Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement (Part 3)

Salpi S. Kevorkian, M.S., Steve Gladis, Ph.D., Connie Whittaker Dunlop, Ed.D.

This is the third of three articles in the “Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement” series, which offers a valid and reliable coaching model for agencies to follow. The previous two articles discussed other strategies for addressing this talent crisis by using one-on-one conversations that involve asking questions to solve problems (Part 1) and posing questions to develop people on teams (Part 2).1 But, what if a more challenging and urgent issue arises that requires multiple law enforcement personnel with various ranks, experiences, and expertise to envision and chart a path forward?

In this article, we will discuss how to use the 4P’s Coaching Model2 with teams to solve problems. To illustrate this process, we will continue with the story of Lieutenant Simmons, who, in this case, needs to tackle a hard-to-solve recruitment and retention issue faced by her agency.

“Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement” Series

Part 1: Coaching to Solve Problems

Part 2: Coaching to Develop People

Part 3: Coaching Teams to Solve Problems

Coaching Teams to Solve Problems

In the past 6 months, a police department in Trent, Virginia, has lost not only veteran officers through retirements but also younger officers who have opted to find new careers — a phenomenon common to many other agencies around the country. Lieutenant Simmons’ squad has lost one younger officer, and she wants to do something about the departures.

Simmons talks to the chief and decides to gather a couple of younger and older officers from various shifts and use them as a problem-solving team that will employ a technique called “action learning” to solve the issue.

Embracing Action Learning

Action learning is a transformational process that involves a team’s engagement to solve complex problems while learning individually and as a group.3 It has been developed and adapted across industries and sectors over the years. This process yields more than just finding solutions — it promotes and facilitates learning, cultivates critical problem-solving skills, fosters team member engagement and trust, increases motivation, and builds effective teams.4

These practices resemble those that first responders use on scene — they often involve a series of questions aimed at better understanding a situation to inform the best possible action to take. The individual leading the action learning process (i.e., the designated coach) assumes the role of a “traffic cop.” The traffic cop does not directly participate in the problem-solving component but guides the conversation to make sure it is going in the right direction by asking powerful and impactful questions, issuing stops, or intervening as needed to augment the discussion.

Ms. Kevorkian is a doctoral student, a law enforcement researcher, and an executive coach

Dr. Gladis, a former FBI supervisory special agent, is a professor, leadership speaker, and author.

Dr. Dunlop develops leaders, teams, and organizations through coaching and training.

The goal of participation in action learning centers on active listening, reflection, mirroring, and learning via direct and open-ended inquiry. This process encompasses a team-oriented coaching approach in learning how to solve problems collaboratively and build synergy within teams. Participants consist of:

- the traffic cop (coach/facilitator), who manages the timing, rules, and flow of the discussion;

- the appointed spokesperson, or problem presenter, who introduces the challenge or issue at hand; and

- a group of active listeners and questioners who engage in back-and-forth dialogue to uncover the solution to the problem and achieve an actionable plan to get there.

Lieutenant Simmons calls the meeting to order: “Thanks so much for taking the time to address this staffing/talent problem that’s affecting departments around the country. We’ll be working together every couple of weeks for a couple of hours for several months or so to explore this issue and give some recommendations to the chief. He wants an initial report in 90 days.”

Simmons then explains how the action learning problem-solving protocol works by using questions in a group setting, not only to solve problems but also to learn how to be better listeners and leaders by using coaching (asking powerful questions) as the approach.

She explains that there are only a couple of rules: “You can only ask questions. No gratuitous speeches or advice unless asked for by the problem presenter.”

As the coach, Simmons controls the flow and stops or starts, coaching as she sees fit. Simmons is the traffic cop, so to speak.

