Perspective

Meeting Individual and Organizational Wellness Needs

By William W. Beersdorf, M.S.

Recently, a lot of attention has focused on the overall health of law enforcement personnel. Topics have included diet; physical fitness; substance abuse; and emotional issues, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide. These certainly represent important areas of wellness.

However, instead of concentrating on each matter individually, I believe it best to promote a more holistic approach to meet the needs of employees. In doing so, individual, as well as agency, wellness should improve, thus serving as protection from the rigors of policing.

Basic Needs

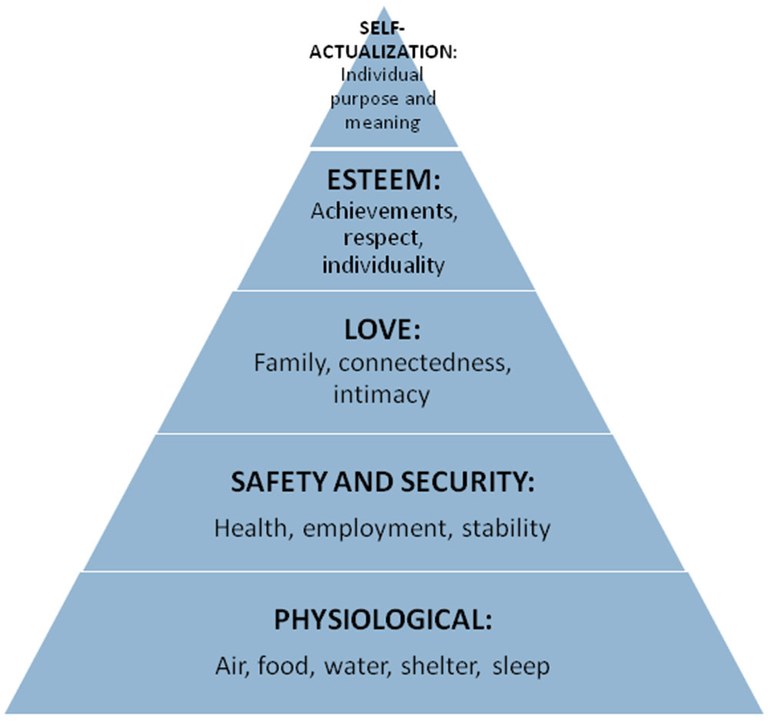

A law enforcement agency, like any other workplace, consists of people with needs. Dr. Abraham Maslow famously used a tiered pyramid to illustrate every person’s hierarchy of such essentials—each level must be met in order, up to the top of the structure.1

Employees require the fulfillment of these needs both personally and professionally. However, law enforcement personnel work in a demanding, high-risk occupation with unique mission requirements and pressures that can make acquiring or sustaining these necessities difficult.

Supervisory Special Agent Beersdorf is an instructor in the Executive Programs Instruction Unit at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia.

During their careers, police professionals face pressure-filled situations; encounter life-threatening scenarios; and endure evil, violence, and death continually. Personnel also may see their colleagues injured or killed in the line of duty and experience problems at home.

Law enforcement employees face additional stressors. Inside the organization, they may deal with long hours and shift work, budget issues, an imperfect judicial system, and lack of support from executive management. Externally, pressures can arise from flawed municipal and legislative bodies, family commitments, and uncooperative or unappreciative members of society.

These combined elements take a heavy toll. Regardless of employees’ resilience, addressing such issues affects their well-being.

Five Pillars of Wellness

Police agencies can enjoy many benefits from establishing an effective wellness strategy.

- Reduction in job-related illness and injury

- Lower workers’ compensation costs

- Decrease in absenteeism and staff turnover

- Improved employee relations

- Healthier work environment

- Enhanced corporate image2

However, most programs have a generic “one size fits all” point of view. I offer a specific model for law enforcement. The Five Pillars of Wellness center on interconnecting dimensions—physical, occupational, social, emotional, and spiritual—important in promoting a culture of employee and agency health.

Physical

Many law enforcement agencies urge physical fitness among employees, with some providing facilities and perhaps work time for exercise. However, they can help personnel in other ways.

Vending machines often sell unhealthy drinks and treats. Instead, departments should provide access to water and wholesome snacks, such as nutrition bars and heart-healthy nuts.

Tobacco use among officers—up to 40 percent—represents another issue.3 Police agencies can help employees who wish to quit. Health insurance providers may offer nicotine replacement products (e.g., patches or gum) and certain medications for free or at a reduced cost. If not, departments can discuss the issue when renegotiating coverage.

