Perspective

Evaluating the Paramilitary Structure and Morale

By David Cruickshank, M.S.

Law enforcement agencies constantly struggle with public perception as a result of ever-evolving demands placed upon their profession and by shifting leadership practices that attempt to meet those demands. As policing moves to meet the needs of the 21st century, law enforcement leadership has begun to incorporate business leadership practices and models, but the looming question is whether or not the culture of policing stands ready to accept the paradigm shift. Ultimately, how would these business and paramilitary practices coalesce?

BUILDING A BETTER MODEL

Although more modern motivational theories exist, many theorists still use the one proposed by A.H. Maslow in 1943.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs outlines that to move toward self-actualization, safety and security are necessary; however, in current societal trends, higher- and lower-order Maslow needs are not seen as separate, creating confusion as to who holds responsibility for fulfilling these needs.2 Currently, law enforcement has responsibility for not only the balance between the public’s need for safety and service but also for the definition and fulfillment of both. Without a balance between the two, citizens are either dissatisfied with law enforcement or concerned with their safety—both negatively affect law enforcement morale and job satisfaction.

Many complex issues compound this problem. In particular, two related issues are becoming exceedingly difficult to distinguish—public safety and public service. As society moves forward, the demand for a greater availability and range of services has increased. The list of services people believe they are entitled to and that law enforcement must provide grows steadily. Because some citizens could interpret any given service as pertaining to public safety and others for public service, this topic becomes further blurred.

For instance while traffic control mainly serves the public’s need for safety, numerous traffic-control services could be categorized as service oriented. For example, pertaining to a residential parking complaint, law enforcement typically would investigate and provide enforcement without an imminent or, even, likely threat to public safety.

Some options available to law enforcement to deal with these issues are more viable than others. Examples include privatizing certain services, establishing a parking authority, or hiring a traffic officer, which prove more desirable than the reversal of decades-old responsibility consolidation. The answer to balancing this scale also may lie in shifting leadership practices and relying on the paramilitary structure to accommodate the changes in society by “adapt and overcome.” Agencies forever will be driven by the public perception of what their role should be in society, rather than what is in citizens’ best interests. Numerous institutions, such as the media, elected police commissions, and local government organizations, always will ensure that law enforcement remains driven by public perception. Agencies must adapt to meet these challenges and provide the services that the public demands while balancing citizens’ often-under-recognized need for safety.

BREAKING POINT

Officer Cruickshank serves with the Berlin, Connecticut, Police Department.

While many self-proclaimed law enforcement watchdog groups exist, Injustice Everywhere has reported an alarming societal cost figure. Based solely on media reports and misconduct-related civil judgments and settlements, excluding sealed settlements, court costs, and attorney fees, law enforcement agencies incurred approximately $346,512,800 in costs in 2010 in lawsuits in the United States alone.3 When coupled with high rates of turnover, sick-leave abuse, substance abuse, and suicide within the profession, a problem of overwhelming proportion becomes evident. Agency morale problems have comprised a common factor in all of the issues facing law enforcement. The paramilitary structure of policing itself has bred some of these issues. One expert suggested that fixed and rigid communication channels breed inefficiency and frustration when personnel try to accomplish the agency’s mission.4 Further, the recognized principles of community policing “come into direct conflict with the paramilitary and bureaucratic structure of police organizations.”5 If the paramilitary law enforcement structure and resulting practices create controversy or morale issues, why stay with it?

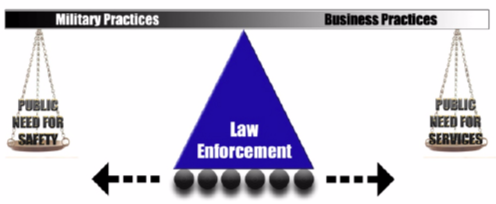

The problem remains that without a better-working model for policing, the paramilitary model remains what law enforcement has to work with, and it probably will not change in the near future. It serves as a middle ground between the military model—driven by the mission and compliance—and the business model—fueled by profit and customer satisfaction. Although valid arguments support the military and business models, the paramilitary model for policing becomes necessary if selecting between the three options. The military model fails to address public-service orientation, and the business model does not address life-critical mission orientation. Morale can serve as an indicator when identifying roadblocks to a smoothly functioning agency. So, how does this paramilitary model specifically affect law enforcement morale in the 21st century, and what leadership practices are responsible?

