Analyzing the State of U.S. Policing

By Michael J. Kyle, M.A., Beth Coleman, M.Ed., David R. White, M.J.A., and Joseph A. Schafer, Ph.D.

A recent FBI study proposed that since the occurrence of several high-profile police incidents—especially the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014—law enforcement has sensed a “chill wind.”1 The study suggested that police personnel have felt not only as though “national politicians stood against them but also that the politicians’ words and actions signified that disrespect was acceptable in the aftermath of the Brown shooting.”2

This social movement derives in part from the media’s narrative of police misconduct and wrongdoing, making people feel as though it became socially acceptable to challenge and discredit law enforcement actions. The study asserted that these circumstances have demoralized police officers, causing them to do less—an issue commonly referred to as “de-policing.”3

De-policing has been defined in terms of “dissent shirking,” where not working serves as an emotionally led form of silent protest.4 While this concept comes from broader organizational behavior research, its application to law enforcement—specifically in the post-Ferguson era—holds importance because much of policing involves highly discretionary activities, such as traffic stops, field contacts, and other proactive practices.

Regardless of whether any de-policing effect results from dissent shirking or fear of public scrutiny, if officers become less engaged in proactive duties—including community policing, targeted crime suppression, and investigative inquiries, among other activities—crime may increase.

Scholars have begun to evaluate the possible existence of a post-Ferguson de-policing phenomenon, as well as its potential impact on crime. While a few studies have indicated that the former likely has occurred to some extent, research has produced little evidence regarding the latter.5

A 2017 Pew Research Center study found that 86 percent of surveyed police officers believed that fatal encounters between law enforcement and African American citizens have made policing more difficult. Seventy-two percent reported feeling more reluctant to stop and question people who seemed suspicious.6

Because of a lag in available data for analysis, it proves difficult to determine if a de-policing phenomenon has affected crime rates. However, a National Institute of Justice-sponsored study reported no connections between de-policing and increased violent crime among a sample of large U.S. cities, although the researchers admitted the plausibility of such a connection.7

In addition, while law enforcement agencies historically have found it difficult to recruit minorities, some leaders fear that a “Ferguson effect” might intensify this challenge.

New Research

In 2017, the authors conducted a survey-driven study that allowed law enforcement leaders to report their perceptions of any de-policing within their agencies.8 Additionally, respondents shared whether they had noticed differences in citizens’ behaviors, such as levels of compliance, respect, and cooperation. Leaders also gave their opinions regarding changes in the number of public protests in their jurisdiction as well as variances in applicant pools.9

Participants

The authors administered the survey to students in three sessions of the FBI National Academy (FBINA), a well-established and internationally recognized program that attracts leaders from around the world, although most attendees come from the United States. The respondents included those who worked in or near some of the jurisdictions involved in the high-profile cases, as well as those removed from such incidents and with only vicarious familiarity derived from news outlets, social media, and peer networks.

Combined, total enrollment for the three sessions included 681 law enforcement leaders; of those, 666 agreed to participate in this voluntary research project and complete a survey. Because of the anticipation that any de-policing effect would be most (if not exclusively) prevalent in the United States due to the recent level of public scrutiny, FBINA participants from other nations were excluded from the analysis, leaving a total of 589 respondents.

Mr. Kyle, a former operations commander with the Abilene, Kansas, Police Department, is an assistant professor at Missouri State University in Springfield.

Ms. Coleman is an instructor in the Executive Programs Instruction Unit at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia.

Mr. White, a retired assistant chief from the Paducah, Kentucky, Police Department, is an assistant professor at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan.

Dr. Schafer is a professor of criminology and criminal justice at St. Louis University in St. Louis, Missouri.

Of these law enforcement leaders, 91 percent held the rank of lieutenant or higher—11.7 percent were chief deputies or undersheriffs, and 6.1 percent were chief executives. They were 91.7 percent male and 78.8 percent white, with an average of 21.5 years of service.

Results

Survey respondents considered changes that occurred since January 1, 2014, for reasons other than shifts in budget, staffing, or workforce demands. This helped better capture changes perhaps due to officer discretion.

