Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement (Part 2)

By Connie Whittaker Dunlop, Ed.D., Steve Gladis, Ph.D., and Salpi S. Kevorkian, M.S.

This is the second of three articles in the “Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement” series, which provides a valid and reliable coaching model for agencies to follow. The first article focused on coaching individuals to solve problems in real time using the 4P’s Coaching Model.1 It also introduced a generalized case study to demonstrate how an effective leader employs this model to ask questions, not give advice.

To build on the first, this second article extends the 4P’s Coaching Model to another common leadership practice — developing people. This process is illustrated with the continued story of Lieutenant Simmons, who uses developmental coaching as a retention strategy that proves critical for most professions, especially law enforcement.

“Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement” Series

Part 1: Coaching to Solve Problems

Part 2: Coaching to Develop People

Part 3: Coaching Teams to Solve Problems

Coaching to Develop People

Simply put, coaching is a conversation with a purpose. More specifically, developmental coaching involves a conversation between an employee and their manager to promote professional growth. Developmental coaching conversations generally occur outside of the performance feedback cycle and in a relaxed setting, perhaps over lunch or coffee.

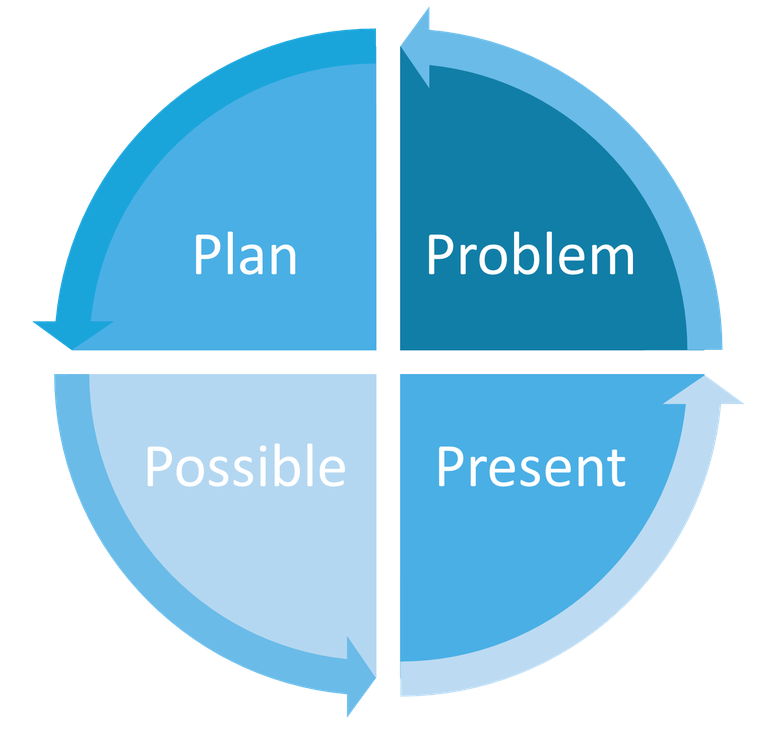

While developmental coaching uses the 4P’s Coaching Model, it reorders the steps. The process involves setting a vision for an officer’s career (possibilities); understanding the officer’s current knowledge, skills, and experience (present state); identifying the gap between the future vision and current state (problem); and developing a set of actions to close that gap (plan).

Developmental coaching starts with possibilities to evoke the positive emotional attractor. According to Intentional Change Theory, sustained change almost always begins with positive emotions and a discussion about what is possible.2

4P’s Coaching Model

Dr. Dunlop develops leaders, teams, and organizations through coaching and training.

Dr. Gladis, a former FBI supervisory special agent, is a professor, leadership speaker, and author.

Ms. Kevorkian is a doctoral student, a law enforcement researcher, and an executive coach.

Lieutenant Simmons, the day shift commander of a patrol unit in Trent, Virginia, supervises a patrol officer named Cindy Lowe.

Cindy is a high performer on Simmons’ squad and has served in the department for 2 years. Well-respected by her peers and community, she has received several outstanding performance awards. Recently, Cindy received a job offer from a neighboring county but declined because of the timing.

Simmons wants to keep Cindy on her squad or at least in the department, so she suggests that they go to lunch one day.

Step 1: Possible Future State

Developmental coaching conversations begin with appreciation for an employee’s contributions and continue with setting a vision for their career’s future state. One expert believes that people should consider the environment they want to work in, activities they want to focus on, and people they want to interact with, among other things. With the rapid pace of change, he suggests that employees envision themselves at work two or three years — not five or 10 — from now.3

To help employees uncover their vision for their careers, managers ask questions like:

- What is next for your career?

- What is your ideal job?

- Where might you be working?

- Who might you be working with?

As Lieutenant Simmons and Cindy sit down at the restaurant, Simmons says, “I just want to tell you how much I appreciate all you do for the squad, the department, and the community. You’re a truly outstanding police officer.”

Cindy is almost speechless and says, “I don’t know what to say except thanks!”

Over lunch, the two talk about what’s next for Cindy.

Simmons asks, “So Cindy, what do you want to be doing in the next year or two?”

Cindy says, “I’m not sure, but I know that I want to be doing more than I am right now. Honestly, I feel a bit stagnant. I do know that I really like working with kids in our community.”

Step 2: Present State

Next, the developmental coaching conversation moves toward understanding the current state of the employee’s career. To help in this, employees find it useful to generate an inventory of knowledge, skills, and experiences. This includes what they know, such as criminal law and traffic regulations; abilities they have, such as communication and investigation; and what they have done, such as three years in law enforcement and graduation from a training academy.