Insurance companies provide such treatments because it saves them money in the long run.

In 2006, the state of Massachusetts offered a tobacco cessation benefit to Medicaid enrollees. The benefit provided cessation medications…and up to 16 individual or group counseling sessions…. The smoking rate…fell from 38 to 28 percent over a 2½ year period. [A]nnualized hospitalizations for heart attacks and other acute heart disease diagnoses among…enrollees who used the benefit fell by almost half, and every dollar spent on the benefit was associated with $3.12 in medical savings for cardiovascular conditions.4

Although not all agencies will see such a dramatic result among their employees, they may absorb the insurance company’s savings. Of course, having healthier personnel is the most important benefit.

Medical screenings also prove significant to employees’ health. Law enforcement officers exhibit some the poorest cardiovascular disease profiles and face among the highest risk factors of individuals in any occupation.5 Related issues include hypertension and high cholesterol.

Police departments can coordinate with their insurance carriers to offer screenings for free or at a reduced cost. Or, they could contact a local healthcare provider that offers them as a public service.

Occupational

Typically, law enforcement personnel make a lifelong commitment to their career, seeking personal fulfillment and the opportunity to make a positive impact. However, the policing profession presents continual stress.

Certainly, they enjoy moments of job satisfaction by saving lives and receiving commendations; however, the unique pressures they face can lead to job dissatisfaction, mistrust, and toxicity among employees or in the general work environment.

So, how can police agencies meet the occupational wellness needs of personnel? First, employees need assurance that the department, including executive management, values their work, no matter how mundane. This alone can provide them with the encouragement and motivation needed for the job. Supervisors and administrators can accomplish this by personally commending their personnel.

Former FBI director James Comey stayed up-to-date on important investigations in the agency. Occasionally, he called the case agents to praise them for their work. This became legendary because investigators would joke with the caller who “pretended” to be the FBI director. When Comey convinced them of his identity, the agents became quite apologetic. These phone calls from the director greatly helped motivate these investigators—and their coworkers.

Recognizing employees corporately also proves important. For instance, a monthly or quarterly awards presentation to honor personnel for important investigative work, valor, and case support benefits agency morale.

Social media can serve as a tool to supplement such efforts. Of course, agencies must take this approach carefully and ensure that employees feel comfortable with placement on a site. Police departments can use social media to honor personnel for career milestones and exceptional service. Or, they can share public interest stories highlighting employee actions. By doing so, personnel receive recognition from community members who see positive actions that otherwise may go unnoticed.

Equally important, departments must address the stressors faced by their personnel. Some prove hard to mitigate due to their nature, particularly those involving budget and policy matters. Communication is key. Executive managers must explain the reasons behind such issues. This prevents misunderstandings and fact-twisting rumors from taking hold.

Social

Employees need to establish healthy relationships with family members, friends, and colleagues. They must find a balance between their personal and work lives.

Newly hired personnel easily can become so enamored with their career that they neglect their closest relationships. Many years ago, I had a wife and infant daughter. In addition to working my usual job, I spent another 25 to 30 hours per week as a reserve police officer. So much focus on service and the excitement it brought caused my family to suffer.

A decade later, it happened again with a new spouse and small son when I obtained an investigative position. Handling the most difficult cases and impressing my supervisors seemed important to help me move up the ladder. I worked over 70 hours per week, sometimes more. Finally, my wife gave me an ultimatum—the job or the family. Fortunately, I learned that my employment always would be there. My wife and I have been together for over 28 years now.

Police professionals also can neglect their personal relationships by sitting in the “magic chair.” They experience physiological effects while remaining hypervigilant on the job. Especially over a long period, maintaining such a state of mind has a rebound effect of lethargy after a shift ends. During this recovery period, law enforcement employees often want to sit undisturbed in the magic chair with a beverage and TV remote.6

While in this mind-set, they avoid activities, people, and decisions. This does not necessarily reflect on their attitude; it just indicates the need to recuperate physiologically. Police personnel need to receive training on this phenomenon so they can learn to evade this trap and, instead, focus on developing and cultivating their personal relationships.

Healthy workplace connections hold equal value. Law enforcement professionals must trust each other. They depend on their colleagues when serving warrants, conducting traffic stops, examining crime scenes, and encountering violence. This creates bonds not found among private sector employees.