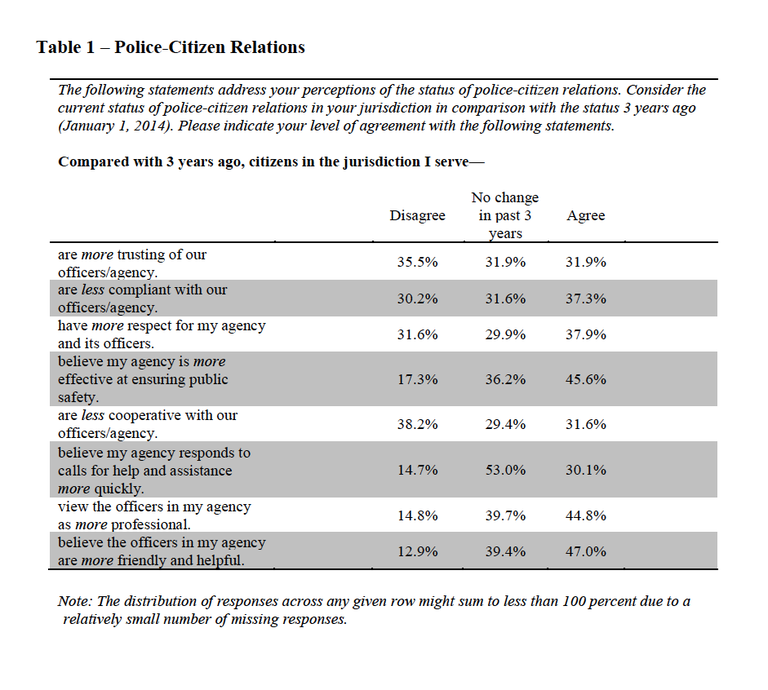

Participants offered a mixed perspective in terms of how they perceived the public’s behavior. More than one-third (37.3 percent) believed that citizens complied less with officers. However, about the same proportion (37.9 percent) reported that civilians had more respect for their agency and its officers, and 38.2 percent disagreed that they were less cooperative.

Nearly half agreed with the statements that citizens in their jurisdiction 1) believed their agency was more effective at ensuring public safety (45.6 percent), 2) viewed officers in their agency as more professional (44.8 percent), and 3) considered officers in their agency more friendly and helpful (47.0 percent), compared with 3 years earlier.

While not reported in Table 1, participants shared their perceptions of overall citizen satisfaction within their jurisdiction, and most (95.6 percent) reported that citizens were either satisfied or very satisfied with their agency.

Although some people believe that a de-policing effect has resulted from dissatisfaction with law enforcement and increased public scrutiny in the wake of the Ferguson incident and other high-profile use-of-force incidents, the survey responses did not reflect negative changes in police-community relations. Most respondents indicated improvement or no change in their jurisdiction, suggesting satisfaction among citizens regarding the agency.

However, dissatisfaction in specific geographic locations (e.g., Ferguson, Baltimore, New York, Chicago, and other cities) where high-profile use-of-force incidents occurred has received national media attention and sparked public outcry across the country. Consequently, officers may feel demoralized and avoid proactive enforcement activities for fear of “becoming the latest YouTube pariah when a viral cell phone video showed them using force against a suspect who had been resisting arrest.”10

