Focus on Training

Corrective Feedback in Police Work

By Peter J. McDermott and Diana Hulse, Ed.D.

A central mission of police organizations is the ongoing development of personnel. Police recruits are trained and supervised in the work performance areas of tactical skills, communication abilities, understanding of human interactions, and the development of proper documentation skills. They need positive feedback that reinforces successful performance and corrective feedback that communicates that their performance does not meet identified criteria. Supervisors need to have the skills for providing corrective feedback to their personnel.

Because exchanging corrective feedback is complex and multifaceted, proficiency in delivering it requires an understanding of what feedback is, how it can be used to full advantage, and why it is important to prepare the giver and receiver.1 Corrective feedback occurs when a field training officer (FTO) identifies that recruits’ performance does not meet expectations and prepares to speak with them about changing their behavior.

Background

The importance of corrective feedback is illustrated perfectly through clinical training in graduate counselor education programs. In counseling programs, students participate in scholastic and clinical settings, and their work with clients receives intensive, semester-long supervision. The monitoring instructors and supervisors evaluate students’ intervention, conceptualization, and professional skills and judge their ability to link theory and content knowledge to effective clinical practice with real clients.

As students receive clearly articulated expectations for feedback exchange and talk through their feelings about receiving corrective responses, they develop a greater attraction to the ongoing feedback process. Since 1994, the Corrective Feedback Instrument-Revised (CFI-R) has served as a tool to encourage conversation between supervisors and personnel about the complex topic of feedback and its role in clinical supervision.2 Counseling students must complete the CFI-R, and their responses provide opportunities for conversation in individual sessions with their supervisors and in group settings with other students. Conversations at the beginning of the semester help students frame the feedback process as a means for growth and development, rather than one of anxiety and defensiveness.

Just as clinical supervisors benefit from examining counseling student responses on the CFI-R, FTOs can benefit from reviewing and discussing recruit responses. In field training programs, recruits are expected to translate classroom instruction to acceptable performance in motor vehicle stops, criminal investigations, domestic violence, and other conflicts. They receive mandatory feedback on a daily basis for 10 to 14 weeks. As a result, FTOs can gain valuable information about the range of reactions that recruits may have to receiving corrective feedback. Additionally, when FTOs examine their own responses to corrective feedback, they increase their understanding of how their feelings and reactions may enhance or hinder their work as supervisors.

At this point, some might say “What’s the big deal here? We understand the need for feedback, and it’s being done.” One of the authors argues otherwise. “It’s not easy, or it would be done on a regular basis, and I know that it is not. I have been inquiring in first-line leadership classes dating back to 1985 about the amount of feedback that students receive over their careers; it is pathetically low.”3

Police organizations are built on feedback. But, giving and receiving corrective feedback often intimidates people because it involves personal risk taking.4 Some supervisors may not know how to give corrective feedback and may have their own anxieties that impede delivering it in a way usefully received and processed by personnel.5 As a result, behavioral change is not initiated, and professional development is stunted for both the giver and receiver. Predictably, the group or organization suffers in its mission to provide service because no impetus for growth and change exists. However, the CFI-R, paired with the Cycle of Effective Feedback (CEF), can assist supervisors in preparing for and delivering corrective feedback that will be heard, understood, reflected upon, and translated into positive behavioral change within their police organizations.

Corrective Feedback Instrument-Revised

One of the functions of the CFI-R is to serve as a stimulus for conversation about potential obstructions to hearing, processing, and translating feedback into desired behavioral change. The CFI-R consists of 30 items presented in a 6-point Likert format: strongly disagree, disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, agree, and strongly agree. All items focus on 1 of 6 factors: feelings, evaluative, written, leader, clarifying, and childhood memories.

FTOs can require recruits to complete the 30 items in advance of the field training program. Responses likely will vary following on a number of concerns. One recruit might agree with the item “When I receive corrective feedback, I think I have failed in some way,” while another might agree with “I usually am too uncomfortable to ask someone to clarify corrective feedback delivered to me.”6 Use of the CFI-R can help illuminate challenges for the FTO to address, which can be acted upon using the CEF.

Cycle of Effective Feedback

“…giving and receiving corrective feedback often intimidates people because it involves personal risk taking.”

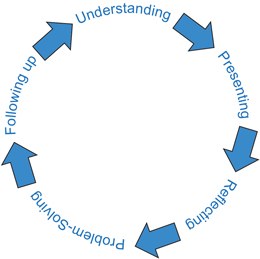

The 5 elements in the CEF provide the FTO with a sequence of steps to follow. These steps include:

- understanding recruits and their idiosyncratic responses to feedback;

- presenting the corrective feedback to recruits based on this understanding;

- reflecting on the feedback exchanged with the recruits;

- enacting problem solving steps to acquire the desired behavior; and

- engaging in follow-up assessments to evaluate desired outcomes.

Depending on the results of these follow-up steps, the FTO may need to repeat the cycle again by focusing on one, some, or all of the 5 elements until recruits demonstrate expected performance criteria.

