School Resource Officers and Violence Prevention: Best Practices (Part One)

By Katherine W. Schweit, J.D., and Ashley M. Mancik, M.A.

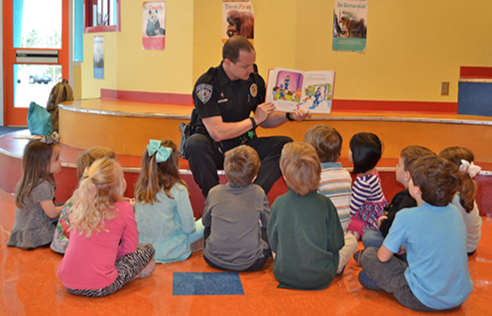

Photo courtesy of the National Association of School Resources Officers (NASRO).

“This is our first task as a society, keeping our children safe.”

—former president Barack H. Obama II1

As part of former president Obama’s 2013 initiative to stop gun violence and focus on keeping children safe, he prioritized making schools more secure and implemented an executive order allowing for additional resources and incentives for education officials to hire more school resource officers (SROs).2 Law enforcement agencies play a vital role in school safety.

However, SROs need adequate training and support from the school, district, and police department. Navigating how to effectively work within this environment—with its own set of challenges and considerations—takes planning and patience.

As part of its continued commitment to support law enforcement, the FBI interviewed a group of experienced SROs and law enforcement officers (LEOs) with a combined 150 years of experience. They shared their advice on pitfalls to avoid and successful strategies to implement. These united voices are matched with the latest research.

This two-part article offers help to SROs and other LEOs working in kindergarten through 12th grade educational settings. Part one addresses considerations in establishing such a partnership, including potential challenges. Part two will focus on targeted violence prevention strategies. Further, the FBI offers a free guide, Violence Prevention in Schools: Enhancement Through Law Enforcement Partnerships, that highlights key points from both parts of the article.3

BUILDING A PARTNERSHIP

The first step in establishing a law enforcement-school partnership involves determining the needs of the school. Not all schools will require or want full-time LEOs or an SRO program.4 An initial needs assessment or climate survey can help determine the level and scope of police involvement desired by the district, administration, faculty, and parents.

At a minimum, the school should have a relationship with area law enforcement and a point of contact in the local police department. Behind areas of commerce, educational facilities represent the second-most common locations for a devastating type of targeted violence—active shooter incidents.5

Ms. Schweit is chief of the Violence Prevention Section in the FBI’s Office of Partner Engagement in Washington, D.C.

Ms. Mancik is an FBI honors intern and a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at the University of Delaware in Newark.

If possible, a school administrator or superintendent should participate in the selection of an officer to place in the school. Research has found that involvement of school personnel during this process increases the effectiveness and acceptance of the officer.6

- In coordination with the school, conduct a needs assessment to determine goals and the level and scope of law enforcement involvement.

- At a minimum, ensure the school has a relationship with area law enforcement and a point of contact in the local police department.

- Include a school administrator or superintendent in the SRO selection process.

Specifying the Relationship

All roles, responsibilities, and duties of both law enforcement and school officials must be settled in advance of establishing the partnership. These decisions must be recorded in a memorandum of understanding (MOU), memorandum of agreement (MOA), or other policy document used as part of the district and school administration process. Police departments also may choose to include some of these considerations in an operational protocol. These decisions need to fit the specific partnership and will vary based on needs and resource availability.

Answering a number of questions can help start conversations that lay the foundation for a permanent relationship.

- Who represents each entity?

- How much involvement and commitment is required, during and after school hours, considering both resources and time?

- What are the overall aims and objectives?

- Which roles do the various parties (e.g., SROs, teachers, and school administrators) play on a daily basis?

- Do these roles change in a crisis situation?

- To whom does the LEO report—police supervisor or school administrator?

- How will the SRO’s interactions be documented?

- When and how will conflicts between agencies be resolved?

- Will the armed officer be in uniform or plain clothes?

- What are the procedures for working with an outside organization (e.g., child service agency)?7

More complex issues involving legal matters should be discussed with input from the school or district’s general counsel or the department’s legal counsel. Some key repeating concerns to resolve early include procedures, such as documentation and notification of search and seizure matters, interviews of juveniles, police access to students, information sharing, and privacy restrictions.

