Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement (Part 1)

By Steve Gladis, Ph.D., Connie Whittaker Dunlop, Ed.D., and Salpi S. Kevorkian, M.S.

Negative press, polarity politics, racial issues, movements to defund the police, and many other issues have conspired to reduce the ranks of law enforcement by ever-increasing, worrisome numbers. The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) released an excellent comprehensive study on this complex and serious crisis and how police agencies are addressing it. Three major talent issues emerged: 1) fewer people are applying; 2) more officers are leaving their departments — and, in many cases, the policing profession — well before retirement age; and 3) a growing number of current officers are becoming retirement eligible.1

This PERF study issued 12 takeaways to improve recruitment and retention, most of which focus on the officer, not the leader. While the study is worthy of every chief’s attention, research on talent retention in business and industry demonstrates clearly that much turnover is due to poor leadership. People leave managers, not jobs.2 And, although the socioeconomic and political reasons for police turnover are many and complex, leadership must be regarded as a critical issue.

The command-and-control leadership model baked into policing culture is generally misaligned with Gen Y and Gen Z. Business leaders have long believed that a “coach approach” to leadership is best for today’s workplace and should be embraced by leaders.3 Two large police agencies in Virginia have taught these techniques to executives and their leadership staffs.4 Other departments may want to embrace coaching as well.

To this end, we offer the three-part “Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement” series, which provides a valid and reliable coaching model for agencies to follow.

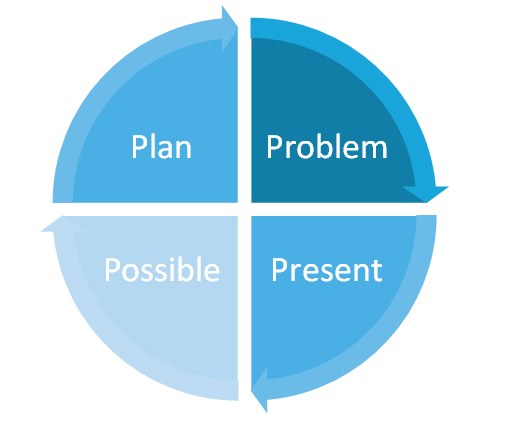

This first article will focus on coaching to solve problems. It will explain the basic steps of the 4P’s Coaching Model: problem, present state, possible future state, and plan.5 Using a realistic composite case study extracted from our experience teaching numerous law enforcement officers, we will demonstrate how effective leaders employ this process by asking questions, not giving commands or advice. While we have found that all generations like this approach, Millennials and Gen Zs, particularly, appreciate its inclusivity.

“Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement” Series

Part 1: Coaching to Solve Problems

Part 2: Coaching to Develop People

Part 3: Coaching Teams to Solve Problems

Coaching to Solve Problems

Lieutenant Simmons serves as day shift commander of a patrol unit in Trent, Virginia. She has 10 patrol officers working for her — all in single-unit patrol cars. Simmons has been a lieutenant for over 5 years and has established a reputation as intelligent, fair, and easy to work with. She collaborates with her peer lieutenant on the night shift.

Because of the talent shortage, the department has gone from three shifts to two. A few officers are unhappy, but Simmons’ unit had to get creative to have sufficient coverage. Simmons treats her shift members like a team because she believes in the power of people to solve difficult problems. In fact, her team came up with the idea of two shifts with an overtime component.

Dr. Gladis, a former FBI supervisory special agent, is a professor, leadership speaker, and author.

Dr. Dunlop develops leaders, teams, and organizations through coaching and training.

Ms. Kevorkian is a doctoral student, a law enforcement researcher, and an executive coach.

4P’s Coaching Model

Step 1: Problem

Employees who have a problem often present its symptoms as the issue. For example: “My boss is a jerk,” “I hate my team,” or “This job sucks.” The coach approach leader will ask questions to reveal the root cause.

“What’s your boss doing that makes you think he’s a jerk?”