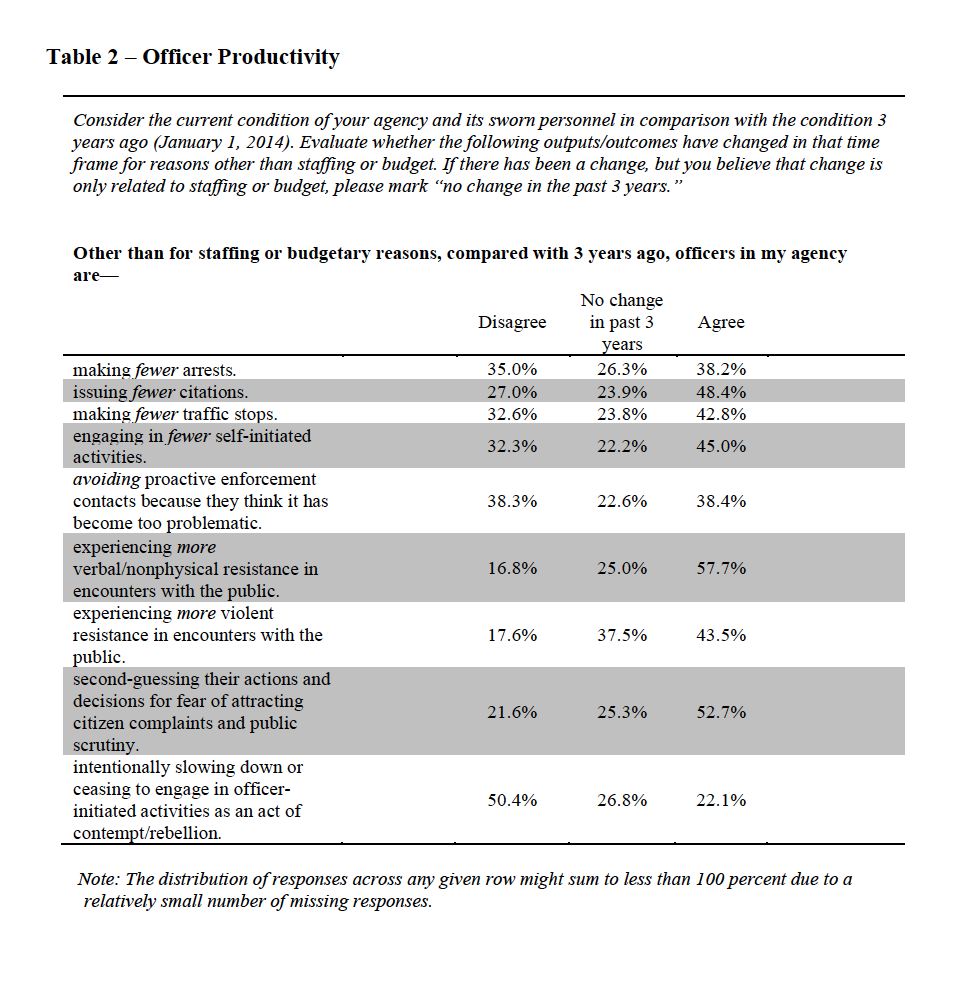

In short, the idea of de-policing due to a Ferguson effect tends to focus more on officer behavior than on citizen perceptions or actions. Table 2 presents respondent assessments regarding officer productivity and the nature of enforcement contacts.

“Survey respondents considered changes that occurred since January 1, 2014, for reasons other than shifts in budget, staffing, or workforce demands.”

In terms of officer productivity, most participants did not report changes in officer-driven outcomes, such as arrests, citations, traffic stops, or other self-initiated activities. However, 38.2 percent did see that officers in their agency made fewer arrests, and 48.4 percent believed that their officers issued fewer citations compared with 3 years prior.

Similarly, 42.8 percent of the respondents perceived that officers in their agency made fewer traffic stops, and 45 percent thought that their officers engaged in fewer self-initiated activities. Roughly equal numbers of respondents (38.3 and 38.4 percent respectively) agreed or disagreed that officers in their agency avoided proactive enforcement contacts because they thought it had become too problematic, while 22.6 percent reported no change. Importantly, only 22.1 percent believed that officers in their agency intentionally hesitated or ceased to engage in officer-initiated activities as an act of contempt or rebellion.

In terms of encountering increased resistance, less than half (43.5 percent) of the respondents perceived a rise in violent resistance, but 57.7 percent thought their officers experienced more verbal resistance from the public. A little more than half (52.7 percent) felt that officers in their agency second-guessed their actions and decisions for fear of attracting citizen complaints and public scrutiny.

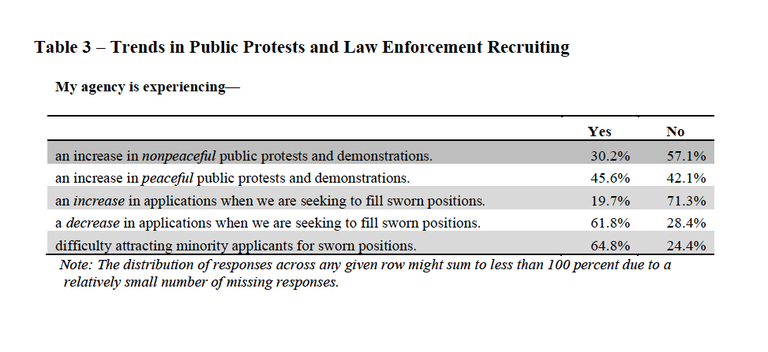

Participants shared their perceptions concerning increases in peaceful and nonpeaceful public protests or demonstrations in their jurisdiction, which might fuel a de-policing phenomenon, and recruiting trends in their jurisdictions, which potentially could result from the increased public scrutiny of law enforcement (see Table 3).

While a notable proportion (44.7 percent) of the respondents believed that peaceful protests had increased, less than one-third (30.2 percent) reported a rise in nonpeaceful protests.

In terms of recruiting for sworn positions, a substantial proportion of the participants indicated that their agency had experienced issues over the past 3 years. Perceptions of a decrease in applications for open sworn positions was reported by 62.6 percent, and difficulty attracting minority applicants for sworn positions in their agency was reported by 64.2 percent of the respondents.