Considering Initial Training Needs

In addition to regular law enforcement instruction, LEOs assigned to schools should receive specialized training prior to their assignments. They should become aware of the current laws applicable in an educational environment. Critical knowledge includes state and federal laws regarding privacy and juveniles, search and seizure, and information sharing.8 Initial, as well as ongoing, training should cover many different areas.

- Information sharing and laws regarding juveniles

- Cultural sensitivity and linguistic differences

- Problem solving

- Critical incidents and crisis management

- School safety

- Threat assessment

- Reporting and dispatch systems

- Adolescent development

- Diversion programs

- Mental health

- Bullying prevention

- Drug awareness and substance abuse

- School discipline and code of conduct

- Psychological First Aid (PFA)

- Work with students who have disabilities9

Photo courtesy of the National Association of School Resources Officers (NASRO).

Although this list may seem daunting, federal and state government agencies, as well as local and national law enforcement organizations, offer tremendous resources, mostly online. LEOs assigned to SRO positions also can meet with area mental health officials, district counselors, prosecutors, and other persons trained in many of these areas and assigned to such matters. The relationships developed will strengthen the SRO’s knowledge and build a list of available resources for threat assessment and threat management matters.

ENHANCING AND MAINTAINING RELATIONSHIPS

Assessing Continuously

To evaluate the partnership and ensure its effectiveness, SROs should schedule times to formally assess the relationship and progress toward goals. For example, conducting an annual school climate survey will aid in assessing the strengths, identifying areas for improvement, and monitoring progress.10 Many districts and schools conduct these surveys as a matter of course, making it easier to become part of that process. Additionally, tracking threats and other school crime statistics can help assess changes in these behaviors over time. Such efforts must comply with applicable record-retention laws.

Communicating Often

Addressing emerging problems with partners proves critical. To ensure constant communication, brief, scheduled meetings (e.g., monthly or quarterly) between all parties can help in assessing goals, addressing potential problems or challenges, and identifying additional needs.

Infrequent or poor communication may contribute to students “slipping through the cracks” or not having their needs met. If officers do not work in the school regularly, various immediate communication channels must be in place prior to an emergency situation.

Critical discussions with district and school officials involve potential building entry considerations. This includes multiple accesses to necessary key codes and the general layout of the school buildings and grounds.

Others in the department should know communication and access options. Details about who can access digital codes; keys to gates and doors; and any security-related equipment, such as cameras, should be written out. Failure to have an effective communication plan can create grave risks when, for example, only one person has authorization to grant permissions, give accesses, or initiate critical incident responses. All planning should focus on avoiding singular points of failure.

Collaborating with Community Agencies

Collaborating with community organizations (e.g., social service agencies; juvenile justice departments; and local groups, such as churches and youth leagues) helps present a broader picture of troubling or suspicious behavior than work with schools alone.11 This “integrated systems approach” also proves useful for ensuring students receive the resources and services they may need.12 At a minimum, officers should become familiar with community organizations, and everyone should have a ready list of contacts and information about what help they can provide.

When working with other community agencies, SROs must learn how to use information-sharing laws (e.g., Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act [FERPA] regulations) and develop a protocol with the other organizations.13 Also, they should collaborate with all area police departments to integrate school security with broader neighborhood safety efforts.

Finally, all parties (e.g., campus officials, school-based LEOs, local law enforcement agencies, fire departments, and EMS personnel) must participate in crisis intervention training. This step is critical.

When planning and hosting exercises, it is critical to include the entire community—those who will respond when an emergency occurs—to ensure clear role delineation and consideration of all pertinent aspects, including the effect on adjacent properties and postincident responses.

Involving Parents

Open communication with parents also can aid in interactions with students and the identification of concerning behaviors. Both family members and the broader community play a large role in promoting a healthy environment and assessing risk. SROs should meet with parents early and often, not only when a student is in trouble or an incident has occurred. It is important to share both positive and concerning information.

