2017, accessed July 27, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html.

3 America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse, Senate Caucus on International Drug Control, May 14, 2014, accessed July 27, 2018, https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2018/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse.

4 Josh Katz, “Drug Deaths in America Are Rising Faster Than Ever,” New York Times, June 5, 2017, accessed July 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/06/05/upshot/opioid-epidemic-drug-overdose-deaths-are-rising-faster-than-ever.html?_r=0.

5 Everett Stephens, “Opioid Toxicity,” Medscape, October 6, 2017, accessed July 27, 2018, http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/815784-overview.

6 “54 Heroin Abuse or Addiction Warning Signs,” New Hope Recovery Center, accessed July 30, 2018, http://www.new-hope-recovery.com/center/2013/08/08/heroin-abuse-warning-signs/; and “Opioid Addiction Signs, Effects, and Symptoms,” Acadiana Addiction Center, accessed July 30, 2018, https://www.acadianaaddiction.com/addiction/opioids/symptoms-signs-effects/.

7 John Holland, “Va. Beach Robbery Suspect Id’d, Charged with Murder,” Virginian-Pilot (Norfolk), April 15, 2014, accessed July 30, 2018, https://pilotonline.com/news/local/crime/article_05706dad-d449-50e6-af08-880f31f28000.html; and Elisabeth Hulette, “Beach Pharmacist Killer Gets Life Plus 48 Years in Prison,” Virginian-Pilot (Norfolk), May 28, 2015, accessed July 30, 2018, https://pilotonline.com/news/local/crime/beach-pharmacist-killer-gets-life-plus-years-in-prison/article_4f20f84f-81ed-507f-89b3-b1ff6712b7a0.html.

8 Jane Harper, “In Just 6 Months, Virginia Beach Police Have Stopped 30 Heroin Overdoses by Carrying Drug,” Virginian-Pilot (Norfolk), October 1, 2016, accessed July 30, 2018, https://pilotonline.com/news/local/health/in-just-months-virginia-beach-police-have-stopped-heroin-overdoses/article_cc52daa9-0213-5021-b6a9-782d1f12f513.html.

9 Katharine Q. Seelye, “Naloxone Saves Lives, but Is No Cure in Heroin Epidemic,” New York Times, July 27, 2016, accessed July 30, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/28/us/naloxone-eases-pain-of-heroin-epidemic-but-not-without-consequences.html?_r=0.

10 “U.S. Map for Naloxone Administration Laws and The Good Samaritan Law,” Chooper’s Guide, accessed July 30, 2018, http://choopersguide.com/content/naloxone-laws-by-state-map.html#Virginia_Naloxone_Laws.

11 Corey S. Davis, Sarah Ruiz, Patrick Glynn, Gerald Picariello, and Alexander Y. Walley, “Expanded Access to Naloxone Among Firefighters, Police Officers, and Emergency Medical Technicians in Massachusetts,” American Journal of Public Health 104, no. 8 (2014): e7-e9, accessed July 30, 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4103249/; and “Training Law Enforcement to Identify Overdose and Use Naloxone,” Harm Reduction Coalition, accessed July 30, 2018, http://harmreduction.org/overdose-prevention/training-law-enforcement-to-identify-overdose-and-use-naloxone/.

12 Virginia Beach, Virginia, Police Department.

13 Alan Suderman, “Virginia Now Allows Anyone to Buy Naloxone, an Opioid Overdose Antidote,” WJLA, November 21, 2016, accessed July 30, 2018, http://wjla.com/news/local/virginia-now-allows-anyone-to-buy-naloxone-opioid-overdose-antidote; and Nina Feldman, “Philly Launches Campaign Urging Citizens to Carry Lifesaving Naloxone,” WHYY, March 13, 2018, accessed July 30, 2018, https://whyy.org/articles/philly-launches-campaign-urging-citizens-carry-life-saving-naloxone/.