“So, what’s going on in the team?”

“Why does your job suck?”

On the other hand, if a leader addresses only symptoms, they end up with a great solution to the wrong problem. Such attempts at problem-solving look like the whack-a-mole game at an amusement park — swiping at symptoms as they pop up, not getting at real causes. For example, simply transferring a bad leader only moves, not solves, the problem.

The key to coaching is to ask questions, not give advice. By interviewing the employee with curiosity, you calm their natural anxiety and invite them to focus on their problem. Besides, all people usually want to do is relate an issue, so they share it. This helps them self-reflect and, many times, solve it themselves. How often have you come home from work and listened to a spouse or partner describe a problem to you? What happened when you started to give advice? Most often, they will say, “I did not ask for your advice. I just wanted you to listen.” So, listen.

Coaching can best be defined as a conversation with a purpose. And one purpose of such a conversation is to solve a problem. To pin down the real issue when a leader sits down with a team member, the conversation might follow these useful questions:

- What is the most important thing for us to discuss today?

- What is an example of the problem?

- Who or what is involved and how?

Finally, the leader should paraphrase the problem for agreement. After stating their understanding of the issue, they should wait until the employee agrees the problem has been summarized correctly before proceeding.

Corporal Jack Stewart has been an exemplary officer on Lieutenant Simmons’ shift. He is esteemed by his peers, well-liked by the business owners in his territory, and great with people in general. Jack is squared away and listens well. However, following the birth of his first child, he has started to show up late for roll calls and has even missed a few. Simmons has called him in to discuss what is going on.

Simmons: “Jack, what’s going on? I’ve noticed you’ve been coming in late or missing some roll calls. That’s not like you.”

Jack: “It’s my commute. We moved further away, across the state line, to be closer to my in-laws, but the morning traffic is killing me and my wife. We’ve been taking my son Sammy to drop-off at 7 a.m. at daycare — the earliest we can — but there’s no guarantee that I can make it to Trent by 8 a.m. The traffic’s so unpredictable.”

They go back and forth. Finally, Simmons summarizes, “So, your move and Sammy’s birth have complicated your commute, mostly because of the day care drop-off. Is that right?” Jack agrees.

Step 2: Present State

Next, the coach approach leader asks questions to determine the impact of the problem on others. When asked to consider these questions, the employee will often identify several people they overlooked until stopping to reflect — one of the key purposes of coaching. Others impacted often include significant others, coworkers, and friends.

Some valuable questions:

- Who else is affected or involved?

- What is the cost of this problem?

- On a scale from 1 (low) to 10 (high), what impact does the problem have on you?

- What are the consequences of staying on the current path, doing nothing?

“[A]lthough the socioeconomic and political reasons for police turnover are many and complex, leadership must be regarded as a critical issue.”

Often, this part of the discussion leads to a realization that the problem is bigger than the employee initially thought.

Lieutenant Simmons: “So, Jack, it’s clear that the day care situation has impacted your commute, and that’s preventing you from getting to work on time. Who else is it affecting?”

Jack: “Hmm, let me think about that … well, for sure, my wife. There isn’t a day that goes by that we don’t argue about the situation. Some days are worse than others.”

Simmons: “Anyone else affected?”

Jack: “Well, when I show up to roll call late, I guess the other officers see me setting a bad example. Even, I suppose, my son Sammy, who sees my wife and me arguing. Never thought about that before now.”

Simmons: “So, Jack, on a scale from 1 to 10, how would you rate this problem?”

Jack: “Wow, let me think a bit … I’d say it’s an 8 or 9.”

Simmons: “So, if it is an 8 or 9, what happens if you don’t address it?”

Jack: “I’m sure it will get worse.”

Simmons: “What does a 10 look like?”

Jack: “I guess a letter of reprimand in my file or maybe worse. Nothing I want, that’s for sure.”

Simmons: “So, let’s get to solving it so that never happens.”