MEETING POTENTIAL CHALLENGES

Because law enforcement agencies focus primarily on campus safety and schools mainly on education, conflicts and unique challenges can arise.14 SROs working in schools may encounter resistance from campus personnel, parents, or the larger community. Conflicts should not be viewed negatively. Instead, a variety of opinions and proprieties can help ensure the consideration of all aspects of a situation before action is taken.

“The first step in establishing a law enforcement-school partnership involves determining the needs of the school.”

Clearly defining the roles of the SRO in the MOU helps minimize resistance and conflict. Explicit guidelines must dictate who has authority in various situations. These should cover substance-related incidents (e.g., disciplinary and criminal matters) and location-based concerns both inside and outside of the school. For example, these include those occurring in the classroom, administrative offices, lunchroom, or gymnasium.

Often, the issue arises regarding when to involve an SRO in school disciplinary matters. The MOU must clearly distinguish between the handling of disciplinary actions and violations of the law. School administrators and teachers, guided by district and school rules and procedures, hold responsibility for disciplinary actions, while the SRO addresses legal violations and threats to the security of the school, students, and employees.

In coordination with the school, SROs must specify the handling of potential gray areas—actions not strictly criminal or purely disciplinary in nature. They should discuss with the administrative team potential examples where these might occur.

Concerning students, SROs should avoid arrests or criminal charges when more metered responses exist. Use of aggressive tactics for minor infractions can strain relationships, negatively impact school climate, discourage students from reporting potentially harmful or suspicious behavior, and disproportionately introduce youth into the criminal justice system.15

When speaking with school officials, parents, or concerned individuals, SROs must emphasize law enforcement’s main goal of keeping students and schools safe, which constitutes a necessary component for successful learning.16 Building on this consensus with the school’s focus on education helps mitigate potential resistance to SROs and other LEOs in schools.17

As another way to minimize such problems, SROs should discuss with district and school officials the benefits of a more holistic or comprehensive approach to school safety. For example, they can discuss how the sanctioning of criminal violations for substance abuse can be supplemented with resources to help address the underlying issues that may contribute to the problem.18

This comprehensive approach should accompany specialized training in the areas identified earlier in the article. Working closely with community agencies makes this easier and more effective.

- Emphasize the main goal of keeping students safe, which proves necessary for successful learning.

- Ensure the MOU specifies guidelines, roles, ways to resolve conflicts, and who has authority in various situations.

- Make clear distinctions between the handling of disciplinary versus criminal actions, and include gray areas.

- Avoid harsh disciplinary policies when possible; these can strain relationships, negatively impact school climate and academic achievement, and discourage reporting.

- Take a comprehensive approach to school safety; provide resources to address underlying issues and problems, whether criminal (e.g., substance abuse) or not (e.g., mental health).

“All roles, responsibilities, and duties of both law enforcement and school officials must be settled in advance of establishing the partnership.”

Finally, during all interactions, approaches, and communications with students, SROs must remember the child’s developmental maturity, possible prior trauma, cultural or linguistic differences, and previous experiences with law enforcement.19 They also should consider how perceptions and reactions may change throughout an interaction.

CONCLUSION

School resource officers, as well as school and law enforcement officials who support them, hold responsibility for the safety of their charges. In particular, this role suits SROs well. To establish a successful SRO program, the school, district, and police department must give particular attention to legal differences between operating in a school environment and in the community; developmental considerations related to working with juveniles; and the need for collaboration and open communication with school personnel, parents, first responders, and other community agencies on an ongoing basis.

When a carefully planned SRO program results from the combined efforts of the law enforcement agency and the district involved, confusion and conflict can be avoided. This allows SROs to become integral players in bridging the gap between a healthy educational environment and disruptive and escalating situations that may only have a law enforcement solution.

Ms. Schweit can be contacted at Katherine.schweit@ic.fbi.gov and Ms. Mancik at Ashley.mancik@ic.fbi.gov.

Endnotes

1 Barack H. Obama II and Joseph R. Biden, Jr., “Remarks by the President and the Vice President on Gun Violence” (January 16, 2013), accessed November 17, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/01/16/remarks-president-and-vice-president-gun-violence.

2 The White House, Now Is the Time: The President’s Plan to Protect Our Children and Our Communities by Reducing Gun Violence (January 16, 2013), accessed February 22, 2017, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/wh_now_is_the_time_full.pdf.