In building this inventory, managers ask their employees such questions as:

- What are you doing when you are at your best?

- What are your strengths? Opportunities for growth?

- What knowledge or skills do you have that differentiate you from others?

Cindy continues, “I always look forward to the days that I spend on school property and with school resource officers (SRO) throughout the community.”

Lieutenant Simmons asks Cindy to tell her more about her work with SROs.

Cindy shares stories about her interactions with kids at school and the difference she felt she made in their lives. In one case, Cindy supported the SRO in a special investigation of a missing teen and was quick to locate and return the juvenile to his family.

Simmons asks Cindy about her stand-out strengths.

Cindy responds, “I’m not sure. I’ve been told that I’m really good in the classroom. I’ve heard that I can take a somewhat boring topic, like drug awareness, and make it interesting for students.”

Simmons asks how Cindy takes a dull topic and makes it interesting.

Cindy reflects, “Well, I tend to tell lots of stories when I teach. I also use high-profile cases as examples. And I get the kids to role-play. Some of them really get into it.”

Step 3: Problem

Then, the developmental coaching conversation addresses the problem — the gap between the officer’s possible future state and the present state of their career. Gaps can exist in an employee’s experience, skills, and/or network.

To identify and address the gap, officers can benefit from answering such questions as:

- What is the gap between where you are and where you want to be?

- What will help you close the gap?

- Who can help you close this gap?

Lieutenant Simmons is really impressed with Cindy’s stories about working with kids. She asks if Cindy would like to serve as a full-time SRO at one of the county’s public high schools.

Cindy says, “No. I like working with kids, but I don’t want that to be all I do. I need variety in my job.”

Simmons says, “I see.”

Cindy continues, “I’d like to find more part-time opportunities in the department to spend time with kids. The best opportunities would place me out in the community and give me a chance to work with teenagers. The problem is that I don’t know what’s out there.”

Simmons responds, “Well, I do. I know what’s out there, and one program might be exactly what you’re looking for.”

“Developmental coaching conversations begin with appreciation for an employee’s contributions and continue with setting a vision for their career’s future state.”

Step 4: Plan

Finally, the developmental coaching conversation closes with a plan — a set of actions that the manager and employee determine together to close the gap between the future and current states of the officer’s career. The best action plans are simple and shared. Research suggests that when you share your goals with someone you perceive to be of higher status, you more likely will achieve them.4

When developing the action plan, managers tend to ask their employees the following questions:

- What will you do now?

- When will you do it?

- How will I know you have done it?

- How can I help?

Lieutenant Simmons asks Cindy if she has heard of a nationwide program called Police Explorers. The county currently works with about 20 kids ages 14 to 20 who are interested in police work. Participating kids take tours of jails, courts, and other criminal justice facilities; do ridealongs with patrol officers; and work on projects to help expose them to the nuances of police work.

Cindy mentions that she knows two officers involved in the program.

Simmons offers to make an introduction to Sergeant O’Leary, who runs the program. “I’m sure he’d be happy to talk with you. He’s always looking for officers to work with the kids. And you know that I would highly recommend you. Would that be a good first step?”

Cindy agrees.

Simmons asks, “Anything else that might help you explore this?”

Cindy responds, “I guess I could start doing some reading and researching on the Internet, along with interviewing officers I know who have worked with the Explorers.”

Simmons says, “Sounds great, and I’m sure Sergeant O’Leary can give you a bunch more names.”

About that time, the waiter left the check. Cindy reaches for her wallet to split it, but Simmons says, “No dice, this is my treat.”

Driving back to the station, Simmons summarized next steps: “I’ll talk to Sergeant O’Leary this week and let you know when to call him. You work on the research, and then let’s get coffee in a month. Sound about right?”

“You bet. I can’t tell you how grateful I am.”

“Me too — that you’re on the squad.”

Later, Cindy talks with O’Leary, who gives her some information on the Explorer program and the names of several officers involved. She interviews three of them and learns a lot about the opportunity but decides to start a cohort Master’s in Public Administration program at a local university with the support of Simmons. Eventually, Cindy does work with the Explorer program, gets her MPA, and is promoted.

Conclusion

This article has detailed the developmental coaching process using the 4P’s Coaching Model and illustrated it with the continuing story of Lieutenant Simmons. It has also provided sample questions for each phase of the coaching process that you can implement in your agency today. Developmental coaching is one important way to face law enforcement’s talent crisis head-on.

The third and final article of this series will focus on another method — coaching teams.

“The developmental coaching conversation closes with a plan — a set of actions that the manager and employee determine together to close the gap between the future and current states of the officer’s career.”

Dr. Dunlop can be reached at dr@conniewhittakerdunlop.com, Dr. Gladis at sgladis@stevegladisleadershippartners.com, and Ms. Kevorkian at salpi@thekevorkiangroup.miami.

Endnotes

1 Steve Gladis, Connie Whittaker Dunlop, and Salpi S. Kevorkian, “Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement (Part 1),” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, November 7, 2023, https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/facing-the-talent-crisis-in-law-enforcement-part-1; and Steve Gladis, Leading Well: Becoming a Mindful Leader-Coach (Fairfax, VA: Steve Gladis Leadership Partners, 2017).

2 Richard Boyatzis, Melvin L. Smith, and Ellen Van Oosten, Helping People Change: Coaching with Compassion for Lifelong Learning and Growth (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2010).

3 Timothy Butler, Getting Unstuck: How Dead Ends Become New Paths (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2007).

4 Jeff Grabmeier, “Share Your Goals — But Be Careful Whom You Tell,” Ohio State News, September 3, 2019, https://news.osu.edu/share-your-goals--but-be-careful-whom-you-tell/.