Using the 4Ps Coaching Model

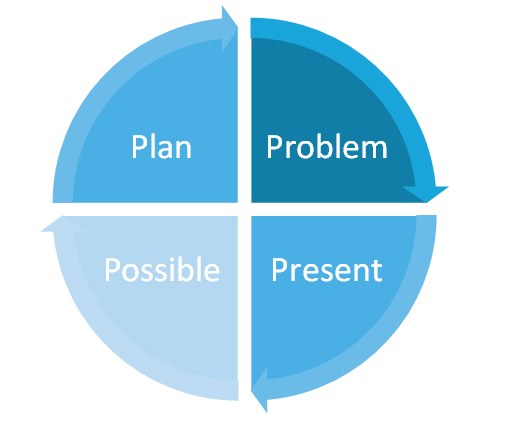

Different from the last article (Part 2), which focused on developing people, this article on coaching teams uses action learning to work through the 4P’s in a different order. This process involves: diagnosing the overarching issue or challenge (problem); identifying details and the impact of this problem on the individual and any other persons involved (present state); determining the best attainable future based on the desired outcome (possible future state); and developing a future-looking strategy to achieve this state (plan).

“The goal of participation in action learning centers on active listening, reflection, mirroring, and learning via direct and open-ended inquiry.”

4P’s Coaching Model

Step 1: Problem

In this step, the goal is to identify the heart of the matter (i.e., the most important problem) to set the stage for action learning to occur. The appointed spokesperson, or problem presenter, clearly, briefly, and concisely — no more than a couple of minutes — shares a summarization of the urgent, complex issue with the team. Then, the floor opens to the group for powerful and impactful back-and-forth questions and responses to gain more clarity and insight on the problem to be solved.

Lieutenant Simmons says, “I’ve asked Jake Leonard to be the problem presenter today, even though we all own this talent retention issue. Go ahead, Jake.”

“As you all know, we’ve lost 20% of our department in the last two years through retirement and attrition. That’s affecting shiftwork, imposing mandatory overtime, you name it. We must figure it out or continue to work with an anemic staff.”

Simmons responds: “Ok, thanks Jake. Now, who has the first question?”

Larry, an older officer, asks, “What are the stats by rank of who’s leaving?”

Simmons pulls out a stat sheet that shows mostly Gen X and Baby Boomer officers leaving, but, ironically, officers with less than five years on the job are leaving as well.

Step 2: Present State

Here, the goal is to frame the problem identified in the last stage and understand its context for better problem-solving. Team members support and challenge one another while breaking down a complex problem to bring it into focus. The coach, or traffic cop, poses questions related to who cares, why it matters, whom and what the problem affects, and the possible consequences of not finding a good solution.

Questions go back and forth as the group establishes the size and scope of the problem by asking questions of not only Jake but also themselves.

With this newfound insight, Lieutenant Simmons jumps in at a good stopping point in the conversation to recap what was said:

“OK, great discussion. We’ve got a real problem here that’s impacting all of us. We’re losing officers at the speed of light, and if we don’t do anything about it, we are running the risk of falling even further behind. So, if you had to rate this problem from 0 (no effect on you) to 10 (worst possible effect on you), how would you rate it?

Right away, Detective Costello quips: “We don’t have the juice to make these kinds of decisions, but it’s clearly impacting my ability to do my job! A 10!”

Others, including higher and lower ranking officers, chime in and agree with him.

And through “the wisdom of crowds,” they determine this problem threatens the department existentially.

Step 3: Possible Future State

Throughout this step, the coach poses a series of questions to the group to identify the best possible future state, based on the desired outcome, and determine the most effective actionable ideas to reach it. The team brainstorms and chooses the best ideas to solve the core problem at hand, using creative strategies for learning and exploring new possibilities, strategies, and information that can be used for problem-solving.

After hearing both the problem and the chilling present state, including some of the frustrations of the group, Lieutenant Simmons asks, “So, who would like to ask some questions about the future possibilities?”

“What do you mean?” asks Joe, a corporal.

“Well, if a miracle happened and we solved the talent issue, what would the department look like?”

Edgar, a junior officer, spoke up: “We’d still have Chuck, Stan, and Morgan on the force, and we’d have excellent candidates waiting in line to get into the academy.”

Simmons then asks, “Great image, so how do we do that? What will we need to do that? What’s our plan? How about everyone writes down three to four suggestions that the department could follow within the next two weeks. Then, maybe we could rank those suggestions today.”