3 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Violence Prevention in Schools: Enhancement Through Law Enforcement Partnerships (March 2017), accessed March 27, 2017, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/violence-prevention-in-schools-march-2017.pdf/view.

4 Now Is the Time: The President’s Plan to Protect Our Children and Our Communities By Reducing Gun Violence (January 16, 2013), accessed November 17, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/wh_now_is_the_time_full.pdf; and U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Center for Problem Oriented Policing, Assigning Police Officers to Schools, Barbara Raymond, Problem Oriented Guides for Police, Response Guides Series, No. 10 (April 2010), accessed November 17, 2016, http://www.popcenter.org/Responses/pdfs/school_police.pdf.

5 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Texas State University, A Study of Active Shooter Incidents in the United States Between 2000 and 2013, J. Pete Blair and Katherine W. Schweit (September 16, 2013), accessed November 17, 2016, https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/office-of-partner-engagement/active-shooter-incidents/a-study-of-active-shooter-incidents-in-the-u.s.-2000-2013; and U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Active Shooter Incidents in the United States in 2014 and 2015, Katherine W. Schweit (2016), accessed November 17, 2016, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/activeshooterincidentsus_2014-2015.pdf.

6 John Rosiak, “Developing Safe Schools Partnerships with Law Enforcement,” Forum on Public Policy, no. 1 (2009), accessed November 17, 2016, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ864815.pdf.

7 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Memorandum of Understanding Fact Sheet (May 2015), accessed November 17, 2016, https://cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/2015awarddocs/chp/chp_mou_fact_sheet.pdf; Maurice Canady, Bernard James, and Janet Nease, To Protect & Educate: The School Resource Officer and the Prevention of Violence in Schools (Hoover, AL: National Association of School Resource Officers, 2012), accessed November 17, 2016, https://nasro.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/NASRO-To-Protect-and-Educate-nosecurity.pdf; Raymond; and Rosiak.

8 Rosiak.

9 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, COPS Hiring Program School Resource Officer Scholarship Opportunity for NASRO Training: Improving School Safety Through Targeted SRO Training, fact sheet (September 2014), accessed November 17, 2016, https://cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/2014_CHP-SRO-FactSheet3_092613.pdf.

10 U.S. Secret Service and U.S. Department of Education, Threat Assessment in Schools: A Guide to Managing Threatening Situations and to Creating Safe School Climates, Robert A. Fein, Bryan Vossekuil, William S. Pollack, Randy Borum, William Modzeleski, and Marisa Reddy (July 2004), accessed November 18, 2016, https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/threatassessmentguide.pdf.

11 U.S. Secret Service and U.S. Department of Education, The Final Report and Findings of the Safe School Initiative: Implications for the Prevention of School Attacks in the United States, Bryan Vossekuil, Robert A. Fein, Marisa Reddy, Randy Borum, and William Modzeleski (July 2004), accessed November 18, 2016, https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/preventingattacksreport.pdf.

12 Ibid., 32; Raymond; and Rosiak.

13 U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Secret Service, Making Schools Safer (May 2013), accessed November 18, 2016, http://cdpsdocs.state.co.us/safeschools/Resources/Secret%20Service/SSI_makingschoolssafermay2013.pdf.

14 Raymond; and Rosiak.

15 Brad J. Bushman, Sandra L. Calvert, Mark Dredze, Nina G. Jablonski, Calvin Morrill, Daniel Romer, Katherine Newman, Geraldine Downey, Michael Gottfredson, Ann S. Masten, Daniel B, Neill, and Daniel W. Webster, “Youth Violence: What We Know and What We Need to Know,” American Psychologist 71, no. 1 (2016): 17-39, accessed November 18, 2016, http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-a0039687.pdf; and Katherine S. Newman, Cybelle Fox, Wendy Roth, Jal Mehta, and David Harding, Rampage: The Social Roots of School Shootings (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2004).

16 Rosiak.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.; and Tips for School Administrators for Reinforcing School Safety (Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists, 2015), accessed November 18, 2016, http://www.houstonisd.org/cms/lib2/TX01001591/Centricity/Domain/8052/ School%20Safety%20Tips%20for%20Administrators.pdf.