Numerous theories exist pertaining to law enforcement morale. All have individual merit, but fail to address the big picture. One popular theory argues that leaders do not properly lead. Regardless of industry, it always is easy to blame management and leadership practices for low morale, an especially easy out for agencies as the profession evolves so rapidly and leadership styles often change too slowly. Coupled with the fact that law enforcement is the public face for the entire criminal justice system, any changes to the laws or inefficiencies in the justice system result in a negative image for police, thereby lowering job satisfaction. Leadership practices can both raise and lower morale, but they are not the sole contributing factor.

Another popular theory on morale, largely held by leadership staff familiar with current trends, is that, at its root, morale is a personal issue. While leadership practices may affect morale, it, ultimately, involves every individual’s personal traits and characteristics. After all, as officers are aware, chiefs do not attend every roll call to announce that “today will be a bad day for all of you.” Ultimately, individuals’ attitudes sculpt how their day will be and whether or not they positively will interact with their teammates. Those who believe they have a good job typically are positive, and those who believe otherwise usually are negative. This theory also defers ownership of morale issues too easily.

No single reason exists for lowered workplace morale, and that big picture rarely is seen. When individuals experience low job satisfaction, they often point out one or two changes that they believe could turn everything around. However, even correcting these specific items typically does not improve morale significantly because new issues constantly arise. The solution is to improve morale by addressing the factors affecting it. Agencies should develop a better model that incorporates flexible leadership practices applicable to the mission of the day and properly prepare individuals for what will be expected of them. This solution incorporates both primary philosophical reasons for lowered morale while improving both agency function and employee job satisfaction. Thus, stress points within the organization structure are tempered.

MOVING FORWARD

Law enforcement agencies adopted the paramilitary model because policing originally was designed primarily to address the public’s need for safety. This more closely was related to military practices, and by adopting this model, command and control was maintained with few major issues. The paramilitary model for policing has served the mission of law enforcement well over the years by allowing militaristic command-and-control during emergencies and, yet, with the model’s evolvement, a more service-oriented, customer-friendly side during day-to-day operations.

The mission of law enforcement has not changed over the years, but it certainly has expanded. Policing must remain flexible enough to maintain the balance between safety and service, yet proactive enough in its leadership strategies to sustain itself and move away from the breaking point. How is this done?

Using morale as an indicator and improving some leadership practices holds the answer. It is important to recognize that the militaristic style of leadership and the resulting practices are efficient and effective in meeting the public need for safety, while the business style of leadership and the resulting practices are equally efficient and effective at meeting the public need for service. As agencies move more toward service-oriented policing by expanding community programs and implementing community-service-based policing, it would be prudent to build upon the successful leadership styles and practices of the business profession that always have targeted the need for service. The military long has understood the value of high unit morale, but with money at stake, the business world has become exceedingly efficient at understanding and working to improve morale, increase job satisfaction, and better meet the need for service. With the ultimate goal of increasing customer satisfaction and profit, businesses invest heavily in everything from leadership-skills camps to “dress-down Fridays,” but can law enforcement adapt these techniques to work in an environment with restrictive budgets and life-or-death situations? Some common reasons for lowered morale in law enforcement exist that have been associated with the paramilitary structure. Coupled with some basic business-based solutions, the paramilitary model can be made more efficient and able to meet the new demands placed upon it.

| Law Enforcement Morale Issue | Business Practice-Based Morale Improvement |

| Increased workloads | Restructuring, task prioritizing, and consolidating tasks to reduce or better manage the individual workload |

| Internal agency inefficiency | Reducing internal communication roadblocks and increasing communication ability |

| Lack of clear direction | Verifying that not only are the supervisors well fit for their positions but regularly ensuring that they are all in agreement |

| "Not my job" syndrome | Providing a better understanding about the job personnel have been hired to do and why it is necessary and important to the organization |

| Lack of job satisfaction | Meeting individually with employees to determine where they see themselves and how personal and agency goals can be aligned to meet both of these expectations |