Understanding Recruits

As FTOs gain an understanding of feelings and reactions to corrective feedback, they can begin to design more effective ways to interact with each recruit. The FTO can explore recruit responses to questions, such as “When someone gives you corrective feedback, what do you think, what do you feel, and what do you do?” as well as ask recruits how they would give out feedback. Through this exploratory process using the CFI-R, the FTO and recruit begin to develop a relationship that reduces the negativity associated with corrective feedback.

These steps are particularly easy to accomplish at the beginning of a field training program because they prepare the recruit for accepting continual feedback and give them a better understanding of its goals, which will enhance learning. For example, the FTO might say, “I noticed that on your responses to the CFI-R you indicated that you equate corrective feedback to criticism. Because you will be receiving corrective feedback from me throughout the program, I want to discuss how I can make the feedback I give you useful and productive.”

This statement demonstrates that the FTO has taken time to consider the recruit’s responses on the CFI-R and is committed to building an up-front relationship that benefits the delivery of effective feedback. The FTO also can prepare the recruit for the language of feedback, which includes using “I” statements, speaking in behavioral terms, and applying phrases, such as “What did not work in your performance today was….” This accentuates performance criteria over personal judgment of the recruit.

Presenting Feedback

During a motor vehicle stop conducted by a recruit and observed by the FTO, it is determined that the recruit conveyed a rude and disrespectful tone toward the vehicle operator. The function of the FTO then is to give corrective feedback in a manner that will eliminate future negative interactions and at the same time put the recruit in a learning mode as opposed to a defensive one. The FTO has learned that the recruit interprets corrective feedback as criticism. The FTO might say, “You gave me the impression of rudeness, and you did not appear to demonstrate respect. Can you share with me your impression of the interaction?”

Reflecting on Feedback

Reflection is a critical point in the cycle where recruits clarify their understanding of the feedback. Three items on the CFI-R specifically address clarification. One item reads “When I am not sure about the corrective feedback message delivered to me, I do not ask for clarification.”7 A recruit’s agreement with this item indicates some hesitation that requires exploration. Perhaps, recruits feel overwhelmed, or their style is to act as if they understand the feedback because to do otherwise might convey incompetence. Whatever the reasons, the FTO should ensure that recruits understand the message. One way to do so is to have recruits repeat back a message given to them.

Problem Solving and Following Up

Once feedback has been reflected upon by recruits, they have another opportunity to improve their conduct. The FTO will review any questions or concerns they may have and possibly suggest some ways for recruits to approach their next motor vehicle stop. As a follow-up, the FTO will observe the next interaction between the recruit and a motor vehicle driver and will evaluate the presence of positive change, some change, or no change. The FTO may revisit elements of the cycle as a result of this assessment. Thus, the cycle continues.

Conclusion

Effective environments for giving and receiving feedback will enhance the professional development of personnel while achieving the mission of a police organization. Interpersonal skills competencies combined with an understanding of how to prepare and present corrective feedback are fundamentals for success. Field training officer programs provide an excellent place to set in motion effective feedback skills for the giver and receiver. These programs are intense, and recruits can choose to endure what they perceive as a noxious experience, or they can become engaged in the learning process.

A clinical supervisor once said to counseling students in a beginning practicum class, “You never will have this many people interested in you at any one time ever again.” This statement could promote fear and dread, or it could convey a message of support—an invitation to engage to the fullest degree in the learning process with professionals dedicated to helping their personnel be the best they can be. When these recruits understand the purpose of feedback and have a chance to voice their concerns in a supportive climate with those who provide such input, the chances increase that they will be more open to corrective feedback and its link to their personal and professional growth and development.8

“Interpersonal skills competencies combined with an understanding of how to prepare and present corrective feedback are fundamentals for success.”

Peter J. McDermott welcomes readers’ questions and comments at pete06422@yahoo.com.

Mr. McDermott is a retired captain from the West Hartford and Windsor, Connecticut, Police Departments and a retired instructor from the Connecticut Police Academy.

Dr. Hulse is a professor and chair of the Counselor Education Department at Fairfield University in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Endnotes

1 Diana Hulse-Killacky, Jonathan J. Orr, and Louis V. Paradise, “The Corrective Feedback Instrument-Revised,” Journal for Specialists in Group Work 31 (2006): 264.

2 Hulse-Killacky, Orr, and Paradise, 263; Diana Hulse-Killacky and Betsy J. Page, “Development of the Corrective Feedback Instrument: A Tool for Use In Counselor Training Groups,” Journal for Specialists in Group Work 19 (1994): 197.

3 Peter J. McDermott, a 47-year veteran of law enforcement, including 20 years of teaching supervision classes.

4 Hulse-Killacky and Page, 198.

5 Hulse-Killacky and Page, 208.

6 Hulse-Killacky, Orr, and Paradise, 271, 268.

7 Hulse-Killacky, Orr, and Paradise, 268.

8 Hulse-Killacky, Orr, and Paradise, 277.