Simmons gave them about five minutes to think and write down suggestions on yellow sticky notes. Then, they put them up on a flip chart labeled “suggested actions.” Next, Simmons had them each rank their preferences on another sticky note and then vote on their top choices:

- Talk to the International Association of Chiefs of Police about their research and best practices

- Find out what the Police Executive Research Forum has discovered

- Interview the head of the Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police

Step 4: Plan

This step focuses on creating a forward-looking, strategic action plan based on the learning that occurred during the session. The coach facilitates the creation of a time-bound, actionable plan for the team to achieve the best possible state. Team members decide on strategies and norms moving forward to ensure accountability, set milestones, ensure that progress toward goals is met, and measure success in implementing the identified solution.

Lieutenant Simmons said “great” and asked the team for several volunteers to head up an inquiry into each of these key suggestions. She asked the members to work in groups of two. Simmons got them to agree on a meeting every two weeks for each pair to report back on their progress and what they learned. Each group set a goal for the next meeting. Simmons thanked them, and the meeting was adjourned.

“Team members decide on strategies and norms moving forward to ensure accountability, set milestones, ensure that progress toward goals is met, and measure success in implementing the identified solution.”

For the next three months, the eclectic team of young and older officers worked on the talent project diligently under Simmons and continued to meet after the 90-day report was submitted.

They had great sessions, always out of respect and curiosity, and used action learning to get the job done. Their initial report was a plan to plan, setting out future goals and objectives for the “talent team,” as they now called themselves. Suddenly, morale was better than it had been for years within the department. Other agencies started to call them for advice.

Within a matter of months, recruitment numbers started to spike, and existing officers reported feeling more confident and capable and that they mattered at their jobs.

Conclusion

Action learning promotes both team and leadership development. Using action learning in tandem with the 4P’s Coaching Model can help revolutionize the current approach to the talent crisis by beginning with powerful, forward-looking, and solution-oriented change within law enforcement agencies. Not only is this process beneficial for problem-solving and learning but it also pays dividends by inspiring effective teamwork and communication. It can also play a critical role in retention, fostering trust and ensuring officers feel heard and valued by their leaders.

The team-coach approach process is low-cost and low-burden to implement, and it can also immediately be put into use by police leadership.

This concludes the “Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement” series, which offers effective coach-approach leadership styles to use in different scenarios. While leadership coaching is not a panacea for the personnel issues facing agencies, it has largely been overlooked as an effective tool. Corporations have embraced this approach with gusto — so should law enforcement.

“Action learning promotes both team and leadership development.”

Ms. Kevorkian can be reached at salpi@thekevorkiangroup.miami, Dr. Gladis at sgladis@stevegladisleadershippartners.com, and Dr. Dunlop at dr@conniewhittakerdunlop.com.

Endnotes

1 Steve Gladis, Connie Whittaker Dunlop, and Salpi S. Kevorkian, “Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement (Part 1), FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, November 7, 2023, https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/facing-the-talent-crisis-in-law-enforcement-part-1; and Connie Whittaker Dunlop, Steve Gladis, and Salpi S. Kevorkian, “Facing the Talent Crisis in Law Enforcement (Part 2), FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, December 5, 2023, https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/facing-the-talent-crisis-in-law-enforcement-part-2.

2 Steve Gladis, Leading Well: Becoming a Mindful Leader-Coach (Fairfax, VA: Steve Gladis Leadership Partners, 2017).

3 Dr. Reginald Revans originally developed this series of techniques. Revans’ Law states that for an organization to survive, its rate of learning must equal or exceed the rate of change in its external environment. For additional information, see “Reg Revans,” Action Learning Associates, accessed January 2, 2024, https://www.actionlearningassociates.co.uk/action-learning/reg-revans/.

4 Michel J. Marquardt, Optimizing the Power of Action Learning: Real-Time Strategies for Developing Leaders, Building Teams, and Transforming Organizations, 3rd ed. (Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2018).