Taking A.I.M. at Officer Safety

By Kevin Harris

Every year, over 50,000 police officers are assaulted, and an average of 50 are feloniously killed in the line of duty. In 2021, 73 officers were feloniously killed, marking one of the deadliest years in recent law enforcement history.1 The statistics are important, but understanding why officers are being killed and assaulted is critical for lowering the numbers.

Over a 20-year period, the FBI’s Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program conducted three groundbreaking studies that examined felonious assaults on police officers: Killed in the Line of Duty (1993), In the Line of Fire (1997), and Violent Encounters (2006).2 Researchers tried to develop a profile of someone likely to kill or violently assault a police officer. In the end, and at the risk of sounding overly simplistic, they discovered it could be almost anyone.

Protecting Officers

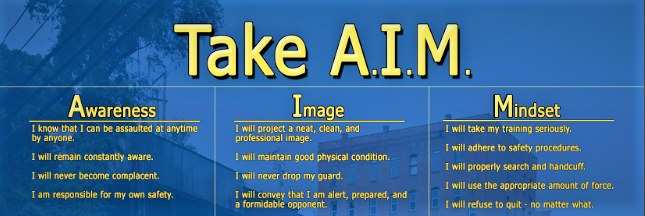

Without an offender profile, how can officers protect themselves? Investigators in Violent Encounters developed a technique officers could implement before starting their shift to assist them during potentially deadly encounters. It consists of three components, recalled using the mnemonic “Take A.I.M.”

Mr. Harris, an FBI police veteran, is an instructor with the bureau’s Officer Safety Awareness Training Program in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

Awareness

Everyone — including law enforcement officers — tends to think that bad things only happen to other people.3 However, officers must remain aware that they can be assaulted while performing their duties at any time by anyone.

Since they cannot anticipate potential assaulters and circumstances of being assaulted, officers need to remain aware of their total environment. They must understand that every situation has unknown circumstances and avoid complacency, regardless of their years of experience.4

Many veteran officers view these assaults as a problem for inexperienced officers. However, when looking at those feloniously killed in the line of duty from 2011 to 2020, 71% had six or more years of service.5 These statistics show that this affects all officers, and they are ultimately responsible for their own safety.

Image

Officers must understand that the image they think they project may not be perceived the same way by an offender, so it is important to be as professional as possible.6 Many offenders in the research studies noted that the officers they assaulted seemed unprepared or appeared to just be “going through the motions.”7

In the Line of Fire noted that 64% of offenders who assaulted officers stated that their attacks were “impulsive, unplanned, or opportunistic.”8 In other words, nearly two-thirds of the offenders studied were looking for a window of opportunity or waiting for an officer to make a mistake. Absent these opportunities, the offenders may not have attacked. Officers must realize they can be courteous to citizens while maintaining their professional demeanor.9

Mindset

All training should be taken seriously. The research studies showed that failing to follow safety protocols or taking shortcuts was a factor in many officer assaults.10 Proper handcuffing, searching, and other tactics must always be performed, regardless of the officer’s perception of the situation. If officers are assaulted, they must have the mindset that they will continue to fight and survive no matter the circumstances.

“Officers must realize they can be courteous to citizens while maintaining their professional demeanor.”

Conclusion

Assaults of on-duty officers are an unfortunate but inevitable part of law enforcement. Prevention of all incidents will likely never occur. However, officers can take measures to mitigate their chances of being assaulted while also increasing their likelihood of surviving if it does happen. Take A.I.M., developed from LEOKA research, is a simple technique that officers can use daily to potentially save their lives.

The Take A.I.M. brochure, as well as studies cited in this article, can be found in the Officer Safety Awareness Training (OSAT) community on the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal (LEEP). For more information about LEEP or to receive officer safety awareness training, please contact the OSAT Program at OSAT@fbi.gov.

Mr. Harris can be reached at kjharris@fbi.gov.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Crime Data Explorer,” accessed June 7, 2022, https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/downloads#leokaDownloads.

2 U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Killed in the Line of Duty: A Study of Selected Felonious Killings of Law Enforcement Officers (Clarksburg, WV, 1992), https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/killed-line-duty-study-selected-felonious-killings-law-enforcement; U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, In the Line of Fire: Violence Against Law Enforcement; A Study of Selected Felonious Assaults on Law Enforcement Officers, Anthony Pinizzotto, Edward Davis, and Charles Miller III (Clarksburg, WV, 1997), https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/line-fire-study-selected-felonious-assaults-law-enforcement; and U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Violent Encounters: A Study of Felonious Assaults on Our Nation’s Law Enforcement Officers, Anthony Pinizzotto, Edward Davis, and Charles Miller III (Clarksburg, WV, 2006), https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/violent-encounters-study-felonious-assaults-our-nations-law.

3 Violent Encounters, 142.

4 Ibid.

5 “Crime Data Explorer.”

6 Violent Encounters, 142.

7 In the Line of Fire, 30.

8 Ibid.

9 Violent Encounters, 142.

10 In the Line of Fire, 44.