STRENGTHENING LAW ENFORCEMENT NOW

Great businesses are built on profitability and customer satisfaction. They accomplish their missions by trimming company “fat” and workplace inefficiencies to maximize the work effort of personnel while reducing employee stress. These business models also can be applied to policing. They serve as easy starting points toward balancing the scale as leadership models and practices do not need to be drastically changed from the paramilitary model to the business model. Agencies just need to remove a few organizational roadblocks using simple business techniques. Currently, law enforcement typically only works on trimming the fat when faced with a budget crisis, and, even then, it usually involves layoffs, rather than restructuring, increased efficiency, and overall improvement. Agencies have many ways in which to immediately adopt these fat-trimming business practices for their betterment. In most cases, these changes can be made without exposing the agency to added liability, a problem more unique to law enforcement agencies than other organizations.

Forms

Every police agency has a seemingly unlimited amount of forms. Singling out one or two that officers must fill out on a daily basis and doing away with them could save time and energy. Multiple forms also could be combined into one to simplify paperwork.

Policies and Procedures

While every chief implements new policies and procedures, many usually are retained from previous leaders and are now antiquated. Perhaps, a policy or practice for an event that happened once in 25 years can be abolished without affecting the agency’s liability risk.

Community Services

Are some services offered or provided to the community that the staff strongly dislike or that provide more effort than reward? If it is not possible to discontinue these services, ways in which they can be reassigned, restructured, or outsourced to make things easier and more efficient for all should be examined.

Employee Suggestions

Giving employees the opportunity to make their jobs better provides autonomy. Further, morale may increase if they see that positive change is possible. Soliciting ideas from the rank and file for ways that can improve their workflow can be an invaluable method for positive change. If done correctly, suggestions usually will cost little to no money while reducing inefficiency exponentially.

CONCLUSION

Trimming the fat and reducing workplace stress the way businesses do is not overly complicated and does not affect agencies’ ability to serve the public’s need for safety. Rather, they raise morale and bring the scales closer to balance. Adding the goal to every agency of being more efficient takes little effort, yet offers big rewards. Internal agency inefficiency and lack of autonomy are major sources of job stress. For the most part, people have a desire to do a good job and be successful in their careers, but some fall into a negative spiral when their hard work is hindered by inefficiency or supervisory practices that inhibit their efforts.6 Strengthening the paramilitary structure while improving workflow and job satisfaction is not just possible, it is good business practice and can boost agency morale significantly.

Ultimately, workplace morale rests on each individual. Leadership and organizational issues affect this, but when people believe they have a good job, they are satisfied. Helping employees develop that spark for law enforcement as a profession and raising their job satisfaction not only will help their agencies but the communities they serve. Agencies should make it a goal to reduce inefficiency. Supervisors should solicit ideas from the field about how to improve workflow and make things easier for everyone. Restructuring the paramilitary model does not have to involve a change in personnel. It can be accomplished simply by improving workflow and trimming the fat. Raising workplace morale benefits all, and adopting more efficient business practices can help strengthen the paramilitary model if done correctly.

Endnotes

1 Clayton P. Alderfer, Existence, Relatedness, and Growth: Human Needs in Organizational Settings (New York, NY: Free Press, 1972).

2 A.H. Maslow, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” Psychological Review 50, no. 4 (1943): 370-396.

3 National Police Misconduct Statistics and Reporting Project, “2010 Annual Report,” The Cato Institute, http://www.policemisconduct.net/statistics/2010-annual-report/ (accessed August 14, 2013).

4 Morgan Summerfield, “Paramilitary Police Structure and Community Policing: Neither Complimentary Nor Compatible,” http://voices.yahoo.com/paramilitary-police-structure-community-policing-38218.html?cat=37 (accessed August 14, 2013).

5 Ibid.

6 N.F. Iannone and M.P. Iannone, “Supervision of Police Personnel,” in Fundamentals of Law Enforcement Management, edited by Chad C. Legel, Brian J. O'Sullivan, and Fred M. Rafilson (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2005), 3-190.