Step 3: Possible Future State

Next, the coach approach leader must determine what the employee most wants in the future. You cannot hit an unseen target. The coach prods the individual to visualize the ideal future state. This portion of the coaching conversation can be fun, as well as frustrating. Sometimes, the employee has locked themselves down and cannot see options. So, the coach might ask them if they want to brainstorm together. This is generally the only time the coach chimes in other than with questions. It is only to help someone who is stuck. But, as soon as the brainstorming is finished, it is back to coaching — asking questions.

Some questions to ask:

- What would the ideal state look like?

- If a miracle happened and things were great, how would that look?

- What do you want to accomplish?

- What are some approaches you envision?

- What actions would you consider?

“Coaching can best be defined as a conversation with a purpose.”

Lieutenant Simmons asks, “Great, so can we brainstorm possibilities about how to get to that place? What might you try?”

“Sure!” Jack says, and they begin to brainstorm. Maybe his in-laws could come down in the morning and help. Perhaps his wife could switch shifts. Or he could go on nights for a while. But finally, Simmons asks a key question: “I’m just curious, how do some of the other officers cope with this same situation with their children?”

Jack thinks and then says they live in Virginia, so they mostly drop them off at a childcare facility about 2 miles from the precinct.

Simmons curiously asks, “Is the day care facility restricted only to Virginia residents?”

Jack: “No.”

Simmons: “What would stop you from doing the same thing?”

Jack thinks and then bursts out, “Nothing! I could drive with Sammy early in the morning and drop him off in plenty of time, then pick him up on the way home.”

Step 4: Plan

Coaching is ultimately about accountability. In most cases, that means to do something different or stop doing something — making a change. After all, insanity is commonly defined as doing the same thing repeatedly while expecting different results. With coaching, the employee agrees with the coach approach leader to be accountable for doing something before they meet again. Conversations in coaching always have a purpose.

Some good questions:

- What will you do?

- When will you do it?

- How will I know you did it?

After Jack’s big revelation, they agree that it’s one solution with real potential. Jack says he will act immediately.

Lieutenant Simmons: “OK, so what will you do, when will you do it, and how will I know?”

Jack: “I’m going to take a ride over there and will text you later today.”

Simmons: “Great.”

Jack gets Sammy on a wait list at the day care center a couple of miles from the precinct. Within a month, Sammy gets into the facility and, immediately, Jack starts making it to work almost 20 minutes ahead of roll call — in time for a second cup of coffee before his shift.

Conclusion

Like in business, law enforcement is in a talent crisis. So, agencies must focus not only on recruitment but also on retention, especially among their highest performing officers. Good leaders tend to retain the greatest people. Remember, the best — those with more options — tend to leave well before others with fewer options and skills.

To protect your agency against such a double whammy — losing the best and retaining those not up to par — start taking a coach approach to leadership. Define the real problem, assess the impact of the present state, brainstorm possible solutions, and develop a plan.

The second article in this series will focus on coaching to develop people, demonstrating how leaders should conduct developmental interviews regularly to help retain high-performing officers.

“[A]gencies must focus not only on recruitment but also on retention, especially among their highest performing officers.”

Dr. Gladis can be reached at sgladis@stevegladisleadershippartners.com, Dr. Dunlop at dr@conniewhittakerdunlop.com, and Ms. Kevorkian at salpi@thekevorkiangroup.miami.

Endnotes

1 The Workforce Crisis, and What Police Agencies Are Doing About It (Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum, 2019), accessed October 31, 2023, https://www.policeforum.org/assets/WorkforceCrisis.pdf.

2 Tom Nolan, “The No. 1 Employee Benefit That No One’s Talking About,” Gallup, accessed October 31, 2023, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/232955/no-employee-benefit-no-one-talking.aspx.

3 Steve Gladis, Leading Well: Becoming a Mindful Leader-Coach (Fairfax, VA: Steve Gladis Leadership Partners, 2017).

4 Prince William County and Fairfax County, Virginia, Police Departments.

5 Gladis.