In addition, police personnel must socialize and have fun with fellow employees. I recall such events as barbeques at officers’ homes and outings with coworkers to the beach or ballgames. These types of activities are relaxing and enjoyable and add depth to friendships made at work.

However, law enforcement employees cannot limit themselves to relationships and hobbies involving only other personnel. Doing so isolates them and narrows their view of persons outside of policing, thus feeding the “us versus them” attitude that may arise among some employees because of the cynical nature of the job.

Someone once told me, “Be wary of a cop who has no friends who are cops or whose friends are only cops.” I always thought this referred to integrity. Now, I see that the statement addresses the needed social balance of law enforcement professionals

“…law enforcement personnel work in a demanding, high-risk occupation with unique mission requirements and pressures….”

Emotional

Police agencies must ensure that the pressures of life inside and outside of the organization do not take an irreversible toll on their employees’ mental well-being.

How do police departments address the emotional health of their personnel? What types of training and services can they offer? Where can law enforcement executives find help when tackling the immediate needs of employees?

Leaders must acknowledge the impact that police work has on law enforcement professionals and offer aid before an emotional crisis occurs. They can take several measures.

- Provide quarterly or annual training to employees and supervisors on how to recognize issues affecting emotional well-being.

- Offer quarterly or annual education for personnel and managers on identifying the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Also, create a plan for how to assist these employees and their families.

- Have preplanned protocols for officer-involved shootings. This could include a quick but thorough review, scenario-based weapon requalification before reentry to duty, or psychological screening.

- Maintain a robust employee assistance program or crisis management system to address needs.

Agencies must assess what plans they have in place. Larger police departments even may employ a psychologist, a luxury that smaller organizations may not enjoy. Regardless, the key is to have a plan in place prior to an employee entering into crisis.

Spiritual

People can embody spirituality without practicing religion. In fact, this concept proves vitally important to employee and organizational health.

Spiritual well-being comprises part of the top tier of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In essence, it means that individuals must know that what they do—on the job and at home—matters and that they make a difference.

However, spirituality holds as much importance for organizations. Morale in a police agency would suffer if employees, as a whole, believed that their service to the public did not hold importance.

Professionally, personnel must recognize their significance to the agency they work for, the people they serve, and the colleagues who function alongside them. When individuals feel valued and believe they make a difference, they reach self-actualization.

This proves important when employees go through a traumatic event or crisis. For example, after involvement in a justified shooting, officers might question themselves, fear judgment, feel guilt, or question their ability to remain on the job. At such a time, executive managers, supervisors, and peers need to encourage these personnel and affirm their value.

Police professionals need to connect with their communities, as well. When they volunteer for activities that aid the public, personnel can foster an attitude of mutual respect.

Conclusion

The Five Pillars of Wellness can help law enforcement employees and organizations find the healthy balance needed to endure the rigors of policing.

Agencies need to ensure that their personnel receive continual training on these dynamics to facilitate overall well-being. Additionally, providing this education to employees’ families can help them fully understand the consequences of police work and, thus, further assist personnel in maintaining a healthy mind, body, and spirit.

Finally, leaders must model the five pillars and achieve employee buy-in to ensure the success of this wellness program.

“Typically, law enforcement personnel make a lifelong commitment to their career, seeking personal fulfillment and the opportunity to make a positive impact.”

Supervisory Special Agent Beersdorf can be reached at wwbeersdorf@fbi.gov.

1 A.H. Maslow, A Theory of Human Motivation (1943; repr., Eastford, CT: Martino Fine Books, 2013).

2 Queensland, Australia, Government, About Employee Wellness: Benefits, accessed August 14, 2018, https://workplaces.healthier.qld.gov.au/public-about/benefits/.

3 “Smoking and Law Enforcement: The Hidden Hazards of Being a Cop,” Tobacco Free Life, accessed August 14, 2018, https://tobaccofreelife.org/resources/smoking-law-enforcement/.

4 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coverage for Tobacco Use Cessation Treatments, accessed August 14, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/quit_smoking/cessation/pdfs/coverage.pdf.

5 W.D. Franke, S.L. Ramey, and M.C. Shelley II, “Relationship Between Cardiovascular Disease Morbidity, Risk Factors, and Stress in a Law Enforcement Cohort,” abstract, Journal for Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44, no. 12 (December 2002): 1182-89, accessed August 14, 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12500462.

6 Kevin M. Gilmartin, Emotional Survival for Law Enforcement: A Guide for Officers and Their Families (Tucson, AZ: E-S Press, 2002).