Conclusion

Whether a Ferguson effect exists in U.S. policing remains an open question. The combination of a new capacity to post videos of police use-of-force incidents to social media, the intense coverage of such incidents in both traditional and social media platforms, and the critical public responses of citizens, politicians, and advocacy group leaders may have had a demoralizing impact on law enforcement officers nationwide.

Theoretically, the Ferguson effect manifests in the avoidance of proactive officer-initiated enforcement activities, such as traffic stops; suspicious-person checks; and field interviews, especially with racial minorities, for fear that such encounters may result in a use-of-force incident and, in turn, public scrutiny.

Further, some people have suggested that de-policing holds responsibility for recent increases in violent crime in some U.S. cities. While empirical research has generated no evidence to support this claim, anecdotal evidence suggests that de-policing has occurred to an extent in some jurisdictions. The current study sought the perceptions of law enforcement leaders from agencies of all sizes across the nation concerning this de-policing phenomenon and related trends.

“Collectively, the results of the current study indicated that law enforcement leadership in some jurisdictions faces multiple issues emerging from the perceived legitimacy crisis at the national level.”

While most of these FBI National Academy participants perceived that police-citizen relations in their jurisdiction had stayed the same or improved, of concern is that as many as one-third indicated otherwise.

Although not universal, between one-third and one-half of the leaders saw a decrease in officer productivity. However, these numbers are much lower than the nearly three-quarters of officers who self-reported reduced self-initiated activity in the previously mentioned Pew study.11 Of course, the latter polled patrol officers, while the current study sought the perceptions of ranked employees.

That aside, although not collectively perceived by a clear majority of the respondents, the officer productivity items contained in Table 2 do suggest a view among leaders that some level of de-policing has occurred in at least some jurisdictions. Law enforcement leaders should take note that de-policing—a potential response to the recent negative publicity and increased scrutiny—is likely to further damage police legitimacy.

In terms of improving legitimacy and police-community relations, one often-identified way to overcome the current controversy is to increase racial and ethnic diversity among law enforcement personnel. While most respondents indicated that they perceived smaller applicant pools for sworn positions—problematic in itself—an even greater number of respondents reported that their agencies had difficulty attracting minority applicants. Thus, these findings suggest that improved diversity among police personnel could be difficult to achieve if agencies experience a dwindling number of minority applicants.

Collectively, the results of the current study indicated that law enforcement leadership in some jurisdictions faces multiple issues emerging from the perceived legitimacy crisis at the national level.

Ms. Coleman can be reached at mecoleman@fbi.gov, Mr. Kyle at michaelkyle@missouristate.edu, Mr. White at davidrwhite@ferris.edu, and Dr. Schafer at joseph.schafer@slu.edu.

Endnotes

1 Federal Bureau of Investigation, Office of Partner Engagement, The Assailant Study–Mindsets and Behaviors, accessed April 24, 2019, http://lawofficer.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/MindsetReport.pdf.

2 Ibid, 3.

3 Ibid. For additional information, see Joshua Chanin and Brittany Sheats, “Depolicing as Dissent Shirking: Examining the Effects of Pattern or Practice Misconduct Reform on Police Behavior,” Criminal Justice Review 43, no. 2 (May 2017): 1-22, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0734016817704696.

4 Ibid.

5 For instance, see John A. Shjarback, David C. Pyrooz, Scott E. Wolfe, and Scott H. Decker, “De-policing and Crime in the Wake of Ferguson: Racialized Changes in the Quantity and Quality of Policing Among Missouri Police Departments,” Journal of Criminal Justice 50 (May 2017): 42-52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2017.04.003.

6 Rich Morin, Kim Parker, Renee Stepler, and Andrew Mercer, “Behind the Badge: Amid Protests and Calls for Reform, How Police View Their Jobs, Key Issues and Recent Fatal Encounters Between Blacks and Police,” Pew Research Center, January 11, 2017, accessed April 29, 2019, http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/01/11/behind-the-badge/.

7 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, Documenting and Explaining the 2015 Homicide Rise: Research Directions, Richard Rosenfeld, June 2016, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249895.pdf.

8 This study was a joint effort between the FBI and Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

9 Research based around the measurement of perception always is subject to the limitations of both personal and organizational biases. For additional information on this point, see Michael Brainard, Leadership Pitfalls and Insights into Unconscious Bias (Brainard Strategy, 2016), accessed April 29, 2019, http://www.brainardstrategy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/BrainardStrategy.LeadershipPitfallsAndInsightsIntoUnconsciousBias.pdf.

10 Heather Mac Donald, The War on Cops: How the New Attack on Law and Order Makes Everyone Less Safe (New York, NY: Encounter Books, 2016), 3.

11 Morin, Parker, Stepler, and Mercer.